Two decades ago, a group of senior-housing executives came up with a way to raise revenue and reduce costs at assisted-living homes. Using stopwatches, they timed caregivers performing various tasks, from making beds to changing soiled briefs, and fed the information into a program they began using to determine staffing.

Personal Finance

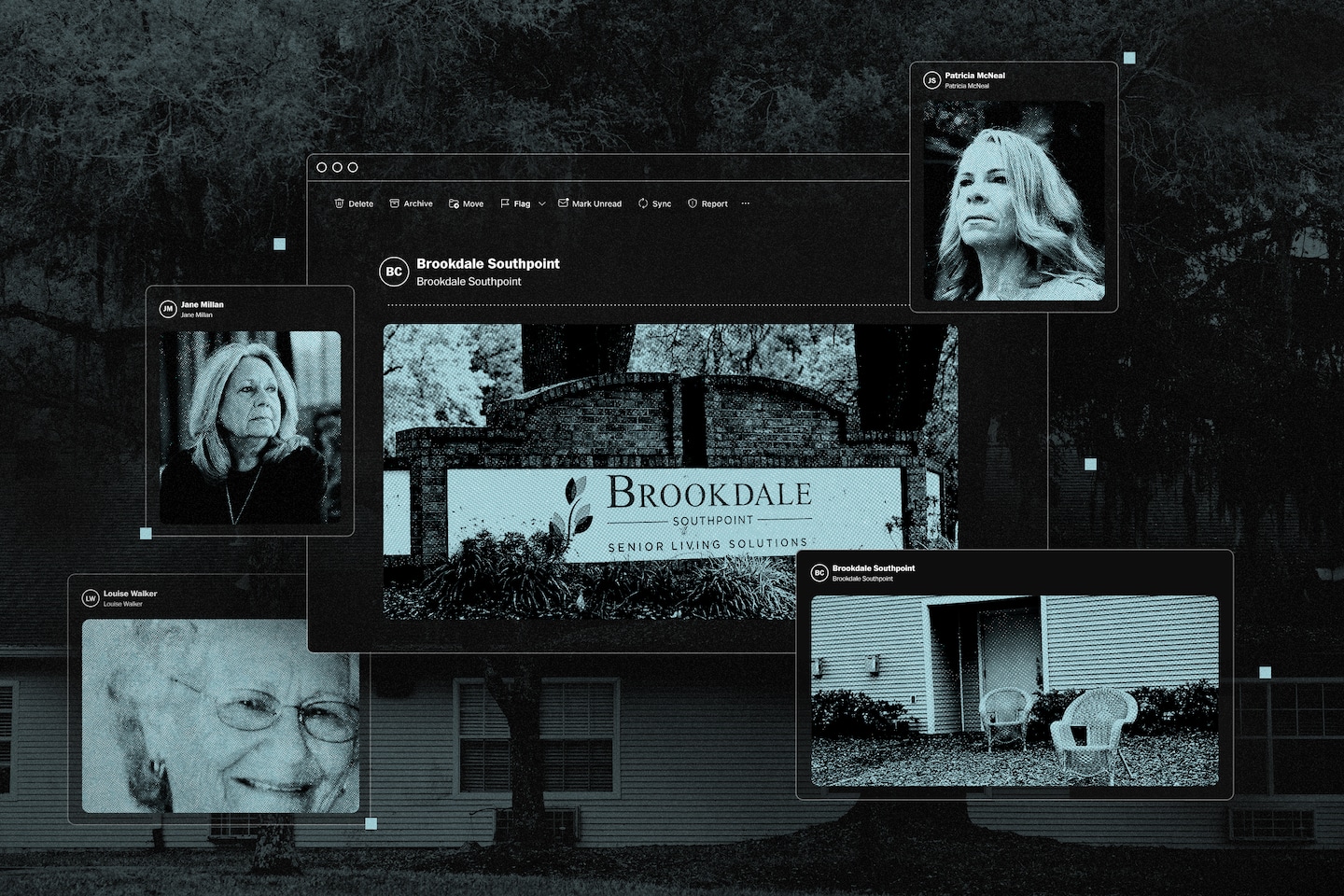

Algorithms guide senior home staffing. Managers say care suffers.

Published

1 year agoon

At a Brookdale facility in Chicago, tiny elevators prevented residents from being herded en masse to dinner, necessitating more trips and more time than Service Alignment allotted. At a facility in New Port Richey, Fla., the algorithm recommended fewer caregivers than buildings, making it impossible to monitor all residents at all times. And at a facility near Fort Worth, residents often could not undress, shower and get dressed again within the allotted 20 minutes — constantly putting caregivers behind in their tasks.

In emails and phone calls to Brookdale executives, building managers repeatedly complained that the company’s algorithm underestimated the amount of labor they needed to meet resident needs, according to court records, internal company documents reviewed by The Washington Post, and interviews with more than 35 current and former Brookdale employees. Several managers said they quit or were fired after objecting to the system, including Patricia McNeal, 53, who spent six years overseeing Brookdale facilities in Ohio and Florida.

“Brookdale is handing you this thing that says, ‘This is what it says you need, hire for that,’” McNeal said. “My eyes told me that we weren’t getting enough” staff to care for residents.

While assisted-living chains promote their properties like all-inclusive resorts with round-the-clock care, many operate more like assembly lines, where low-wage workers perform a series of discrete, predictable tasks, documents and interviews with industry veterans show. Brookdale, based in Brentwood, Tenn., pioneered staffing systems based on algorithmic formulas, an approach experts say is ill-suited to caring for the elderly, who are growing more frail and are more likely to suffer from chronic conditions than previous generations.

In two civil lawsuits against Brookdale — one in Tennessee, one in California — a dozen residents or relatives of residents claim they suffered due to short-staffing caused by an overreliance on algorithms. Sunrise Senior Living, a rival which in 2016 directed all of its facilities to follow its own staffing formula, is also defending a lawsuit by a group of customers who allege similar concerns. A spokeswoman for Sunrise declined to comment, citing pending litigation.

In a statement to The Post, Brookdale spokeswoman Jackie Dickson disputed the allegations in the lawsuits and said that Brookdale empowers local facility managers to set staffing levels as they see fit. Last year, a federal judge denied class-action certification for some of the claims in the California lawsuit, in part because plaintiffs failed to show that facilities are “similarly staffed.”

“Service Alignment is a resource offered to community leaders to assist them with appropriately staffing communities,” Dickson said. “This tool accounts for community-specific layouts and features, the ever-changing needs of residents, as well as applicable regulatory requirements, and is customized based on feedback from local community leaders.”

However, when the company began rolling the algorithm out to all its facilities, in 2013, then-CEO Andrew Smith told financial analysts one of the main goals was “to make sure that we don’t over-staff.”

In the fall of 2020, McNeal said she begged her superiors to send help as she scrambled to care for the rapidly declining health of residents in a Jacksonville facility she managed during the covid pandemic. When help didn’t arrive, McNeal scheduled additional workers as “training” staff without company approval — an action for which Brookdale fired her, documents show, saying she didn’t “demonstrate good stewardship to the company’s resources.”

A few weeks after her termination, Louise Walker, 89, died after falling in her room at the Jacksonville facility. State investigators cited Brookdale for medical neglect, saying workers failed to adequately supervise Walker, a high fall risk who was diagnosed with dementia. At the time, two employees were tending to more than a dozen residents in the dementia care unit, and neither had training on traumatic brain injuries, court records show.

“I don’t blame a lot of the people who work there,” said Jane Millan, 72, Walker’s daughter, whose wrongful-death lawsuit against Brookdale is set for trial in May. “They don’t have enough staff to do the duties they have to do, so something has got to slide.”

Dickson, the Brookdale spokesperson, said McNeal’s account is “inaccurate” but declined to comment on confidential employment matters. She said the company denies any wrongdoing in Walker’s death and declined further comment, citing the litigation.

There are no federal laws regulating assisted-living facilities, and only 13 states require staffing minimums. Brookdale says its algorithm sets staffing levels above statutory minimums in states that require them — a claim disputed by plaintiffs in the Tennessee lawsuit, which has requested class-action certification.

Using time sheet data provided by Brookdale covering seven facilities in North Carolina, an expert for the plaintiffs found that all failed to meet the state’s clinical care staffing minimums during at least 10 percent of shifts from 2016 to 2022. Four facilities fell short of state minimums during at least one out of every three shifts.

An expert hired by Brookdale said in a court filing that the North Carolina analysis failed to account for employees who clock in under one department, such as a cook, but then contributed to caregiving tasks when they had extra time.

In the California lawsuit, relatives of Brookdale residents claimed understaffing contributed to their loved ones being found covered in feces, breaking bones or wandering away unattended. One woman was hospitalized for extreme dehydration because staff had left food and water outside her door for three days straight without checking to see if she consumed any of it, according to her son, who provided a sworn statement in the lawsuit.

The case is scheduled for trial in October.

On Christmas Day 2020, a man was found lying facedown in the courtyard of a Brookdale facility in Destin, Fla. — frozen to death after being left unattended for more than 12 hours, a police investigation found. A caregiver working there that day told police the facility was unsafe because “the staff to resident ratio is horrible” and “they need to have more people working in the facility to keep up” with residents. She said she raised her concerns with Brookdale executives and “nothing was done,” according to the police report. It’s unclear whether this incident led to a lawsuit or whether the company’s algorithm played any role.

Dickson declined to comment on individual residents or facilities but said Brookdale is regularly cited by industry surveys as having high customer satisfaction.

“Brookdale needs to get

rid of Service Alignment

and get more staff in here

on each shift… It’s not

safe and it’s not right.

Something bad is going

to happen and I just

don’twant to be here

when that happens.”

June 2021 email from Virginia Steinman,

former health andwellness director at

Brookdale Morehead City, North Carolina

“Brookdale needs to get rid of Service

Alignment and get more staff in here on

each shift… It’s not safe and it’s not right.

Something bad is going to happen and I just don’t want to be here when that happens.”

June 2021 email from Virginia Steinman, former health and

wellness director at Brookdale Morehead City, North Carolina

The problems of understaffing and questionable levels of care pervade the assisted-living industry. Since 2018, more than 100 residents died after wandering away from such facilities or being left unattended outside, a Post investigation found.

Brookdale, Sunrise and Atria Senior Living, another top chain, were questioned as part of a congressional committee inquiry into concerns about the costs and quality of care at senior living facilities raised by The Post’s reporting. A spokesman for Sen. Bob Casey (D-Pa.), chairman of the Senate’s Special Committee on Aging, said the companies provided some responses to the lawmakers’ questions but the committee has declined to make them public. A spokesperson for Atria said the company prioritizes the safety and well-being of residents.

Brookdale became the industry giant through a wave of mergers between 2005 and 2014. Among them was Alterra Healthcare, which had invented the system for determining staff levels based on stopwatch studies. Brookdale believed the program could help it rein in ballooning expenses and manage its growing empire from afar, according to interviews with former executives and transcripts of the company’s quarterly earnings calls with analysts.

It began rolling out Service Alignment to all its properties between 2013 and 2016 — during which its portfolio ballooned to nearly 1,200 senior homes — executives said on earnings calls. Under the new system, Brookdale would assess the health of every resident and determine exactly which tasks were needed to meet their needs. Using these assessments and the stopwatch time studies, the algorithm promised to tell building managers exactly how many minutes were needed to care for all residents each shift — and, therefore, the number of employees they were permitted to schedule.

Businesses have been timing tasks to improve worker efficiency for over a century. Frederick Taylor, one of the fathers of management consulting, devised the first time study in the late 1800s, when he noticed workers at a steel mill were intentionally doing as little work as they could, said Naren Agrawal, a professor of supply chain management and analytics at Santa Clara University. By understanding the times it took to perform individual tasks, businesses could catch workers who were slacking off and get a clearer picture of the total labor needed to build a product or perform a service, Agrawal said.

Such rigid systems can fail for tasks with wide variability, said Carri Chan, a Columbia Business School professor who researches health-care management and operations. “When you are taking care of patients, all of whom have unique needs, there is going to be a lot of variation,” she said.

In interviews, McNeal and nine other former executive directors of Brookdale facilities said Service Alignment failed to capture the complexities of working with seniors with cognitive decline. For instance, helping dementia patients take showers may take two or three times as long as other residents, because they often refuse to get undressed in front of caregivers they may not remember and need to be patiently guided through the process.

Each time a caregiver runs over time in one task, it takes away from the total caregiving hours for the entire building. As a result, some residents go without showers, rooms are left uncleaned and people needing close supervision are ignored, some of the former managers said.

When Service Alignment was rolled out, the algorithm forced many Brookdale facilities to reduce their staff, documents and interviews show. At other facilities, where the algorithm suggested more staff was needed, Brookdale intervened.

“We are talking about

missing showers and

time gaps on putting

residents in their beds

… I am wide awake at

night thinking about

anything else that may

get overlooked…

I cannot stress to

you how bad it is…

I am asking for help?

August 2021 email from Brenda Jarmer,

district director of operations in Florida.

In a message to The Post, Jarmer said

she wrote that email amid staffing

challenges brought on by the COVID

pandemic and that she believes Brookdale,

where she still works, is a “great company.”

“We are talking about missing showers

and time gaps on putting residents in

their beds… I am wide awake at night

thinking about anything else that may

get overlooked… I cannot stress to you

how bad it is… I am asking for help.”

August 2021 email from Brenda Jarmer, district director of operations in Florida.

In a message to The Post, Jarmer said she wrote that email amid staffing challenges

brought on by the COVID pandemic and that she believes Brookdale,

where she still works, is a “great company.”

Kelly Rubin, a senior director overseeing the staffing system, sent an email to regional managers warning of the likelihood the algorithm would show “favorable variances” in needed labor for some facilities — meaning, they needed more staff. Rubin said no facility would be granted more than two additional full-time employees, regardless of what the algorithm said.

“Just by virtue of flipping a switch from one platform to another does not justify additional labor because the platforms calculate differently,” Rubin wrote in the email, which, like other internal communications quoted in this story, was made public as part of a court record.

Rubin, who still works at Brookdale, said in a message to The Post that Brookdale tended to staff facilities at a “higher level” than the roughly 500 newly acquired properties that it was moving onto Service Alignment so she expected staff increases. Her message was intended to help local managers “evaluate the new platform’s guidance and make any adjustments they felt appropriate based on actual resident needs.”

Staff complaints started pouring in.

In 2016, Sarah Jenkins, a night-shift medication technician at a Brookdale in Jensen Beach, Fla., complained to the company’s internal tip line that short staffing was causing caregivers to cut corners, according to notes from the call included in a court record. Jenkins said her co-workers were applying wet-wipes to residents in lieu of giving them showers and set the thermostat to 64 degrees “because it keeps the residents in bed.” Jenkins, who no longer works for Brookdale, did not respond to a request for comment.

The following year, Jackie Smedley, a divisional director of sales and marketing, emailed a regional manager that “extreme action” was needed to improve resident safety at a facility in Clearwater, Fla., that was “very short on care staff” and had “no clinical oversight.” A resident had arrived at an emergency room with impacted fecal matter stuck to his skin. “The ER reported to Brookdale that this was the worst case of resident abuse they ever witnessed,” she wrote in an email that was included in court papers. Smedley, who no longer works for Brookdale, declined to comment.

Brookdale managers who scheduled more employees than the algorithm advised were required to propose a plan of correction, former employees said. Repeat offenders risked losing portions of their annual bonus. Brookdale’s Dickson called the employees’ description of these practices “inaccurate” but declined to elaborate.

Some managers told their bosses that Service Alignment assumptions must be wrong and asked for exceptions — which they sometimes got.

One example was the facility in Chicago with the small elevators. After sending someone to the building to study transport times, Brookdale agreed to reinstate the staffing level before Service Alignment, according to one of the building’s former managers, who declined to be named because they still work in the industry.

“I am concerned about

the safety and welfare

of our current residents.

If we can’t meet the needs

of current residents,

how can we meet the

needs of new residents?”

July 2017 email from Jackie Smedley,

formersoutheast divisional director

of sales and marketing

“I am concerned about the safety and

welfare of our current residents. If we can’t

meet the needs of current residents, how can

we meet the needs of new residents?”

July 2017 email from Jackie Smedley, former

southeast divisional director of sales and marketing

Other managers said their warnings were not heeded. Greg Brown quit three months after taking a job heading a Brookdale facility in Denver in 2019 because, he said, the algorithm didn’t recognize there were four different buildings and that leaving some of the buildings unattended would be dangerous.

“I quickly realized and explained in my resignation that I didn’t feel they were staffing the community in a correct and safe manner and that I wouldn’t be able to continue,” Brown, who has worked at various senior living homes for over 15 years, said in a direct message on LinkedIn. Brookdale no longer owns the property.

Brookdale’s solution to the wide variation in resident conditions was to charge more when they needed more time for any task than Service Alignment allotted. For example, if a resident routinely took long showers, caregivers were supposed to report that to their managers, who would reassess the resident’s needs, potentially increasing fees.

However, many employees found it difficult to constantly raise prices on the residents with whom they worked every day and who already were paying steep fees, said Saralyn Kerrigan, who ran a Brookdale building in Connecticut from 2011 to 2014.

“Rather than it being like advocating for seniors, making sure they had what they need, it became, what more could we get out of them?” Kerrigan said. “We were really encouraged to be upselling.”

Brookdale charged an extra $156 a month for residents who needed help laying out their clothes and toiletries in the morning, and an extra $703 a month if a resident routinely wandered the hallways and required periodic redirection, according to a pricing sheet for one Texas facility the company provided in a court filing this year.

At one facility earlier this year, Brookdale charged each customer with special cognitive or psychological needs an extra $468 to $703 a month for what averaged to about 14 minutes of additional care per day, according to a daily Service Alignment plan reviewed by The Post. The Post analysis was based on the total number of minutes Brookdale’s algorithm allocated for dementia-related assistance, divided by the number of people in the facility billed for those services.

As managers struggled under the new staffing system, the company’s finances got worse. More than three-quarters of Americans 50 and older want to remain in their homes for the long term, according to a 2021 survey by AARP — a number that has remained constant for more than a decade despite the industry’s marketing efforts and the aging of the nation’s demographics. Until recently, that trend left Brookdale and other industry leaders with too many buildings and not enough residents.

Brookdale lost money in each of the past 19 years except 2020, and its stock price, which peaked at $53 a share in 2006, has petered to just $7.

When McNeal started at Brookdale Southpoint in January 2020, the Jacksonville facility already had difficulty caring for its residents.

The one-story building, sandwiched between a busy intersection and a small pond in a commercial neighborhood south of the city, had been cited by regulators in 2018 for failing to properly supervise a misbehaving male resident who forced his way into the beds of female residents, state documents show. An employee interviewed by state inspectors at the time said “she felt there is nothing they can do to stop him because he is ‘out of his mind’ and he does not understand,” the inspector wrote in the report.

Adding to McNeal’s challenges, covid lockdowns forced residents to spend most of their days alone in their rooms, causing some to rapidly decline. One man became so disoriented he was peeling linoleum off the floor of his room and eating it, McNeal said.

Brookdale Southpoint typically had two to three caregivers assisting more than a dozen residents of the locked memory care unit and another one to two serving more than a dozen additional assisted-living residents, according to former employees and facility records. Because the building had very few dedicated housekeepers and dining staff, caregivers also had to do laundry, clean rooms and help serve meals in between making their rounds delivering medicine and assisting residents with grooming, bathing and going to the bathroom.

Brookdale has defended its practice of “universal caregivers” combining these roles as innovative and efficient. “You’re trying to find useful things that the associates can do overnight, in addition to ensuring that the residents are safe and cared for,” Smith, the former Brookdale CEO, said on a call with financial analysts in 2013. But as residents and their families have discovered, the wide-ranging responsibilities of these workers can take away from their ability to complete their caregiving duties.

A few months after starting at Brookdale Southpoint, McNeal said she discovered that a memory care resident wandered outside at about 11:30 p.m. while her caregiver was doing laundry. The resident remained alone in a wooded area until she was found at close to 7 a.m. the next day.

McNeal said she repeatedly pushed for additional help in conversations with her managers. Several times, Brookdale sent people to help McNeal conduct new health assessments of her residents, but each time, she said, it did not result in her facility getting more hours for additional employees.

Walker, the resident who died at Brookdale Southpoint, moved into the facility in June 2020 and paid $4,650 per month. In April 2021, Walker’s great-granddaughter, Brandi Faison, came by to give her Nannie a pedicure and was startled by the sight of her feet — hardened, yellow and cracking, with thick, curling toenails three to four times their normal length. She was so horrified that she took a photo and shared it with her family, and later shared it with The Post.

Walker, embarrassed by her appearance, told her great-granddaughter that “nobody ever came” to do her nails, Faison recalled.

Shortly after McNeal was fired, a Brookdale caregiver discovered Walker bleeding on the floor of her room. A police investigation found she had been left alone for two hours and 40 minutes, despite a facility policy of checking residents at least every two hours. Walker required extra attention due to “difficulty standing, ambulating, and safely functioning” on her own, according to a nurse practitioner’s note.

Though the hospital was a two-minute drive across the street, Walker was not received by the emergency room until nearly two hours after she was discovered, documents show. She died of a brain hemorrhage four days later. In their report, state investigators cited Brookdale’s failure to properly supervise Walker and the facility’s slow response time as evidence of neglect.

The night of Walker’s fall, the medication technician on duty had been allowed to go home early, leaving Marie Berleus — a Haitian immigrant who spoke limited English working her fourth 12-hour graveyard shift of the week — to puzzle through the medical crisis. Berleus exchanged text messages with her boss and searched for paperwork before finally calling a non-emergency ambulance service, rather than 911, 40 minutes after finding Walker, according to court records from a lawsuit Walker’s family filed against Brookdale. Berleus did not respond to a request for comment.

In court records, Brookdale’s lawyers denied that any of the facility’s actions caused Walker’s death, pointing out that a medical expert hired by the family could not say that a quicker response would have necessarily saved her life.

“I’m so tired,” Berleus wrote in one of her text messages to her boss that night.

The Washington Post is continuing to report on the assisted-living industry, and we want to know your experiences with elder care, assisted living and dementia care. Tell us about your experience here.

You may like

U.S. President Donald Trump announces the NFL draft will be held in Washington, at the White House in Washington, D.C., U.S., May 5, 2025.

Leah Millis | Reuters

As negotiations ramp up for President Donald Trump‘s tax agenda, there are key issues to watch, according to policy experts.

The House Ways and Means Committee, which oversees taxes, released a preliminary partial text of its portion of the bill on Friday evening. However, the bill could change significantly before the final vote. The full committee will debate and advance this legislation on Tuesday.

With control of the White House and both chambers of Congress, Republican lawmakers can pass Trump’s package without Democratic support via a process known as “reconciliation,” which bypasses the Senate filibuster with a simple majority vote.

But reconciliation involves multiple steps, and the proposals must fit within a limited budget framework. That could be tricky given competing priorities, experts say.

More from Personal Finance:

The Fed holds interest rates steady. Here’s what that means for your wallet

IRS loses nearly 1 in 3 tax auditors in DOGE cuts, watchdog finds

What new Social Security head Bisignano may mean for benefits

“The narrow [Republican] majority in the House is going to make that process very difficult” because a handful of votes can block the bill, said Alex Muresianu, senior policy analyst at the Tax Foundation.

Plus, some lawmakers want a “more fiscally responsible package,” which could impact individual provisions, according to Shai Akabas, vice president of economic policy for the Bipartisan Policy Center.

As negotiations continue, here are some key tax proposals that could impact millions of Americans.

Extend Trump’s 2017 tax cuts

The preliminary House Ways and Means text includes some temporary and permanent enhancements beyond the TCJA. These include boosts to the standard deduction, child tax credit, tax bracket inflation adjustments, the estate tax exemption and pass-through business deduction, among others.

Child tax credit expansion

Some lawmakers are also pushing for bigger tax breaks than what’s currently offered via the TCJA provisions.

“The child tax credit is one that we’re watching very closely,” Akabas said. “There’s a lot of bipartisan agreement on preserving and hopefully expanding that.”

TCJA temporarily increased the maximum child tax credit to $2,000 from $1,000 per child under age 17, and boosted eligibility. These changes are scheduled to sunset after 2025.

The House in February 2024 passed a bipartisan bill to expand the child tax credit, which would have boosted access and refundability. The bill didn’t clear the Senate, but Republicans expressed interest in revisiting the issue.

The early House Ways and Means text proposes expanding the maximum child tax credit to $2,500 per child for four years starting in 2025.

‘SALT’ deduction relief

Another TCJA provision — the $10,000 limit on the deduction for state and local taxes, known as “SALT” — was added to the 2017 legislation to help fund other tax breaks. That provision will also expire after 2025.

Before the change, filers who itemized tax breaks could claim an unlimited deduction for SALT. But the so-called alternative minimum tax reduced the benefit for some higher earners.

Repealing the SALT cap has been a priority for certain lawmakers from high-tax states like California, New Jersey and New York. In a policy reversal, Trump has also voiced support for a more generous SALT deduction.

“If you raise the cap, the people who benefit the most are going to be upper-middle-income,” since lower earners typically don’t itemize tax deductions, Howard Gleckman, senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, previously told CNBC.

The SALT deduction was absent from the preliminary House Ways and Means text. But Congressional negotiations are ongoing.

Trump’s campaign ideas

On top of TCJA extensions, Trump has also recently renewed calls for additional tax breaks he pitched on the campaign trail, including no tax on tips, tax-free overtime pay and tax-exempt Social Security benefits. These ideas were not yet included in the early House Ways and Means text.

However, there are lingering questions about the specifics of these provisions, including possible guardrails to prevent abuse, experts say.

For example, you could see a questionable “reclassification of income” to qualify for no tax on tips or overtime pay, said Muresianu. “But there are ways you could mitigate the damage.”

Personal Finance

How top tax rates compare, as Trump eyes hike for wealthy

Published

1 day agoon

May 9, 2025

U.S. President Donald Trump points as he attends the annual Friends of Ireland luncheon hosted by U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., U.S., March 12, 2025.

Evelyn Hockstein | Reuters

As Republicans wrestle with funding their massive spending and tax package, President Donald Trump is eyeing a possible tax hike for the highest earners.

The idea, which lacks Republican support, could return the top federal income tax rate to 2017 levels for some of the wealthiest Americans.

In a phone call Thursday, NBC reported, Trump pressed House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., to raise the top income tax rate on the wealthiest Americans and close the so-called carried interest loophole. The proposal would revert the 37% rate to 39.6% for individuals making $2.5 million or more per year, to help preserve Medicaid and tax cuts for everyday Americans.

More from Personal Finance:

How many consumers are preparing for an economic hit

Why Americans think real estate, gold are the best long-term investments

Trump tariffs sparked ‘uptick’ in I bond interest, advisor says. What to know

Trump on Friday expressed openness to the tax hike on the wealthiest Americans in a Truth Social post, noting he would “graciously accept” the tax increase to “help the lower and middle income workers.”

“Republicans should probably not do it, but I’m OK if they do!!!” he wrote.

Enacted by Trump, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, or TCJA, of 2017 created sweeping tax breaks for individuals and businesses. Most will sunset after 2025 without an extension from Congress.

The TCJA temporarily dropped the highest income tax rate from 39.6% to 37%. For 2025, the 37% rate kicks in for single filers once taxable income exceeds $626,350.

How Trump’s idea compares to historic rates

If signed into law, a top 39.6% income tax rate would return wealthy taxpayers to pre-TCJA levels from 2013 to 2017. Before that, the top rate was 35% during most of the early 2000s, according to data collected by the Tax Policy Center. The highest top rate was 94% from 1944-1945.

However, this data doesn’t reflect how much income was subject to top rates or the value of standard and itemized deductions during these periods, the organization noted.

Trump’s tax package faces a ‘math issue’

With control of Congress, Republicans can pass legislation through a process known as “reconciliation,” which can sidestep the Senate filibuster with a simple majority.

However, there’s still disagreement about what should be included in the multi-trillion-dollar bill and how to finance it.

Lawmakers face “a pretty simple math issue,” with many proposals not covering the cost, Yale Budget Lab president and law professor Natasha Sarin told CNBC’s “Squawk Box” on Friday.

“We’re not getting anywhere close to the type of revenue increases we need,” she said.

Personal Finance

Real estate and gold vs. stocks: Best long-term investment

Published

2 days agoon

May 9, 2025

Brendon Thorne | Bloomberg | Getty Images

Some Americans believe real estate and gold are the best long-term investments. Advisors think that’s misguided.

About 37% of surveyed U.S. adults view real estate as the best investment for the long haul, according to a new report by Gallup, a global analytics and advisory firm. That figure is roughly unchanged from 36% last year.

Gold was the second-most-popular choice, with 23% of surveyed respondents. That’s five points higher than last year.

To compare, just 16% put their faith in stocks or mutual funds as the best long-term investment — a decline of six percentage points from 2024’s report, Gallup found.

The firm polled 1,006 adults in early April.

More from FA Playbook:

Here’s a look at other stories impacting the financial advisor business.

Financial advisors caution that this preference is likely more about buzz than fundamentals. Be careful about getting caught up in the hype, said certified financial planner Lee Baker, the founder, owner and president of Claris Financial Advisors in Atlanta.

Carolyn McClanahan, a CFP and founder of Life Planning Partners in Jacksonville, Florida, agreed: “People are always chasing what’s hot, and that’s the stupidest thing you could do.”

Here’s what investors need to know about gold and real estate, and how to incorporate them in your portfolio.

Why gold and real estate are alluring

Baker understands why people like the idea of real estate and gold: Both are tangible objects versus stocks.

“You buy a house, you can see it, feel it, touch it. Your investment in stocks perhaps doesn’t feel real,” said Baker, a member of CNBC’s Financial Advisor Council.

While the preference for gold grew this year, the share of Gallup respondents who think it’s the best long-term investment is still below the record high of 34% in 2011. Back then, gold investors sought refuge amid high unemployment, a crippled housing market and volatile stocks, Gallup noted.

Gold prices have been trending upward this spring. Spot gold prices hit an all-time high of above $3,500 per ounce in late April. One year ago, prices were about $2,200 to $2,300 an ounce.

Real estate has also drawn more interest in recent years amid high demand from buyers and accelerating prices. The median sale price for an existing home in the U.S. in March was $403,700, according to Bankrate. That is down from the record high of $426,900 in June.

Why stocks are the better bet

While real estate and gold are two assets that can appreciate in value over time, the stock market will generally grow at a much higher rate, experts say.

The annualized total return of S&P 500 stocks is 10.29% over the 30-year period ending in April, per Morningstar Direct data. Over the same time frame, the annualized total return for real estate is 8.78% and for gold, 7.38%.

McClanahan also points out that unlike gold and real estate, stocks are diversified assets, meaning you’re spreading out your cash versus concentrating it into one investment.

“When you talk about stocks, you’re not talking about one big asset,” she said. “You’re talking about thousands and thousands of companies that do different things.” McClanahan is also a member of the CNBC FA Council.

While the tangibility of gold and real estate may provide a sense of comfort, it also makes them illiquid, or difficult to cash out, McClanahan said.

How to include gold, real estate into your portfolio

If you are among the Americans that want exposure to real estate or gold, there are different ways to do it wisely, experts say.

For real estate, financial advisors say investors might look into real estate investment trusts, also known as REITs, or consider investments that bundle real estate stocks, like exchange-traded funds.

An REIT is a publicly traded company that invests in different types of income-producing residential or commercial real estate, such as apartments or office buildings.

In many cases, you can buy shares of publicly traded REITs like you would a stock, or shares of a REIT mutual fund or exchange-traded fund. REIT investors typically make money through dividend payments.

Real estate mutual funds and exchange-traded funds will typically invest in multiple REITs and in the real estate market broadly. It’s even more diversified than investing in a single REIT.

Either way, you’re exposed to real estate without concentrating into a single property, and it will help diversify your portfolio, McClanahan said.

Similar to gold — instead of stocking up on gold bullions, consider investing in gold through ETFs.

That way you avoid having to deal with finding a place to store or hide physical gold, you wash off the stress of it getting stolen or making sure it’s covered by your home insurance policy, experts say.

“With the ETF, you actually get the value of the return of gold, but you don’t actually own it,” McClanahan said.

Essential Strategies for Maintaining Data Security in Modern Bookkeeping

Investor Ric Edelman reacts to crypto ETF boom

The key issues and who stands to benefit

New 2023 K-1 instructions stir the CAMT pot for partnerships and corporations

The Essential Practice of Bank and Credit Card Statement Reconciliation

Are American progressives making themselves sad?

Trending

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoWarren Buffett to ask board to make Greg Abel CEO of Berkshire Hathaway at year-end

-

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week agoMillions of older workers lost jobs during Covid. Prospects have improved

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoBerkshire meeting ‘bazaar’ features Buffett Squishmallows, 60th anniversary book and giant claw machine

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoWhy does America have birthright citizenship?

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoHow Donald Trump could rescue John Roberts

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoJobs report Friday to provide important clues on where the economy is heading

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoHow one Ivy League university avoided the president’s wrath

-

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week agoThe Importance of Backing Up Bookkeeping Data