Where in the unholy heck did all these bees come from?!

Personal Finance

Wait, does America suddenly have a record number of bees?

Published

1 year agoon

We’ve added almost a million bee colonies in the past five years. We now have 3.8 million, the census shows. Since 2007, the first census after alarming bee die-offs began in 2006, the honeybee has been the fastest-growing livestock segment in the country! And that doesn’t count feral honeybees, which may outnumber their captive cousins several times over.

This prompted so many questions. Does this mean the insect apocalypse is over? Are pollinators saved? Did we unravel the web of maladies known as colony collapse disorder?

But let’s start with the most important question: Is there, in fact, a bee boom?

We consider the census from the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) to be the gold standard, but another data set from those quantitative crusaders, the annual honey report, actually shows bee colonies losing ground.

Agriculture Department economist Stan Daberkow, who helped write the definitive comparison of these sources, retired in 2008 but continues to follow the beekeeping business closely. When we tracked him down, he dove headfirst into our data mystery, sending us theories and exchanging emails at 1:35 a.m. and beyond.

Like any source produced by humans and constrained by budgets, Daberkow said, the honey report and Census of Agriculture have their limitations. The honey report focuses on operations with five or more hives, while the census includes every farm in the country. In this case, “farm” means any plot of land that sells at least $1,000 of agriculture products in a year, a measure that could include more hobbyists and dabblers in the buzz biz.

Inflation also increases the share of beekeepers who qualify for the census: The Agriculture Department’s $1,000 farm definition hasn’t changed since 1975. So as honey prices, pollination fees, hive prices and other sources of bee revenue rise, more hobbyists will magically transmogrify into “farmers.” Some of those new farmers, plus others discovered through census outreach efforts, might get added to the honey report. So next year’s honey report could paint a sunnier picture.

Daberkow said he was somewhat “leery” of the latest census data. Given less-than-ideal recent honey prices, major producers shouldn’t have much incentive to expand their operations. “Any growth would likely have come in smaller operations, a demographic USDA goes to great lengths to track down for the census,” he said.

Sure enough, the census shows the number of operations with any bee colonies has ascended far faster than honey production or bee-colony counts — about 160 percent since 2007.

Much of the explosion of small producers came in just one state: Texas. The Lone Star State has gone from having the sixth-most bee operations in the country to being so far ahead of anyone else that it out-bees the bottom 21 states combined.

Our data showed the biggest increases in north Texas, a region not traditionally considered a honey hotbed. So we started dialing beekeepers to ask what was going on. The first thing we learned? Our job would be half as hard and twice as joyful if all our sources were Texas bee boosters. Every last one seemed genuinely thrilled to pick up the phone.

Consider John Talbert of Sabine Creek Honey Farm, age 85. A past president of both the Association for Facilities Engineering and the Texas Beekeepers Association, Talbert takes a spoonful of honey before bed each night and brings a jar of wildflower honey to every politician he meets. He does the same for his doctor and his dentist.

“That’s so small that it couldn’t be considered a bribe,” Talbert told us. “It’s just a gesture of good faith!”

Talbert is such an infectious evangelist, we suspect that he and his many protégés could have propelled the great American bee resurgence by enthusiasm alone. But the Texas beekeepers all pointed to one clear reason for the bee boom — and that reason answered the phone on our second try.

Dennis Herbert wouldn’t strike you as a political mover and shaker. A retired wildlife biologist, Herbert, 75, boasts of no fancy connections and drops no names. But in 2011, after keeping bees for a few years, he went to the Texas legislature and laid out a simple hypothetical.

“You own 200 acres on the other side of the fence from me, and you raise cotton for a living. You get your ag valuation and cheaper taxes on your property. I have 10 acres on the other side of the fence and raise bees, and I don’t receive my ag valuation. And yet my bees are flying across the fence and pollinating your crops and making a living for you,” Herbert said. “Well, I just never thought that quite fair.”

In 2012, the Herbert Hypothetical gave rise to a new law: Your plot of five to 20 acres now qualifies for agriculture tax breaks if you keep bees on it for five years.

Over the next few years, all 254 Texas counties adopted bee rules requiring, for example, six hives on five acres plus another hive for every 2.5 acres beyond that to qualify for the tax break. Herbert keeps a spreadsheet of the regulations and drives across the state to educate bee-curious landowners.

Herbert himself doesn’t qualify for the exemption. His modest homestead in the tiny town of Salado, about an hour north of Austin, isn’t big enough. But, he says, “more bees provide more pollination, and so I get to eat a little better. I get my watermelon during the summer. And that doesn’t make me anybody special at all. I just, I like my watermelon.”

While Herbert never intended it, Texas bee exemptions have become big business. That has created an opportunity for Gary Barber, a former newspaper photographer.

Barber got bit by the bee bug after he left the Dallas Morning News in 2014. His firm, Honey Bees Unlimited, now leases and runs 1,500 hives for 170 clients in eight counties north of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. As developers split the once-rural countryside into five- and 10-acre ranchettes, he’s signing up new clients faster than he can split hives to place on their land.

“It’s crazy, the blanket of bees over these counties!” Barber said. “Honestly, it’s not bee country: You’re not going to make it like a traditional beekeeper. But it’s really great because … now we’ve got pollinators all around!”

Barber has risen to become vice president of the Texas Beekeepers Association and promotes the industry alongside Herbert — especially every other year when the Texas legislature is in session.

“There’s usually some legislator that wants to mess with [the tax break], and we’ve got to go tell them why it’s great,” Barber told us. “And luckily, while our two political parties don’t agree on much, they all seem to want to save bees.”

These Texans helped explain the rise in beekeeping operations. And they built our trust in the Census of Agriculture as a purveyor of weird truth. But even with its army of small producers, Texas still ranks only sixth in the number of actual bee colonies. To find the true core of the bee boom, we had to make like the Village People and go west.

When the census was taken in December 2022, California had more than four times as many bees as any other state. We emailed pollination expert Brittney Goodrich at the University of California at Davis, who explained that pollinating the California almond crop “demands most of the honeybee colonies in the U.S. each year.”

Every February and March, something like 170 million almond trees unite in one of Earth’s great synchronized acts of sexual reproduction — made possible by the migration of the bees.

Pollination — not honey prices — has been the true rocket booster strapped to the back of the modern beekeeping industry. And almond pollination is responsible for $4 of every $5 spent on bee fertility assistance in the United States, according to NASS.

America’s almond acreage has more than doubled since 2007 as the world’s food firms race to stuff the nut into every conceivable granola mix, nut butter and milk substitute. So it seems reasonable to assume the honeybee population doubled along with it. After all, those almonds aren’t pollinating themselves.

(Editor’s note: Some of those almonds are, in fact, pollinating themselves. But self-pollinating trees remain a small minority.)

So the situation on the ground seems to confirm the census: We probably do have a record number of honeybees.

Sadly, however, this does not mean we’ve defeated colony collapse. One major citizen-science project found that beekeepers lost almost half of their colonies in the year ending in April 2023, the second-highest loss rate on record.

For now, we’re making up for it with aggressive management. The Texans told us that they were splitting their hives more often, replacing queens as often as every year and churning out bee colonies faster than the mites, fungi and diseases can take them down.

But this may not be good news for bees in general.

“It is absolutely not a good thing for native pollinators,” said Eliza Grames, an entomologist at Binghamton University, who noted that domesticated honeybees are a threat to North America’s 4,000 native bee species, about 40 percent of which are vulnerable to extinction.

Grames helps lead EntoGEM, a collaborative effort to sift through more than 120,000 often-obscure scholarly articles worldwide in search of hidden insect-population data. Grames said the consensus holds that pollinators, like all insects, are in decline — losing probably 1 to 2 percent a year.

(“Pollinators” is not a synonym for “bees,” by the way. Legions of insects have evolved to help native plants with long-distance reproduction, including butterflies, moths, beetles, flies, midges and gnats. Many aren’t even fully known to science, so we can’t say with certainty they’re declining. But optimism would seem misplaced.)

Many of the same forces collapsing managed beehives also decimate their native cousins, only the natives don’t usually have entire industries and governments pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into supporting them. Grames compared the situation to birds, another sector in which maladies common in farmed animals, such as bird flu, threaten their wild cousins.

“You wouldn’t be like, ‘Hey, birds are doing great. We’ve got a huge biomass of chickens!’ It’s kind of the same thing with honeybees,” she said. “They’re domesticated. They’re essentially livestock.”

Mace Vaughan leads pollinator and agricultural biodiversity at Xerces, an insect-conservation outfit that has grown from five to nearly 80 employees during his 24 years there. Vaughan says it’s not a zero-sum game: For native pollinators to win, honeybees don’t have to lose. If we focus not on tax breaks, but on limiting the use of insecticide and promoting habitats such as meadows, hedgerows and wetlands, all pollinators can come out ahead.

“We’ve got really well-meaning people who are keeping honeybees because, ‘Oh, I’ve got to save the bees.’ That’s not the way you save the bees!” Vaughan told us. “The way you support both honeybees and beekeepers — and the way you save native pollinators — is to go out there and create beautiful flower-rich habitat on your farm or your garden.”

Howdy! The Department of Data seeks your quantitative queries. What are you curious about: Should we pay blood donors? When does spring really start? What’s the best time to get your flu shot? Just ask!

If your question inspires a column, we’ll send you an official Department of Data button and ID card. This week we owe one to ace news researcher Razzan Nakhlawi, who helped us track down several bee-data experts.

You may like

Personal Finance

Summer Fridays are increasingly rare as hybrid schedules gain steam

Published

22 hours agoon

June 13, 2025

People enjoy an unusually warm day in New York City as temperatures reach the low 80s on June 4, 2025 in New York City.

Spencer Platt | Getty Images

Summer Fridays may be considered the most desirable perk of the season, but fewer employers are on board with the shortened workweek.

Companies have steadily phased out summer Fridays — a policy that allows workers to take Friday afternoon off over the summer months — as work-from-home Fridays became more common, experts say.

“Pre-pandemic, summer Fridays were thing, but hybrid overall has taken over,” said Bill Driscoll, technology workplace trends expert at staffing and consulting firm Robert Half.

As more commuters settle into flexible working arrangements, fewer workers are making Friday trips at all compared to mid-week traffic patterns, according to the 2024 Global Traffic Scorecard released in January by INRIX Inc., a traffic-data analysis firm.

More from Personal Finance:

Job market is ‘trash’ right now, career coach says

Millions would lose health insurance under GOP megabill

Average 401(k) balances drop 3% due to market volatility

Among employees, however, summer Fridays are the most valued summer benefit, followed by summer hours and flextime, according to a new survey by job site Monster, which polled more than 400 U.S. workers in June.

“Summer Fridays are highly valued among workers because, for many, they represent more than just a few extra hours off,” said Scott Blumsack, Monster’s chief strategy and marketing officer. This perk “can go a long way in showing employees they’re valued, which can help prevent burnout, boost morale, and improve retention during a season when disengagement can run high.”

Still, 84% of workers are not offered any summer-specific benefits, even though 55% also said those benefits improve productivity, Monster found.

Instead, hybrid — and to a lesser extent fully remote — job postings have increased in the last year as employers compete for talented job seekers who prioritize flexibility, according to research by Robert Half.

“Hybrid is a highly desirable situation right now and one that all levels of employees are looking for,” said Robert Half’s Driscoll.

More than five years after the pandemic, 72% of organizations also have return-to-office mandates, according to a separate hybrid work study by Cisco.

But, even with the mandates, employees are less likely to work in the office on Fridays, and much more likely to commute Monday to Thursday, Cisco found.

Employees value flexibility

As employee burnout and disengagement grows amid the wave of in-office mandates, work-life balance and flexible hours have become increasingly important, other studies show.

Corporate wellness company Exos, which works with large organizations such as JetBlue and Adobe, says burnout has gone down significantly among employees at firms that have made Fridays more flexible. Exos also tested out “You Do You Fridays” — and found significant benefits.

The more adaptable the schedule, the more positively employees view their company’s policies, the Cisco report also found.

With hybrid arrangements now common, workers put a high value on that flexibility — and 63% of all workers would even accept a pay cut for the option to work remotely more often, according to Cisco’s global survey of more than 21,500 employers and employees working full-time.

Personal Finance

How House Republicans’ ‘big beautiful’ bill may affect children

Published

23 hours agoon

June 13, 2025

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., pictured at a press conference after the House narrowly passed a bill forwarding President Donald Trump’s agenda on May 22 in Washington, DC.

Kevin Dietsch | Getty Images

House reconciliation legislation, also known as the One, Big, Beautiful Bill, includes changes aimed at helping to boost family’s finances.

Those proposals — including $1,000 investment “Trump Accounts” for newborns and an enhanced maximum $2,500 child tax credit — would help support eligible parents.

Proposed tax cuts in the bill may also provide up to $13,300 more in take-home pay for the average family with two children, House Republicans estimate.

“What we’re trying to do is help hardworking Americans who are trying to provide for their families and make ends meet,” House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., said during a June 8 interview with ABC News’ “This Week.”

Yet the proposed changes, which emphasize work requirements, may reduce aid for children in low-income families when it comes to certain tax credits, health coverage and food assistance.

Households in the lowest decile of the income distribution would lose about $1,600 per year, or about 3.9% of their income, from 2026 through 2034, according to a June 12 letter from the Congressional Budget Office. That loss is mainly due to “reductions in in-kind transfers,” it notes — particularly Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, formerly known as food stamps.

20 million children won’t get full $2,500 child tax credit

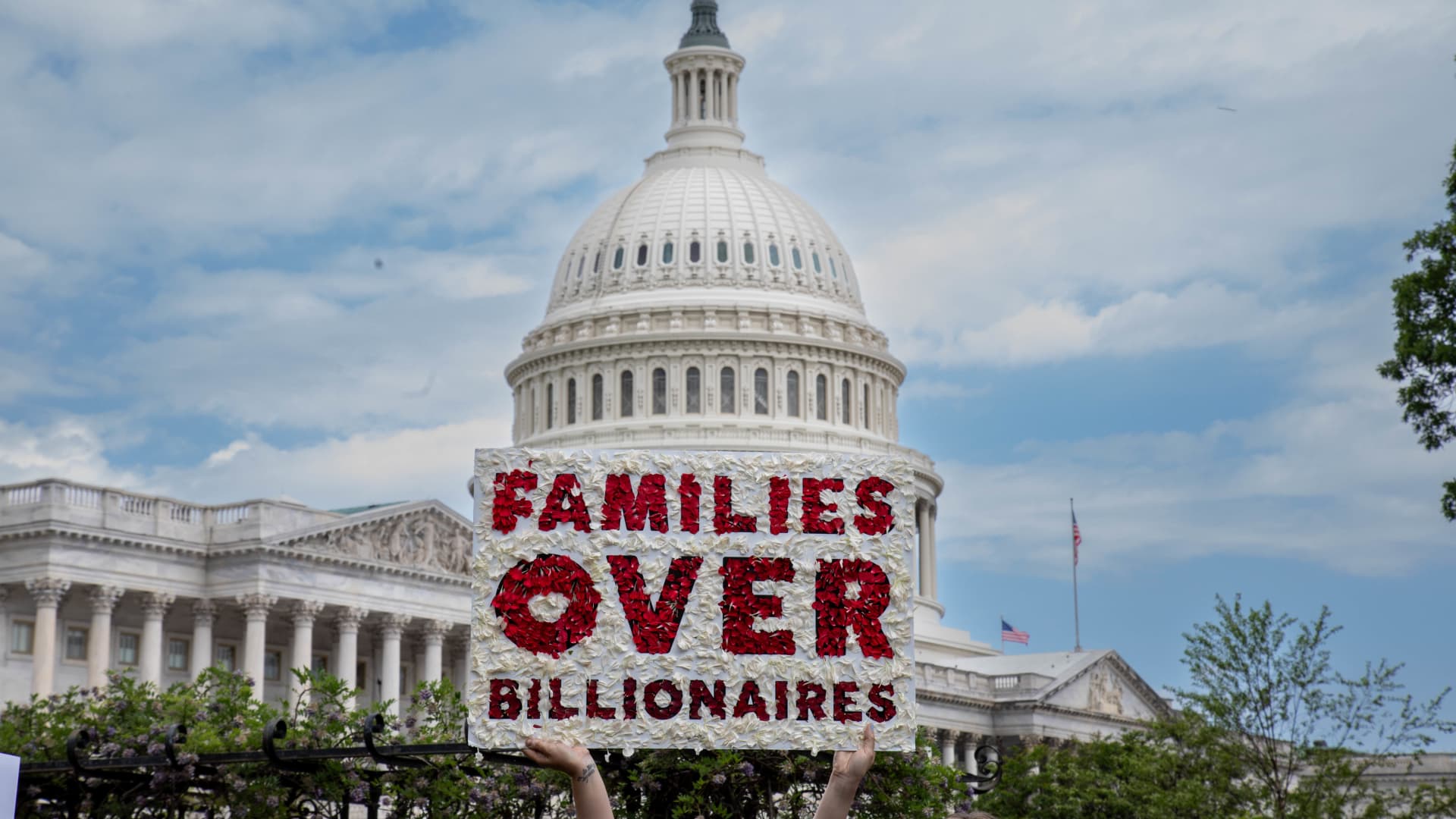

A member of MomsRising holds a sign on Capitol Hill to urge lawmakers to reject tax breaks for billionaires and protest cuts to Medicaid and child care on Capitol Hill on May 8 in Washington, D.C.

Brian Stukes | Getty Images Entertainment | Getty Images

House Republicans have proposed increasing the maximum child tax credit to $2,500 per child, up from $2,000, a change that would go into effect starting with tax year 2025 and expire after 2028.

The change would increase the number of low-income children who are locked out of the child tax credit because their parents’ income is too low, according to Adam Ruben, director of advocacy organization Economic Security Project Action. The tax credit is not refundable, meaning filers can’t claim it if they don’t have a tax obligation.

Today, there are 17 million children who either receive no credit or a partial credit because their family’s income is too low, Ruben said. Under the House Republicans’ plan, that would increase by 3 million children. Consequently, 20 million children would be left out of the full child tax credit because their families earn too little, he said.

“It is raising the credit for wealthier families while excluding those vulnerable families from the credit,” Ruben said. “And that’s not a pro-family policy.”

A single parent with two children would have to earn at least $40,000 per year to access the full child tax credit under the Republicans’ plan, he said. For families earning the minimum wage, it may be difficult to meet that threshold, according to Ruben.

In contrast, an enhanced child tax credit put in place under President Joe Biden made it fully refundable, which means very low-income families were eligible for the maximum benefit, according to Elaine Maag, senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

In 2021, the maximum child tax credit was $3,600 for children under six and $3,000 for children ages 6 to 17. That enhanced credit cut child poverty in half, Maag said. However, immediately following the expiration, child poverty increased, she said.

The current House proposal would also make about 4.5 million children who are citizens ineligible for the child tax credit because they have at least one undocumented parent who files taxes with an individual tax identification number, Ruben said. Those children are currently eligible for the child tax credit based on 2017 tax legislation but would be excluded based on the new proposal, he said.

New red tape for a low-income tax credit

House Republicans also want to change the earned income tax credit, or EITC, which targets low- to middle-income individuals and families, to require precertification to qualify.

When a similar requirement was tried about 20 years ago, it resulted in some eligible families not getting the benefit, Maag said. The new prospective administrative barrier may have the same result, she said.

More than 2 million children’s food assistance at risk

Momo Productions | Digitalvision | Getty Images

House Republican lawmakers’ plan includes almost $300 billion in proposed cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, through 2034.

SNAP currently helps more than 42 million people in low-income families afford groceries, according to Katie Bergh, senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Children represent roughly 40% of SNAP participants, she said.

More than 7 million people may see their food assistance either substantially reduced or ended entirely due to the proposed cuts in the House reconciliation bill, estimates CBPP. Notably, that total includes more than 2 million children.

“We’re talking about the deepest cut to food assistance ever, potentially, if this bill becomes law,” Bergh said.

More from Personal Finance:

Experts weigh pros and cons of $1,000 Trump baby bonus

How Trump spending bill may curb low-income tax credit

Why millions would lose health insurance under House spending bill

Under the House proposal, work requirements would apply to households with children for the first time, Bergh said. Parents with children over the age of 6 would be subject to those rules, which limit people to receiving food assistance for just three months in a three-year period unless they work a minimum 20 hours per week.

Additionally, the House plan calls for states to fund 5% to 25% of SNAP food benefits — a departure from the 100% federal funding for those benefits for the first time in the program’s history, Bergh said.

States, which already pay to help administer SNAP, may face tough choices in the face of those higher costs. That may include cutting food assistance or other state benefits or even doing away with SNAP altogether, Bergh said.

While the bill does not directly propose cuts to school meal programs, it does put children’s eligibility for them at risk, according to Bergh. Children who are eligible for SNAP typically automatically qualify for free or reduced school meals. If a family loses SNAP benefits, their children may also miss out on those benefits, Bergh said.

Health coverage losses would adversely impact families

A protestor holds a sign on May 7, 2025 in Washington, D.C.

Leigh Vogel | Getty Images Entertainment | Getty Images

Families with children may face higher health care costs and reduced access to health care depending on how states react to federal spending cuts proposed by House Republicans, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The House Republican bill seeks to slash approximately $1 trillion in spending from Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program and Affordable Care Act marketplaces.

Medicaid work requirements may make low-income individuals vulnerable to losing health coverage if they are part of the expansion group and are unable to document they meet the requirements or qualify for an exemption, according to CBPP. Parents and pregnant women, who are on the list of exemptions, could be susceptible to losing coverage without proper documentation, according to the non-partisan research and policy institute.

Eligible children may face barriers to access Medicaid and CHIP coverage if the legislation blocks a rule that simplifies enrollment in those programs, according to CBPP.

In addition, an estimated 4.2 million individuals may be uninsured in 2034 if enhanced premium tax credits that help individuals and families afford health insurance are not extended, according to CBO estimates. Meanwhile, those who are covered by marketplace plans would have to pay higher premiums, according to CBPP. Without the premium tax credits, a family of four with $65,000 in income would pay $2,400 more per year for marketplace coverage.

Personal Finance

‘White collar’ jobs are down — but don’t blame AI yet, economists say

Published

24 hours agoon

June 13, 2025

Artificial intelligence makes people more valuable, according to PwC’s 2025 Global AI Jobs Barometer report.

Pixdeluxe | E+ | Getty Images

While there hasn’t been much hiring for so-called “white collar” jobs, the contraction is not because of artificial intelligence, economists say. At least, not yet.

Professional and business services, the industry that represents white-collar roles and middle and upper-class, educated workers, hasn’t experienced much hiring activity over the past two years.

In May, job growth in professional and business services declined to -0.4%, slightly down from -0.2% in April, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In other words, the sector has been losing job opportunities, according to Cory Stahle, an economist at job search site Indeed.

Meanwhile, industries like health care, construction and manufacturing have seen more job creation. In May, nearly half of the job growth came from health care, which added 62,000 jobs, the bureau found.

More from Personal Finance:

Here’s what’s happening with unemployed Americans — in five charts

The pros and cons of a $1,000 baby bonus in ‘Trump Accounts’

Social Security cost-of-living adjustment may be 2.5% in 2026

However, economists have said that the decline in white-collar job openings is more driven by structural issues in the economy rather than artificial intelligence technology taking people’s jobs.

“We know for a fact that it’s not AI,” said Alí Bustamante, an economist and director at the Roosevelt Institute, a liberal think tank.

Indeed’s Stahle agreed: “This is more of an economic story and less of an AI disruption story, at least so far.”

Artificial intelligence is still in early stages

There are a few reasons AI is not behind the declining job creation in white-collar sectors, according to economists.

For one, the decline in job creation has been happening for years, Bustamante said. In that timeframe, AI technology “was pretty awful,” he said.

What’s more, the technology is even now still in early stages, to the point where the software cannot execute key skills without human intervention, said Stahle.

A 2024 report by Indeed researchers found that of the more than 2,800 unique work skills identified, none are “very likely” to be replaced by generative artificial intelligence. GenAI creates content like text or images based on existing data.

Across five scenarios — “very unlikely,” “unlikely,” “possible,” “likely” and “very likely” — about 68.7% of skills were either “very unlikely” or “unlikely” to be replaced by GenAI technology, the site found.

“We might get to a point where they do, but right now, that’s not necessarily looking like it’s a big factor,” Stahle said.

‘Jobs are going to transform’

While AI has yet to replace human workers, there may come a time where the technology does disrupt the labor force.

“Certainly, jobs are going to transform,” Stahle said. “I’m not going to downplay the potential impacts of AI.”

Stahle said that openings for consulting jobs focused on implementing generative AI have been rising. Over the past year, management consulting roles with AI language accounted for 12.4% of GenAI postings, showing signs of growing demand, per a February report by Indeed.

A separate report by the World Economic Forum in January forecasts that by 2030, the new technology will create 170 million new jobs, or 14% of the current total employment.

However, that growth could be offset by the decline in existing roles. The report cites that about 92 million jobs, or 8% of the current total employment, could be displaced by AI technology.

For knowledge-based workers whose skills may overlap with AI, consider investing in developing skills on how to use AI technology to stay ahead, Stahle said.

Amazon is selling an $800 portable power station for $550, and shoppers 'love the mobile design and durability'

Amazon is selling a 'high-quality' $525 Citizen Eco-Drive watch for $260, and buyers love its 'useful functions'

Accounting firms seeing increased profits

New 2023 K-1 instructions stir the CAMT pot for partnerships and corporations

The Essential Practice of Bank and Credit Card Statement Reconciliation

Are American progressives making themselves sad?

Trending

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoJobs report May 2025:

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoDonald Trump has many ways to hurt Elon Musk

-

Economics6 days ago

Economics6 days agoSending the National Guard to LA is not about stopping rioting

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoStocks making the biggest moves midday: WOOF, TSLA, CRCL, LULU

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoDonald Trump has many ways to hurt Elon Musk

-

Blog Post7 days ago

Blog Post7 days agoMastering Bookkeeping Tasks During Peak Business Seasons

-

Personal Finance6 days ago

Personal Finance6 days agoWhat Pell Grant changes in Trump budget, House tax bill mean for students

-

Finance6 days ago

Finance6 days agoChina’s EV race to the bottom leaves a few possible winners