THE END of America’s election season always coincides with Halloween. That can make for some deeply weird campaigning. Democrats in Las Vegas, Nevada, staged a “Project 2025 haunted house” by decorating their offices with skeletons, tombstones—and a video of January 6th 2021. A huge, fuzzy stuffed spider hangs in a web in one corner. “Look what a mess Trump has made”, a poster in front of it reads, “in his web of LIES!” A cardboard cutout of Kamala Harris (wearing a cape) stands watch over the coffee bar, where exhausted campaign staffers nurse their 6pm brews.

With just six electoral votes, Nevada is the least populous of the seven swing states. It has been the friendliest terrain for Democrats in recent elections. Every other swing state went for Donald Trump in 2016, but the last Republican presidential candidate to win in Nevada was George Bush in 2004. Yet the margin of victory for Democrats is always narrow. Joe Biden won the Silver State by just over two percentage points in 2020. As of November 2nd, The Economist’s presidential-forecast model suggests that Nevada is a toss-up. Democrats are losing ground nationally with Latino and working-class voters, who make up significant parts of Nevada’s electorate. But the party’s ground game in Nevada is strong, thanks in large part to the endurance of the political machine built by the late Harry Reid, a former majority leader in the Senate. Can Democrats eke out another win?

Because Nevada’s population is small and centralised, its political geography is easy to understand. There are three regions, electorally speaking, that matter in Nevada: Clark County, Washoe County and the rural parts of the state. Nearly three-quarters of Nevada’s 2.4m registered voters live in Clark County, which includes Las Vegas. These voters lean Democratic. Rural counties—with about 12% of voters—are heavily Republican. And Washoe County, which includes Reno, is swingy. Slightly more Republicans than Democrats live there, but the area has tended to back Democratic presidential candidates and senators in recent years.

In past elections Democrats have been able to run up the vote enough in Las Vegas and its suburbs to offset the Republican Party’s advantage in rural areas. But according to early-voting numbers, that large lead in Clark County has yet to materialise. In fact, Republican early turnout has surged. “Usually it’s been the Democrats who have [early voting] all to their own, and then the Republicans have had to try to play catch-up on election day,” says David Damore, a political-science professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “Now it’s a little bit reversed.”

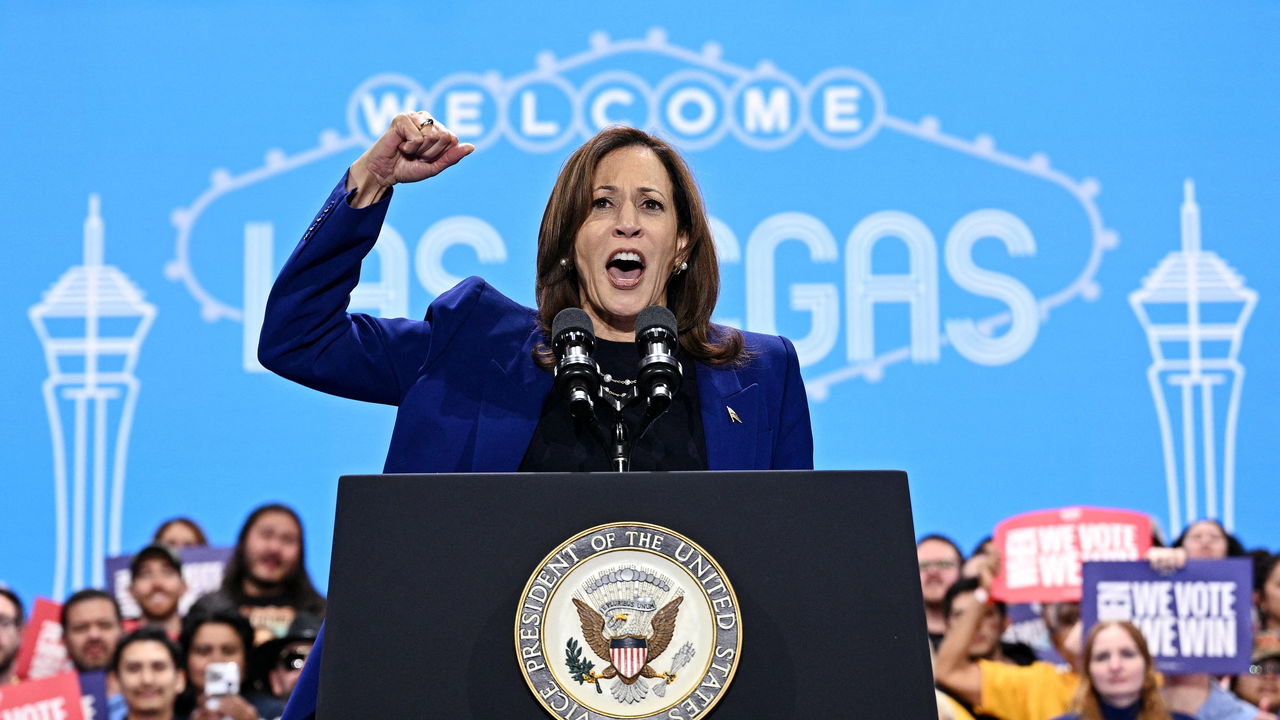

Democrats are trying to stay zen. Campaign operatives suggest that mailed ballots, rather than in-person early voting, take longer to arrive and be processed. Their big lead in Clark County is coming, they argue, and the ground game doesn’t need tweaking. Not everyone is so diplomatic. “The Republicans are kicking our ass at the early voting,” exclaimed Dina Titus, a Democratic congresswoman, at a rally for Ms Harris in North Las Vegas on Halloween night. “We cannot let that happen.”

Three questions haunt the early-voting figures, and will determine whether Ms Harris or Mr Trump can claim victory in Nevada this year. The first is whether non-partisans will break for Democrats or Republicans. In 2020 the state began to automatically register Nevadans to vote when they apply for a driver’s licence. This swelled the voter rolls with non-partisans, the default choice. Unaffiliated voters jumped from a quarter of Nevada’s registered voters in 2020 to a third in 2024, and could swing the election for either candidate. Shelby Wiltz, who runs the co-ordinated campaign for Nevada Democrats, insists that the state party’s network and the Harris campaign were built to reach these voters, which skew younger than members of both major parties.

The second question is whether many Republicans will defect. In recent weeks Ms Harris’s campaign has been courting conservatives who cannot bring themselves to vote for Mr Trump. Vanessa Herbin, a 65-year-old Las Vegas resident, had never been to a political rally before arriving at Ms Harris’s gathering on Thursday evening. Supporters swayed to Maná, a Mexican rock band, and shivered in the cool desert night. Mrs Herbin has long voted for Democrats, but says her husband is a registered Republican who is also supporting the vice-president. That’s not the kind of thing that shows up in early-voting data.

Finally, it is unclear whether the Republicans voting early are new and low-propensity voters, who usually sit out elections but were inspired to go to the polls. Or if, at Mr Trump’s urging, Republicans are just voting early instead of on election day. Democrats have taken to calling this the “cannibalisation” of election-day votes. If the former is true, Ms Harris is in deep trouble and Jacky Rosen, a Democratic senator running for re-election, may have a closer race on her hands than polls suggest. If the latter proves to be correct, then the race will still be tight but Ms Harris could be saved by those slow postal votes in Clark County after all. Halloween may be over, but Nevadans are still in for a scare. ■

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Blog Post1 week ago

Blog Post1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago