IN THE MIDDLE of a four-hour Supreme Court debate on February 26th over state laws regulating social-media sites, Justice Samuel Alito asked Paul Clement, the platforms’ lawyer, to imagine that “YouTube were a newspaper”. How much, Justice Alito asked, “would it weigh?” The snark was directed at Mr Clement’s suggestion that Facebook, YouTube and their ilk deserve editorial control over the content they host just as newspapers are free to decide which articles appear on their broadsheets.

If Justice Alito was sceptical of the regulators’ comparisons of platforms to telegraph companies (which must dispatch all messages, not just the ones they agree with), he was downright hostile to the newspaper analogy. But Mr Clement had a rejoinder: a paper version of YouTube “would weigh an enormous amount, which is why, in order to make it useful, there’s actually more editorial discretion going on in these cases” than in any of the others that have come before the court.

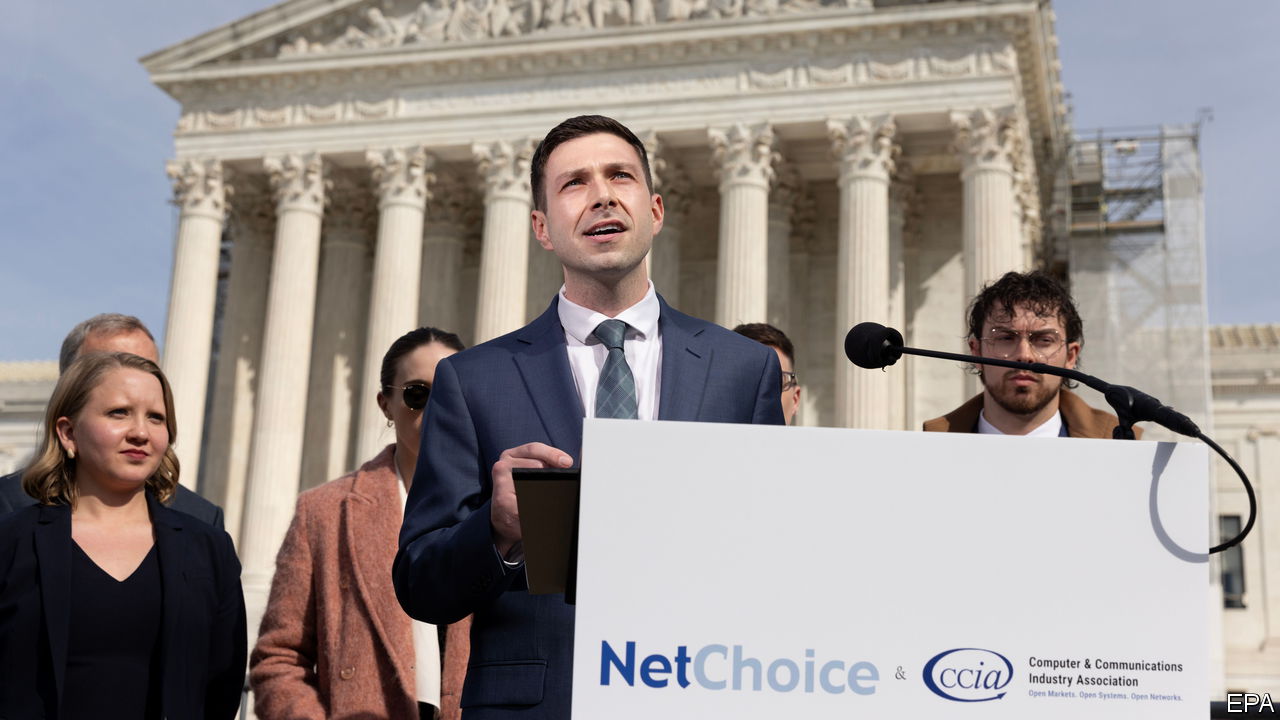

The laws at issue date from 2021, when Republican legislatures in Florida and Texas sought to rein in sites like Facebook and Twitter because they had sidelined anti-vaccine activists and insurrectionists (including a user named Donald Trump). Two industry groups—NetChoice and the Computer & Communications Industry Association—quickly sued. Governments cannot constitutionally wrest control of content-moderation from private companies, they argued. After the appellate courts asked to consider the cases split on the question, Moody v NetChoice and NetChoice v Paxton arrived at the Supreme Court.

Justice Alito’s sympathies seemed to lie with Florida and Texas, as did those of Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch. The three mused that content moderation is a euphemism for “censorship”, prompting Mr Clement to insist that only the government can properly be said to “censor”. The three also accused the social-media sites of trying to have their cookies and eat them too. In last year’s cases involving Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, the companies said they should be immune from liability for dangerous content on their sites; but now they claim to exercise editorial discretion. There’s no double standard, Mr Clement explained in response. An anthologist may decide which short stories to include in a collection but is not herself author of any of the stories.

Mr Clement and Elizabeth Prelogar, President Joe Biden’s solicitor-general, may not have persuaded the most conservative wing of the court to side with the social-media platforms, but five or six justices were worried that the treatment of the companies by Florida and Texas threatened their First Amendment freedoms. Justice Brett Kavanaugh noted the “Orwellian” nature of a state that endeavours to “[take] over media”. The court’s precedents have clarified, he said, “that we have a different model here” and it is not one of “the state interfering with…private choices”.

John Roberts, the chief justice, echoed this sentiment, noting that the court’s “first concern” should be protecting the “modern public square” from state meddling. Justice Sonia Sotomayor voiced concern over laws “that are so broad that they stifle speech”. And Justice Elena Kagan discussed the public utility of sites that quell “misinformation” about voting and public health and filter out hate speech.

If the Supreme Court lets the laws take effect, Mr Clement argued, those priorities would be thrown out of the window. Social-media sites will lose their charm—and worse. With no ability to take down posts based on their ‘”viewpoint”, platforms would have to open their servers to debates they will rue. If you have to be viewpoint-neutral, he said, permitting users to post about suicide-prevention would entail allowing advocacy of suicide-promotion, too. Or “pro-Semitic” posts would mean you’re equally open to antisemitic views. “This is a formula”, he concluded, “for making these websites very unpopular to both users and advertisers.”

Yet worries from a majority of the court about what Ms Prelogar called the laws’ “very clear defect” may not suffice to give what Justice Alito dubbed the “megaliths” of social media a clean win. That’s because Florida’s law, at least, seems sloppily drafted enough to apply not just to giant platforms such as Facebook and YouTube but to e-commerce sites such as Etsy, Uber and Venmo. And NetChoice was seeking to get the laws thrown out entirely rather than merely narrowing their focus.

But, as Justice Kagan pointed out, Florida’s law seems to have a “plainly legitimate sweep”—applications that do not violate the First Amendment because they regulate not speech but conduct (requiring an Uber driver to pick up Republicans as well as Democrats, say). Those constitutional (if not so salient) corners of the law may be enough to thwart the effort to ditch them. A messy consensus seemed to emerge: send the cases back to the lower courts to sort out all the facts. Which means a year or two down the road, the justices may find themselves clicking refresh. ■

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Blog Post1 week ago

Blog Post1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance7 days ago

Personal Finance7 days ago

Personal Finance7 days ago

Personal Finance7 days ago

Economics7 days ago

Economics7 days ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago