“General Hospital” has the distinction of running longer than any soap opera in American television history. Yet the months-long budget melodrama in Washington, DC, which mercifully concluded on March 23rd, at times felt destined to become almost as much of a fixture of American life as the medical serial that debuted in 1963.

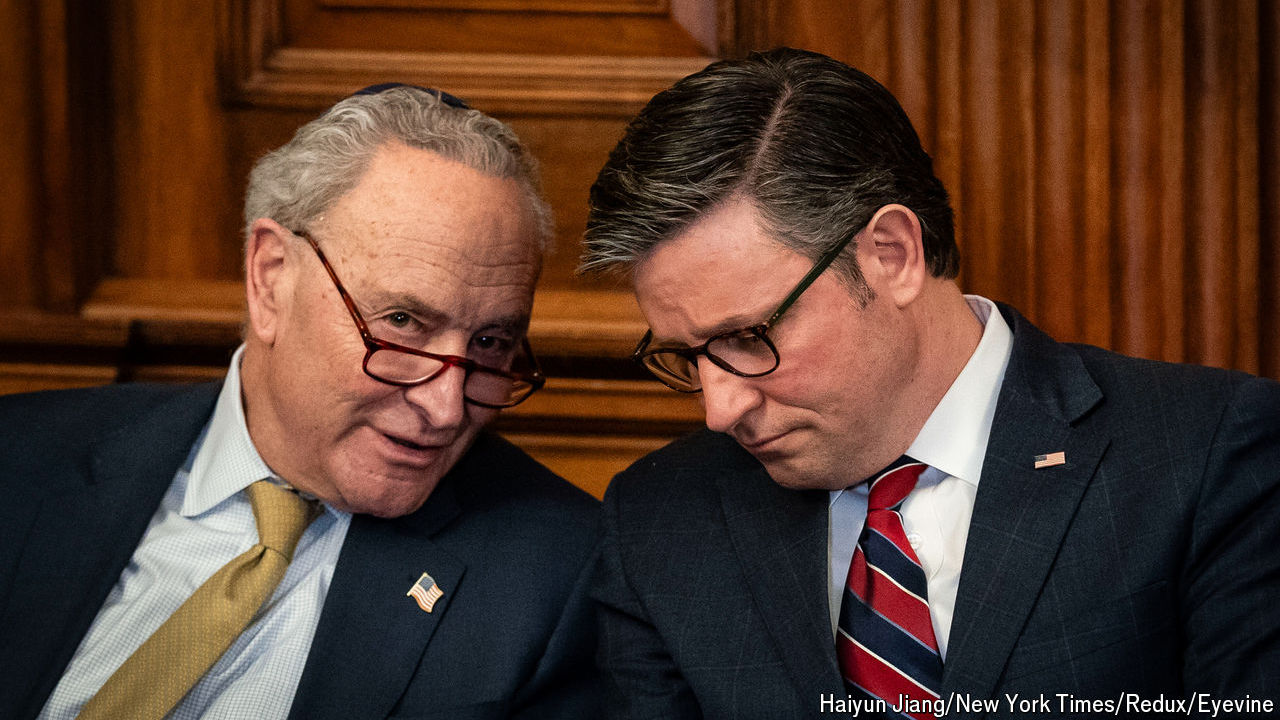

The 2024 fiscal year began nearly six months ago, but only now has Congress managed to pass a long-term budget deal to fully fund the federal government through the remainder of the fiscal year. Kevin McCarthy was ousted as House speaker in October 2023 after preventing a lapse in government funding. Mike Johnson, his successor, allowed three more “continuing resolutions” to avoid unnecessary government shutdowns, but the delays culminated in an agreement that differed little from what the White House and Congress had agreed to in principle nearly a year ago.

The $1.2trn package just passed covers about 75% of government spending. (The remainder already had been authorised in a bill signed into law earlier in the month.) The latest legislation cleared the Republican-controlled House on Friday March 22nd on a 286-134 vote, while the Democrat-led Senate approved it, after much last-minute haggling, in the early hours of Saturday morning, by 74-24. The bill, more popular with Democrats than Republicans, marginally reduces government spending but on its own won’t significantly alter America’s fiscal destiny.

“It’s good to see Congress put something in place to control spending levels for one year,” says Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a bipartisan non-profit group. That doesn’t mean members of Congress should be patting themselves on the back. “There’s so much more to be done, and they are all the things that politicians are saying they won’t do, including raising taxes, fixing Social Security and fixing Medicare.”

Underperformance has never prevented legislators from claiming victory anyway. Democrats and Republicans alike will be happy to take credit for a 5.2% salary increase for military personnel, and even some Republicans can applaud 12,000 new special immigrant visas for American allies in Afghanistan attempting to flee Taliban rule. The bill also includes policy prizes that fall under neater partisan categories.

Mr Johnson won new money for Immigration and Customs Enforcement to expand immigration-detention capacity and pay for 22,000 border-patrol agents. Republicans also secured a one-year ban on funding for the UN Relief and Works Agency, which provides aid to Palestinian refugees, along with a 6% reduction in broader spending on foreign programmes. All are real wins for a party increasingly supportive of Israel, sceptical of immigration and isolationist in its global outlook.

Democrats, however, blocked a host of other policies popular among Republicans, such as anti-abortion provisions. Members of Mr Biden’s party are also touting $1bn for a climate-change programme at the Pentagon and another $1bn for child care and Head Start, an education programme for young children from poor families. This mixed outcome in any deal ought to be expected, given America’s divided government, but Republican hardliners were not impressed.

Chip Roy, a congressman from Texas, acknowledged after the bill was released that Republicans would not get everything they wanted when Democrats controlled the White House and Senate. He opposed the measure regardless. “Any Republican who votes for this bill OWNS the murders, the rapes and the assaults by the people that are being released into our country,” Mr Roy said, citing its insufficiently harsh immigration provisions. “A vote for this bill is a vote against America.”

Mr McCarthy lost his job after years of enduring this sort of over-the-top rhetorical abuse, but his replacement has largely followed his lead. The final deal had been negotiated behind closed doors between Mr Biden’s team and congressional leaders. Mr Johnson listened to the hardline Freedom Caucus, to which Mr Roy belongs, but ultimately ignored the group. To avoid a government shutdown, he even ignored a rule that previously required the House not vote on a bill until 72 hours after its text was released.

As a relatively unknown congressman, Mr Johnson was one of the most conservative members of the lower chamber. He is still deeply conservative, but the price of power is recognising the need to compromise. The provisions in this bill will expire at the end of September, weeks before the presidential election. In all likelihood a short-term spending bill will be cobbled together to carry legislators through campaign season, to avoid a messy spending fight just as Americans get ready to vote.

For now, Mr Johnson has said that he would turn his focus to providing aid for Israel, Taiwan and Ukraine. He previously declined to take up a Senate bill that paired military assistance with immigration reform, and some members of the House are working on a strategy to force a vote on the issue. If Mr Johnson supported assistance for Ukraine after cutting a deal with Democrats, could he meet the same fate as Mr McCarthy?

Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican congresswoman from Georgia, filed a “motion to vacate” the speakership after the legislation passed, calling it a “warning”. There is no guarantee that the resolution will be taken up, and Mr Johnson appears more secure than Mr McCarthy did before his fall in October. “The funny thing is that the reason he might survive is that there’s no one else,” says Yuval Levin of the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think-tank. “This job, which is normally pretty desirable, is so undesirable that nobody wants to fire the current guy, because nobody wants to take it.”■

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago