In recent months, a tug of war over professional sports unleashed untold sturm und/or drang upon our nation’s capital. But the end result of all that sound and fury?

Personal Finance

A sports stadium boom is coming to America. Is that a good thing?

Published

1 year agoon

After all that noise, Washington’s Capitals and Wizards will stay put in Capital One Arena in downtown D.C. Owner Ted Leonsis will not move to a spanking new facility in Northern Virginia.

That got us thinking: Is it just us, or are fewer stadiums and arenas getting built these days?

We ran the numbers. Only six major sports facilities opened in North America from 2020 to 2024 (including the $1.15 billion renovation of Seattle Kraken’s Climate Pledge Arena, the one case of an overhaul so complete we counted it as a new facility). It’s perhaps the steepest stadium slump we’ve seen since the baby boom.

Construction of stadiums and

arenas hit lull after 2005

Sports facilities built in five-year periods

Source: Bradbury, Coates and Humphreys (2022)

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

Stadium and arena construction hit lull after 2005

Sports facilities built in five-year periods

Source: Bradbury, Coates and Humphreys (2022)

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

Construction of stadiums and arenas

hit lull after 2005

Sports facilities built in five-year periods

Source: Bradbury, Coates and Humphreys (2022)

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

What gives? Do sports teams already have all the space they need? Have taxpayers grown reluctant to finance these monuments to the vanity of billionaire owners?

We called economist J.C. Bradbury, who helped build a database of all 220 major sports facilities constructed in North America since 1909, updating the data that Judith Grant Long gathered for her 2014 book. Billionaire owners aren’t always forthcoming, so they often base their work on “ballpark” estimates from press accounts and other public sources.

“It’s purposefully, in my opinion, obfuscated from taxpayers,” especially in more controversial cases, said Long, a professor of sports management and urban planning at the University of Michigan who first assembled the data for her PhD dissertation in the early 2000s.

Bradbury, who updated Long’s data from his perch at Kennesaw State University, outlined two great waves of sports construction. The first hit in the 1960s as television brought sports to the masses, revenue rose and newly expansionist leagues sprawled across the country.

Those first “super stadiums” were cavernous concrete buckets meant be filled with multiple sports and events — think Houston’s Astrodome or RFK Stadium in the District. Many were built with public funds and envisioned as public resources.

The second wave hit in the late 1990s: An incredible 56 facilities rose from 1995 to 2004 as owners realized they could tap into fresh fire hydrants of money by swapping their generic sports buckets — most still perfectly functional — for venues tailored to specific sports and larded with restaurants, clubs and luxury suites.

The cost to build those sports spaces more than doubled during that second surge of construction even after adjusting for inflation, from a median of $190 million in the 1980s to around $480 million in the 2000s.

Sports facility costs grew

faster than public subsidies

Median cost for stadiums opening each

decade, in 2020 dollars

Source: Bradbury, Coates and Humphreys (2022)

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/ THE WASHINGTON POST

Sports facility costs grew faster than public subsidies

Median cost for stadiums opening each decade, in 2020 dollars

Source: Bradbury, Coates and Humphreys (2022)

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/ THE WASHINGTON POST

Sports facility costs grew faster than

public subsidies

Median cost for stadiums opening each decade,

in 2020 dollars

Source: Bradbury, Coates and Humphreys (2022)

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/ THE WASHINGTON POST

Costs have tripled since the 2010s as facilities become more opulent. Much of that increase has fallen on team owners. But the median public subsidy for an arena or stadium has also grown steadily, from $122 million in the 1980s to $500 million since 2020.

What is the public actually paying for? For the answer, we turned to Geoffrey Propheter, a University of Colorado Denver economist who dredged up more than 100 lease agreements for his book, “Major League Sports and the Property Tax.” Propheter said today’s sports team leases are “complex legal artifacts” with hundreds of pages detailing byzantine financial arrangements that somehow always manage to lower owners’ operating costs and/or their tax burdens.

If you were working on one of these deals, your first move might be to take a chunk out of your property tax bill by giving the dirt under the stadium to the local government, making it — voilà! — untaxed public land. In some places, you would still owe property taxes on the building above the land and on the value of your temporary possession of the land over the term of your lease. But maybe not! Lawmakers might exempt you entirely or count your property tax payments as credit toward rent.

You might even give the building to the local government as soon as the lease is up, when its most profitable days are behind it, leaving taxpayers with “a giant paperweight,” Propheter told us. “Now they’ve got to do something with this pile of concrete and steel,” especially if the lease includes a noncompete clause with a new arena or stadium — and that something might be demolition.

Propheter’s data shows sports team leases, like bell-bottom pants and confused cicadas, are on a roughly 30-year cycle with nearly three-quarters lasting between 25 and 40 years. Since the last sports building boom started around 1995, we could be staring down the barrel of another construction wave: The leases of about 44 teams across four different leagues will expire in the next decade.

More than half of NFL leases ending in next 10 years

Sports facility leases for active major league teams in the U.S.

NFL: 60% of leases ending in next 10 years

Lease ends

between

‘25 and ’34

Only includes teams in publicly-owned facilities

or privately-owned facilities on public land

Source: Geoffrey Propheter

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

More than half of NFL leases ending

over next 10 years

Sports facility leases for U.S. major league teams

NFL: 60% of leases ending in next 10 years

Lease ends

between

‘25 and ’34

Only includes teams in publicly-owned facilities or

privately-owned facilities on public land

Source: Geoffrey Propheter

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

More than half of NFL leases ending in next 10 years

Sports facility leases for active U.S. major league teams

NFL: 60% of leases ending in next 10 years

Leases ending

between 2025

and 2034

Only includes teams in publicly-owned facilities or privately-owned facilities on public land

Source: Geoffrey Propheter

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

More than half of NFL leases ending in next 10 years

Sports facility leases for active U.S. major league teams

NFL: 60% of leases ending in next 10 years

Leases ending between

2025 and 2034

Only includes teams in publicly-owned facilities or privately-owned facilities on public land

Source: Geoffrey Propheter

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

If the majority of those team owners get new facilities, it could produce one of the greatest stadium-construction frenzies in modern history, easily surpassing the Y2K era in sheer dollar terms. Even renovations can have a stunning price tag: The overhaul of Capital One Arena — built for $200 million in 1997 (about $385 million in today’s dollars) — is set to receive a $515 million infusion from D.C. on top of the more than $200 million Leonsis has paid to upgrade the arena since 2014.

You might wonder: Do we need new stadiums? Is something wrong with today’s ballparks?

Not really, unless you consider not raking in as much money as humanly possible to be a defect.

A new stadium ignites what economists call the novelty effect, as interest in the new digs enables owners to crank up ticket prices. Revenue soars in the first few years and remains higher than normal for a decade. A new stadium also lets you copy all the profit-making mechanisms your competitors invented in the decades since you last built a facility, such as spendy dining options and luxury suites with wall-consuming televisions.

The latest trend seems to be sprawling mixed-use developments that promise to create urban entertainment hubs, such as the Battery Atlanta around Georgia’s Truist Park. According to Long, owners are using venue construction “as a Trojan horse … to control larger swaths of land.” By unlocking powerful real estate development tools, a new stadium allows a team owner to create a broader development that captures even more revenue — which, in this case, once went to ordinary barkeeps and restaurant owners hoping to serve the game-day crowds.

“This is often pitched as additional economic development impact,” said Nathan Jensen, a University of Texas at Austin subsidy expert and technically an NFL owner: He grew up in Wisconsin and owns a single share of the Green Bay Packers. But as a result, “people going out for a beer before a game are captured by the developer and are subsidized.”

We may be seeing basic economics at work. New stadiums typically enjoy hundreds of millions of dollars in incentives from local governments. And when you subsidize something, you get more of it, whether you want it or not. Propheter has found that subsidized facilities also tend to be more opulent than their private peers.

Are those subsidies a wise economic investment? Reams of research show that new sports venues don’t generally create promised economic booms. A massive analysis of 42 years of professional sports teams and facilities found that the overall sports environment had an impact on wages — but, uh, not always a positive one. Data on employment and sales found similar results. For example, restaurants and bars near Chesapeake Energy Arena in Oklahoma City benefited from their new neighbor, but others — including nearby entertainment businesses — suffered.

The reality is that money spent on sports doesn’t come out of thin air. It is money that fans might have spent elsewhere. Arenas and stadiums can revitalize a neighborhood by pulling spending from other parts of town, but that’s different from creating new economic activity. While every ownership group argues that their new facility will rejuvenate half the city and make a profit for taxpayers, research shows that sports subsidies simply do not generate the kind of economic benefits they promise to the public.

According to Long, predictions about job creation and sales tax revenue tend to come from the same handful of consultants reusing the same methods that have been inaccurate in the past. On top of that, teams often lowball their estimates of construction costs by covering only part of the true public price tag, leaving out unsexy essentials like sanitation services or transportation infrastructure.

Operating expenses add another wrinkle. Consider Barclays Center in Brooklyn, whose financials our new hero Propheter went through with a fine-toothed comb. Its developer, Forest City Ratner, predicted the arena would make a profit of about $35 million annually. In its first three years, revenue actually beat expectations. But Forest City Ratner’s forecasts dramatically underestimated the arena’s operating and debt-servicing costs, which were about twice as high as expected, driving profits down from $35 million to a maximum of $6 million per year.

Expenses exceeded forecasts

at Barclays Center

Expenses include operating expenses and

debt servicing

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

Expenses far exceeded forecasts at Barclays Center

Expenses include operating expenses and debt servicing

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

Expenses exceeded forecasts at Barclays Center

Expenses include operating expenses and debt servicing

DEPARTMENT OF DATA/THE WASHINGTON POST

So why do local officials keep shoveling out money for new stadiums and arenas? It’s partly that sports owners threaten to leave, as Leonsis did late last year, but it’s not just that. Teams have been known to get new facilities without another suitor waiting in the wings.

Data can’t really help here, but according to Bradbury, powerful people may just like sports.

“Politicians love two things: jocks and movie stars,” he told us. And it’s bipartisan: “Democrat and Republican can both agree, ‘We’ve got to have a stadium.’”

Hello there, Data Hive! The Department of Data craves questions. What are you curious about: How have major cities skylines changed over the decades? What are Wall Street’s biggest investors? How did our spending change after the coronavirus pandemic? Just ask!

If your question inspires a column, we’ll send you an official Department of Data button and ID card. This week’s button goes to Nathan Cutler in San Salvador, who asked about the economic impact of stadiums on neighborhoods.

