Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., pictured at a press conference after the House narrowly passed a bill forwarding President Donald Trump’s agenda on May 22 in Washington, DC.

Kevin Dietsch | Getty Images

House reconciliation legislation, also known as the One, Big, Beautiful Bill, includes changes aimed at helping to boost family’s finances.

Those proposals — including $1,000 investment “Trump Accounts” for newborns and an enhanced maximum $2,500 child tax credit — would help support eligible parents.

Proposed tax cuts in the bill may also provide up to $13,300 more in take-home pay for the average family with two children, House Republicans estimate.

“What we’re trying to do is help hardworking Americans who are trying to provide for their families and make ends meet,” House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., said during a June 8 interview with ABC News’ “This Week.”

Yet the proposed changes, which emphasize work requirements, may reduce aid for children in low-income families when it comes to certain tax credits, health coverage and food assistance.

Households in the lowest decile of the income distribution would lose about $1,600 per year, or about 3.9% of their income, from 2026 through 2034, according to a June 12 letter from the Congressional Budget Office. That loss is mainly due to “reductions in in-kind transfers,” it notes — particularly Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, formerly known as food stamps.

20 million children won’t get full $2,500 child tax credit

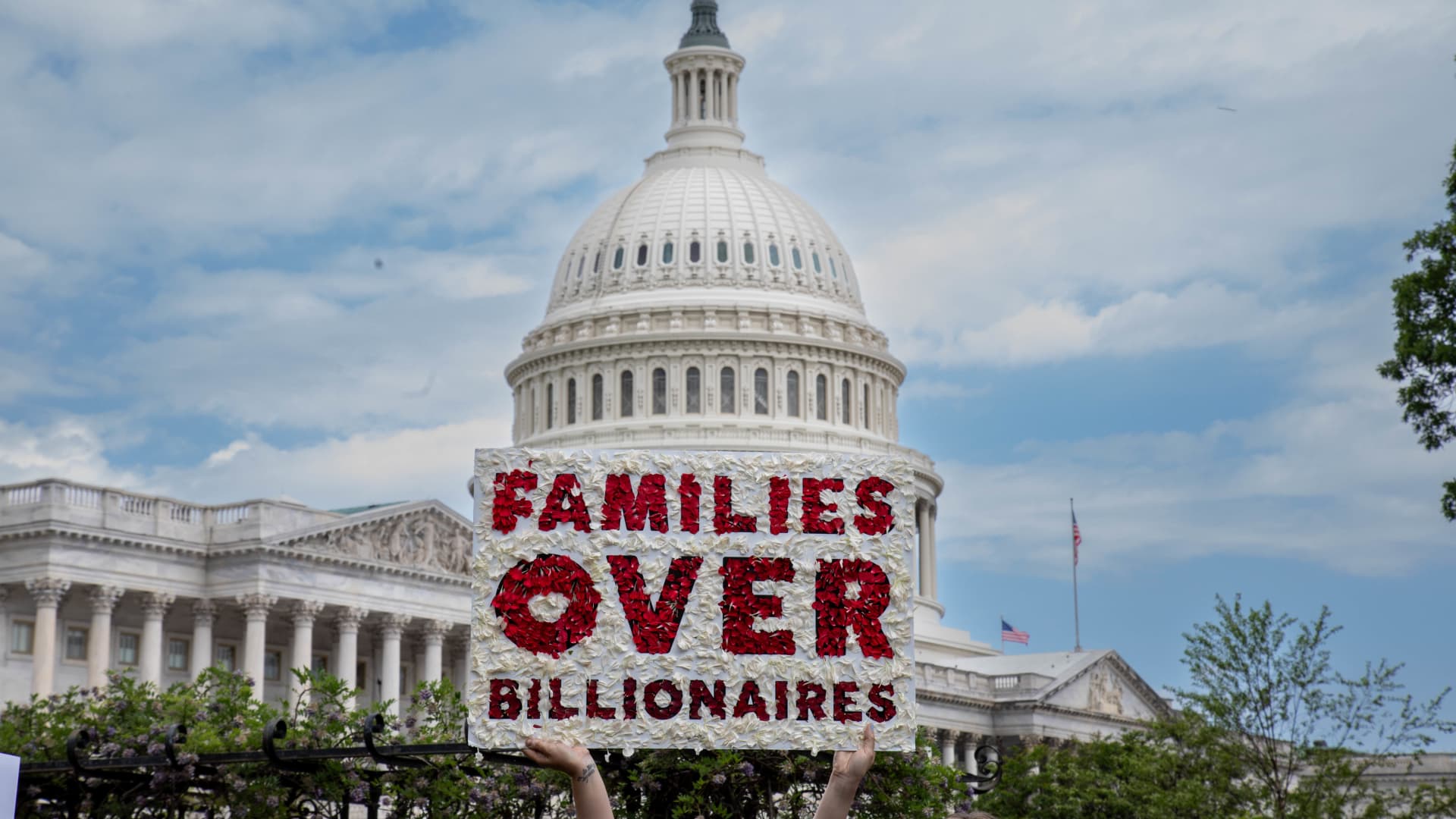

A member of MomsRising holds a sign on Capitol Hill to urge lawmakers to reject tax breaks for billionaires and protest cuts to Medicaid and child care on Capitol Hill on May 8 in Washington, D.C.

Brian Stukes | Getty Images Entertainment | Getty Images

House Republicans have proposed increasing the maximum child tax credit to $2,500 per child, up from $2,000, a change that would go into effect starting with tax year 2025 and expire after 2028.

The change would increase the number of low-income children who are locked out of the child tax credit because their parents’ income is too low, according to Adam Ruben, director of advocacy organization Economic Security Project Action. The tax credit is not refundable, meaning filers can’t claim it if they don’t have a tax obligation.

Today, there are 17 million children who either receive no credit or a partial credit because their family’s income is too low, Ruben said. Under the House Republicans’ plan, that would increase by 3 million children. Consequently, 20 million children would be left out of the full child tax credit because their families earn too little, he said.

“It is raising the credit for wealthier families while excluding those vulnerable families from the credit,” Ruben said. “And that’s not a pro-family policy.”

A single parent with two children would have to earn at least $40,000 per year to access the full child tax credit under the Republicans’ plan, he said. For families earning the minimum wage, it may be difficult to meet that threshold, according to Ruben.

In contrast, an enhanced child tax credit put in place under President Joe Biden made it fully refundable, which means very low-income families were eligible for the maximum benefit, according to Elaine Maag, senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

In 2021, the maximum child tax credit was $3,600 for children under six and $3,000 for children ages 6 to 17. That enhanced credit cut child poverty in half, Maag said. However, immediately following the expiration, child poverty increased, she said.

The current House proposal would also make about 4.5 million children who are citizens ineligible for the child tax credit because they have at least one undocumented parent who files taxes with an individual tax identification number, Ruben said. Those children are currently eligible for the child tax credit based on 2017 tax legislation but would be excluded based on the new proposal, he said.

New red tape for a low-income tax credit

House Republicans also want to change the earned income tax credit, or EITC, which targets low- to middle-income individuals and families, to require precertification to qualify.

When a similar requirement was tried about 20 years ago, it resulted in some eligible families not getting the benefit, Maag said. The new prospective administrative barrier may have the same result, she said.

More than 2 million children’s food assistance at risk

Momo Productions | Digitalvision | Getty Images

House Republican lawmakers’ plan includes almost $300 billion in proposed cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, through 2034.

SNAP currently helps more than 42 million people in low-income families afford groceries, according to Katie Bergh, senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Children represent roughly 40% of SNAP participants, she said.

More than 7 million people may see their food assistance either substantially reduced or ended entirely due to the proposed cuts in the House reconciliation bill, estimates CBPP. Notably, that total includes more than 2 million children.

“We’re talking about the deepest cut to food assistance ever, potentially, if this bill becomes law,” Bergh said.

More from Personal Finance:

Experts weigh pros and cons of $1,000 Trump baby bonus

How Trump spending bill may curb low-income tax credit

Why millions would lose health insurance under House spending bill

Under the House proposal, work requirements would apply to households with children for the first time, Bergh said. Parents with children over the age of 6 would be subject to those rules, which limit people to receiving food assistance for just three months in a three-year period unless they work a minimum 20 hours per week.

Additionally, the House plan calls for states to fund 5% to 25% of SNAP food benefits — a departure from the 100% federal funding for those benefits for the first time in the program’s history, Bergh said.

States, which already pay to help administer SNAP, may face tough choices in the face of those higher costs. That may include cutting food assistance or other state benefits or even doing away with SNAP altogether, Bergh said.

While the bill does not directly propose cuts to school meal programs, it does put children’s eligibility for them at risk, according to Bergh. Children who are eligible for SNAP typically automatically qualify for free or reduced school meals. If a family loses SNAP benefits, their children may also miss out on those benefits, Bergh said.

Health coverage losses would adversely impact families

A protestor holds a sign on May 7, 2025 in Washington, D.C.

Leigh Vogel | Getty Images Entertainment | Getty Images

Families with children may face higher health care costs and reduced access to health care depending on how states react to federal spending cuts proposed by House Republicans, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The House Republican bill seeks to slash approximately $1 trillion in spending from Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program and Affordable Care Act marketplaces.

Medicaid work requirements may make low-income individuals vulnerable to losing health coverage if they are part of the expansion group and are unable to document they meet the requirements or qualify for an exemption, according to CBPP. Parents and pregnant women, who are on the list of exemptions, could be susceptible to losing coverage without proper documentation, according to the non-partisan research and policy institute.

Eligible children may face barriers to access Medicaid and CHIP coverage if the legislation blocks a rule that simplifies enrollment in those programs, according to CBPP.

In addition, an estimated 4.2 million individuals may be uninsured in 2034 if enhanced premium tax credits that help individuals and families afford health insurance are not extended, according to CBO estimates. Meanwhile, those who are covered by marketplace plans would have to pay higher premiums, according to CBPP. Without the premium tax credits, a family of four with $65,000 in income would pay $2,400 more per year for marketplace coverage.

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics6 days ago

Economics6 days ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Blog Post7 days ago

Blog Post7 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Personal Finance6 days ago

Personal Finance6 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago