In today’s fast-paced business world, having clear and organized documentation for your bookkeeping processes is more important than ever. Whether you’re running a small business or managing the finance team of a growing organization, well-documented bookkeeping procedures help maintain consistency, reduce errors, and ensure smooth financial operations. From training new employees to passing audits with ease, proper documentation is a key part of strong financial management. This guide explores the best practices for documenting bookkeeping processes and how it can support your business’s long-term financial health.

Why Documenting Bookkeeping Processes Matters

Creating detailed bookkeeping documentation helps ensure that every task, no matter how small, is performed consistently. It provides a reference point for team members and serves as a safeguard against the loss of institutional knowledge. Without it, businesses risk financial disorganization, mistakes in reporting, and delayed month-end closings. Solid documentation also simplifies training, allowing new hires to get up to speed faster and with fewer questions.

Create a Central Bookkeeping Manual

Start by building a centralized bookkeeping procedures manual. This should be a master document that outlines all your financial processes in one place. Include a detailed table of contents to make navigation simple, and break the manual into clearly labeled sections for tasks like bank reconciliations, accounts payable, payroll, and tax reporting. A centralized manual becomes the go-to resource for any bookkeeping-related question.

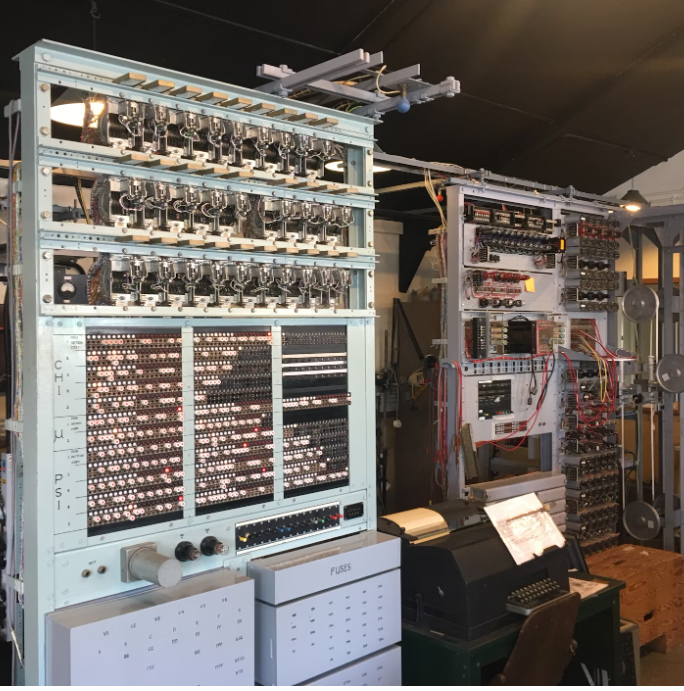

Use Visual Aids for Clarity

Not everyone learns by reading paragraphs of instructions. That’s where flowcharts and visual aids come in. Use diagrams to map out processes such as invoice approvals, payroll workflows, or monthly closing checklists. Visual aids make it easier to understand the steps involved and how different roles or systems interact. For team members who are new or unfamiliar with a process, these visuals can dramatically reduce confusion.

Document Daily, Weekly, Monthly, and Yearly Tasks

Break your bookkeeping responsibilities into routine timeframes. Clearly list which tasks must be done daily (like updating cash receipts), weekly (such as entering bills), monthly (like closing the books), and annually (including tax filings and 1099 issuance). For each task, include step-by-step instructions and examples when possible. Using screenshots from accounting software can also help clarify what specific steps look like in action.

Be Detailed but Simple

When writing instructions, use clear, simple language. Avoid technical jargon unless it’s necessary, and always explain terms that someone new might not understand. Write your documentation at a 10th-grade reading level so that it’s accessible to everyone on your team. Assume that the reader knows nothing about the task and guide them through the process like a tutorial.

Keep a Standard Format Across All Documentation

Use a consistent format and style throughout your documentation. This means applying the same headers, fonts, bullet styles, and terminology across all sections. Consistency makes the documentation easier to read and helps users find information quickly. It also helps when you need to make updates or train team members using multiple sections of the guide.

Include Technology and Software Instructions

Because most bookkeeping is now handled with accounting software, it’s essential to include documentation for the systems you use. Explain how to log in securely, run reports, handle backups, and connect software with banks or third-party tools. Document how systems like QuickBooks, Xero, or payroll platforms are used in your workflow. Be sure to include troubleshooting tips and contact information for software support if needed.

Schedule Regular Reviews and Updates

Your financial processes will evolve as your business grows. To keep your documentation useful and relevant, set a schedule to review and update it regularly—at least once every quarter or twice a year. During these reviews, check for outdated procedures, changes in regulations, or software updates that affect how tasks are done. Encourage your team to provide feedback if they notice anything unclear or missing in the documentation.

Make Documentation Easily Accessible

It’s important that your team can access the documentation easily, whether it’s stored on a shared drive, intranet, or document management system. Don’t let it sit buried in an email folder or personal computer. Assign someone to be responsible for maintaining the documentation and ensuring everyone knows where to find it.

Build a Culture of Documentation

For documentation to be truly effective, it needs to be part of your organization’s culture. Encourage all finance and accounting team members to document their processes and contribute to improving procedures. Make it a habit to update instructions anytime a process changes or a new one is introduced.

Documentation Is a Tool for Growth

Documenting your bookkeeping processes isn’t just a best practice—it’s a smart strategy for financial organization, accuracy, and efficiency. It supports continuity, improves training, and helps your business run smoothly even during staff transitions or periods of growth. With clear and updated documentation, your business will be better prepared to handle audits, close the books on time, and make informed financial decisions. Investing time in creating strong bookkeeping documentation pays off with fewer mistakes, faster processes, and a more confident team.

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics6 days ago

Economics6 days ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Blog Post6 days ago

Blog Post6 days ago

Personal Finance6 days ago

Personal Finance6 days ago

Finance6 days ago

Finance6 days ago