You may like

Personal Finance

‘SALT’ deduction in limbo as Senate Republicans unveil tax plan

Published

7 hours agoon

June 16, 2025

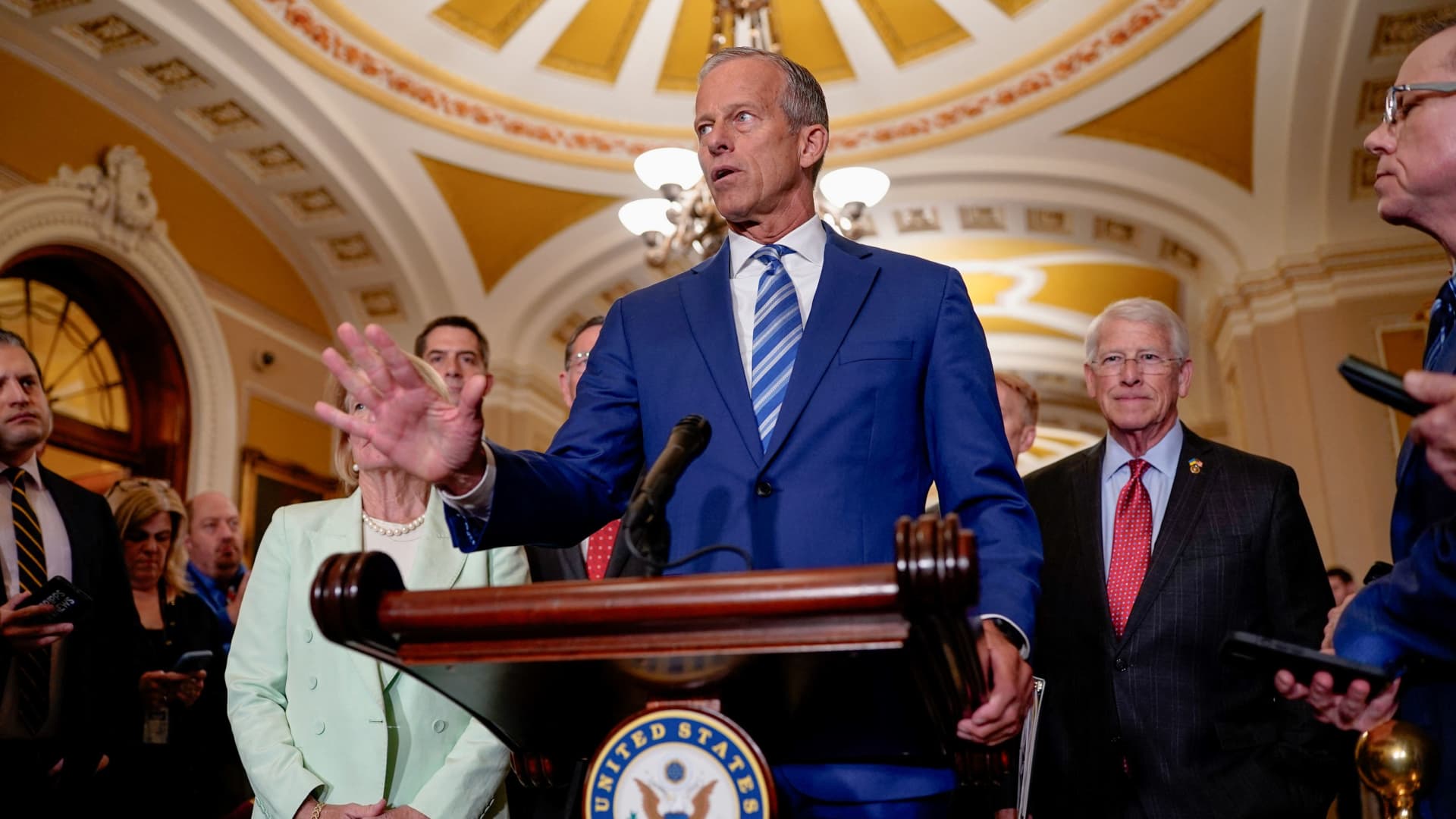

U.S. Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) speaks at a press conference following the U.S. Senate Republicans’ weekly policy luncheon on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., U.S., June 10, 2025.

Kent Nishimura | Reuters

As Senate Republicans release key details of President Donald Trump‘s spending package, some provisions, including the federal deduction for state and local taxes, known as SALT, remain in limbo.

Enacted via the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, or TCJA, of 2017, there’s currently a $10,000 limit on the SALT deduction through 2025. Before 2018, the tax break — including state and local income and property taxes — was unlimited for filers who itemized deductions. But the so-called alternative minimum tax reduced the benefit for some higher earners.

The Senate Finance Committee’s proposed text released on Monday includes a $10,000 SALT deduction cap, which is expected to change during Senate-House negotiations on the spending package. That limit is down from the $40,000 cap approved by House Republicans in May.

More from Personal Finance:

Fed is likely to hold rates steady this week. What it means for you

How to protect assets amid immigration raids, deportation worries

IRS: Make your second-quarter estimated tax payment by June 16

The SALT deduction has been ‘contentious’

“SALT has been contentious for eight years,” said Andrew Lautz, associate director for the Bipartisan Policy Center’s economic policy program.

Since 2017, the SALT deduction cap has been a key issue for certain lawmakers in high-tax states like New York, New Jersey and California. These House members have leverage during negotiations amid a slim House Republican majority.

Under current law, filers who itemize tax breaks can’t claim more than $10,000 for the SALT deduction, including married couples filing jointly, which is considered a “marriage penalty.”

However, raising the SALT deduction cap has been controversial. If enacted, benefits would primarily flow to higher-income households, according to a May analysis from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Currently, the vast majority of filers — roughly 90%, according to the latest IRS data — use the standard deduction and don’t benefit from itemized tax breaks.

Plus, the 2017 SALT cap was enacted to help pay for other TCJA tax breaks, and some lawmakers support the lower limit for funding purposes.

In the Senate, “there isn’t a high level of interest in doing anything on SALT,” Senate Majority Leader John Thune said June 15 on “Fox News Sunday.”

“I think at the end of the day, we’ll find a landing spot, hopefully that will get the votes that we need in the House, a compromise position on the SALT issue,” he said.

But some House Republicans have already pushed back on the proposed $10,000 SALT deduction cap included in the Senate draft.

Rep. Mike Lawler, R-N.Y., on Monday described the Senate proposed $10,000 SALT deduction limit as “DEAD ON ARRIVAL” in an X post.

Meanwhile, Rep. Nicole Malliotakis, R-N.Y., on Monday also posted about the $10,000 cap on X. She said the lower limit was “not only insulting but a slap in the face to the Republican districts that delivered our majority and trifecta.”

Personal Finance

Welcome to the zoo. That’ll be $47 today — ask again tomorrow.

Published

12 hours agoon

June 16, 2025

Giant panda Bao Li chews on bamboo during his public debut at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, U.S., January 24, 2025.

Kevin Lamarque | Reuters

How much will it cost to visit a museum, zoo or aquarium this summer? The answer, increasingly, is: It depends.

John Linehan can rattle off almost two dozen factors that Zoo New England’s dynamic pricing contractor, Digonex, uses to recommend what to charge guests.

“It’s complicated,” said Linehan, president and CEO of the operator of the two zoos in eastern Massachusetts.

Before adopting dynamic pricing, the organization was changing prices seasonally and increasing entry rates little by little. “As we watched that pattern, we were afraid some families were going to get priced out,” he said of the earlier approach. “I’m a father of four and I know what it is like.”

Now, Zoo New England’s system provides cheaper rates for tickets purchased far in advance. That, coupled with the zoo’s participation in the Mass Cultural Council’s discounted admissions program for low-income and working families, “puts some control back in the consumer’s hands,” Linehan said.

We charge what we need to make ends meet while delivering on our mission.

John Linehan

CEO of Zoo New England

The zoo is one of many attractions embracing pricing systems that were earlier pioneered by airlines, ride-hailing apps and theme parks. While these practices allow operators to lower prices when demand is soft, they also enable the reverse, threatening to squeeze consumers who are increasingly trimming their summer travel budgets.

Before the pandemic, less than 1% of attractions surveyed by Arival, a tourism market research and events firm, used variable or dynamic pricing. Today, 17% use variable pricing, in which entry fees are adjusted based on predictable factors such as the day of the week or the season, Arival said. And 6% use dynamic pricing, in which historical and real-time data on weather, staffing, demand patterns and more influence rates.

The changes come as barely half of U.S. museums, zoos, science centers and similar institutions have fully recovered to their pre-Covid attendance levels, according to the American Alliance of Museums. That has led many to pursue novel ways of filling budget gaps and offsetting cost increases.

“There’s a saying: ‘No margin, no mission,'” Linehan said, “and we charge what we need to make ends meet while delivering on our mission.”

Entry costs are climbing even at attractions that aren’t using price-setting technology. The broad “admissions” category in the federal government’s Consumer Price Index, which includes museum fees alongside sports and concert tickets, climbed 3.9% in May from the year before, well above the annual 2.4% inflation rate.

In 2024, the nonprofit Monterey Bay Aquarium raised adult ticket prices from $59.95 to $65 and recently upped its individual membership rate, which includes year-round admission, from $95 to $125. “Gate admission from ticket sales funds the core operation of the aquarium,” a spokesperson said.

While the Denver Art Museum has no plans to test dynamic pricing, it raised admissions fees last fall, three years after a $175 million renovation and a survey of ticket prices elsewhere, a spokesperson said. Entry costs went from $18 to $22 for Colorado residents and from $22 to $27 for out-of-state visitors. Prices rise on weekends and during busy times, to $25 and $30 for in- and out-of-state visitors, respectively. Guests under age 19 always get in free thanks to a sponsored program.

Some attractions are doing a daily analysis of their bookings over the next several days or weeks and making adjustments.

Douglas Quinby

CEO of Arival

Like many attractions, the art museum posts these prices on its website. But many attractions’ publicly listed ticket prices are liable to fluctuate. The Seattle Aquarium — which raised its price ranges last summer by about $10 ahead of the opening of a new ocean pavilion — also uses Digonex’s algorithmic recommendations.

During the week of June 8, for example, the aquarium’s online visit planner, which displays the relative ticket availability for each day, offered out-of-state adult admissions as low as $37.95 for dates later in the month and as much as $46.95 for walk-in tickets that week. In addition to booking in advance, there are more than half a dozen other discounts available to certain guests, including seniors and tribal and military members, a spokesperson noted.

At many attractions, however, admission fees aren’t even provided until a guest enters the specific day and time they want to visit — making it difficult to know that lower prices may be available at another time.

“Some attractions are doing a daily analysis of their bookings over the next several days or weeks and making adjustments” to prices continuously, said Arival CEO Douglas Quinby. Prices might rise quietly on a day when slots are filling up and dip when tickets don’t seem to be moving, he said.

Digonex, which says it provides automated dynamic pricing services to more than 70 attractions worldwide, offers recommendations as frequently as daily. It’s up to clients to decide how and whether to implement them, a spokesperson said. Each algorithm is tailored to organizations’ goals and can account for everything from weather to capacity constraints and even Google Analytics search patterns.

Data-driven pricing can be “a financial win for both the public and the museum,” said Elizabeth Merritt, vice president of strategic foresight at the American Alliance of Museums. It can reduce overcrowding, she said, while steering budget-minded guests toward dates that are both cheaper and less busy.

The stegosaurus fossil nicknamed Apex is unveiled to the media at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, December 5, 2024. Billionaire Kenneth C. Griffin, who bought the stegosaurus fossil for $44.6 million, is loaning it to the museum for four years.

Timothy A. Clary | Afp | Getty Images

But steeper prices during peak periods and for short-notice visits could rankle guests — who may see anything less than a top-notch experience as a rip-off, said Stephen Pratt, a professor at the University of Central Florida’s Rosen College of Hospitality Management who studies tourism.

“Because of the higher prices, you want an experience that’s really great,” he said, transforming a low-key day at the zoo into a big-ticket, high-stakes outing. “You’ve invested this money into family time, into creating memories, and you don’t want any service mishaps.”

That could raise the risk of blowback at many attractions, especially those grappling with Trump administration cuts this summer. Some historic sites and national parks have already warned that their operations are under pressure.

Consumers should expect more price complexity to come. Arival said 16% of attractions ranked implementing dynamic pricing as a top priority for 2025-26. Among large attractions serving at least half a million guests annually, 37% are prioritizing dynamic pricing, up from the 12% that use it currently.

For visitors, that could mean hunting harder for cheaper tickets. While many museums are free year-round, others provide lower rates for off-season visits and those booked in advance. It’s also common to reduce or waive fees on certain days or hours, and many kids and seniors can often get discounted entry.

Here are a few other ways to keep admissions costs low:

Ways to save on museum tickets:

- Ask your local library. Many have museum passes that cardholders can check out.

- Bundling programs such as CityPass, GetOutPass, Go City and others allow visitors to save money on admissions to a range of attractions.

- Bank of America’s Museums on Us program offers cardholders free entry to many institutions during the first full weekend of each month.

- For the past decade, Museums for All has been providing free or reduced entry at more 1,400 U.S. museums and attractions to anyone receiving SNAP food assistance benefits.

- And each summer, the Blue Star Museums program offers museum discounts to actively serving military personnel and their families.

“It may take a bit of research,” said Quinby, “but it’s still possible to find a good deal.”

U.S. President Donald Trump looks on as Fed Chair Jerome Powell speaks at the White House in Washington on Nov. 2, 2017.

Carlos Barria | Reuters

Political pressure is mounting against the Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, and yet the Federal Reserve is expected to hold interest rates steady at the end of its two-day meeting this week.

Despite a wave of recent attacks on Powell from President Donald Trump, futures market pricing is implying virtually no chance of an interest rate cut, according to the CME Group’s FedWatch gauge.

The president has argued that maintaining a fed funds rate that is too high makes it harder for businesses and consumers to borrow, adding more strain to the U.S. economy. The federal funds rate sets what banks charge each other for overnight lending, but also affects many of the borrowing and savings rates most Americans see every day.

More from Personal Finance:

Here’s the inflation breakdown for May 2025

What’s happening with unemployed Americans — in five charts

The economic cost of Trump, Harvard battle over student visas

With a rate cut likely postponed until at least September, consumers struggling under the weight of high prices and high borrowing costs aren’t getting much relief, experts say.

“The combination of high interest rates, stubborn inflation and economic uncertainty is a pretty challenging one,” said Matt Schulz, chief credit analyst at LendingTree. “Most Americans don’t have a ton of wiggle room and today they have even less.”

From credit cards and mortgage rates to auto loans and savings accounts, here’s a look at how the Fed plays a role in your finances.

Credit cards

Credit card debt continues to be a pain point for consumers struggling to keep up with high prices. Since most credit cards have a variable rate, there’s a direct connection to the Fed’s benchmark.

But even with the Fed on the sidelines, credit card rates have edged higher. The average annual percentage rate is currently just over 20%, according to Bankrate, not far from last year’s all-time high.

“This is a sign of banks trying to protect themselves from the risk that is out there in these uncertain times,” Schulz said. However, in this case, there is something consumers can do about higher APRs.

“The truth is that people have way more power over the rates they pay than they think they do, especially if they have good credit,” Schulz said.

Rather than wait for a rate cut that may be months away, borrowers could switch now to a zero-interest balance transfer credit card or consolidate and pay off high-interest credit cards with a lower-rate personal loan, he said.

Mortgages

Since 15- and 30-year mortgages are largely tied to Treasury yields and the economy, those rates haven’t moved much — and that hasn’t helped would-be buyers.

The average rate for a 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage has stayed within the same narrow range for months and is currently near 6.9%, according to Bankrate. Tack on the nationwide problem of limited inventory and housing affordability remains a key issue, regardless of the Fed’s next move.

“I don’t see any major changes coming in the immediate future, meaning that those shopping for a home this summer should expect rates to remain relatively high,” Schulz said.

Auto loans

Auto loan rates are fixed, and not directly tied to the Fed. But payments are getting bigger because car prices are rising, in part due to impacts from Trump’s trade policy.

Currently, the average rate on a five-year new car loan is 7.24%, according to Bankrate.

The growth in median car payments is outpacing both new and used car prices, according to separate data from Bank of America. Now, of those households with a monthly car payment, 20% pay more than $1,000 a month.

“Combine that with the potential for tariffs to drive auto prices even higher, and it adds up to a really challenging time to buy a car,” Schulz said. “However, shopping for the best rate and getting approved for financing before you ever set foot in the dealership can bring significant savings,” he added.

Student loans

Federal student loan rates are set once a year, based in part on the last 10-year Treasury note auction in May and fixed for the life of the loan, so most borrowers are somewhat shielded from Fed moves and recent economic turmoil.

Current interest rates on undergraduate federal student loans made through June 30 are at 6.53%. Starting July 1, the interest rates will be 6.39%.

Although borrowers with existing federal student debt balances won’t see their rates change, many are now facing other headwinds and fewer federal loan forgiveness options.

Savings

On the upside, top-yielding online savings accounts still offer above-average returns and currently pay more than 4%, according to Bankrate.

While the central bank has no direct influence on deposit rates, the yields tend to be correlated to changes in the target federal funds rate — so holding that rate unchanged has kept savings rates elevated, for now.

“The thing that is lost in this, is that savers, including millions of retirees, are actually earning good income on their savings, provided they have their money parked in a competitive place,” said Greg McBride, Bankrate’s chief financial analyst.

Senate Republicans release revised tax cuts and debt limit bill

Tax savings for business owners hiring kids

‘SALT’ deduction in limbo as Senate Republicans unveil tax plan

New 2023 K-1 instructions stir the CAMT pot for partnerships and corporations

The Essential Practice of Bank and Credit Card Statement Reconciliation

Are American progressives making themselves sad?

Trending

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoSending the National Guard to LA is not about stopping rioting

-

Blog Post1 week ago

Blog Post1 week agoMastering Bookkeeping Tasks During Peak Business Seasons

-

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week agoInstead adds AI-driven tax reports

-

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week agoWhat Pell Grant changes in Trump budget, House tax bill mean for students

-

Personal Finance6 days ago

Personal Finance6 days agoHow markets performed for investors so far

-

Economics6 days ago

Economics6 days agoIs there a “woke right” in America?

-

Personal Finance7 days ago

Personal Finance7 days agoTrump’s ‘big beautiful’ bill may curb access to low-income tax credit

-

Finance6 days ago

Finance6 days agoGundlach says to buy international stocks on dollar’s ‘secular decline’