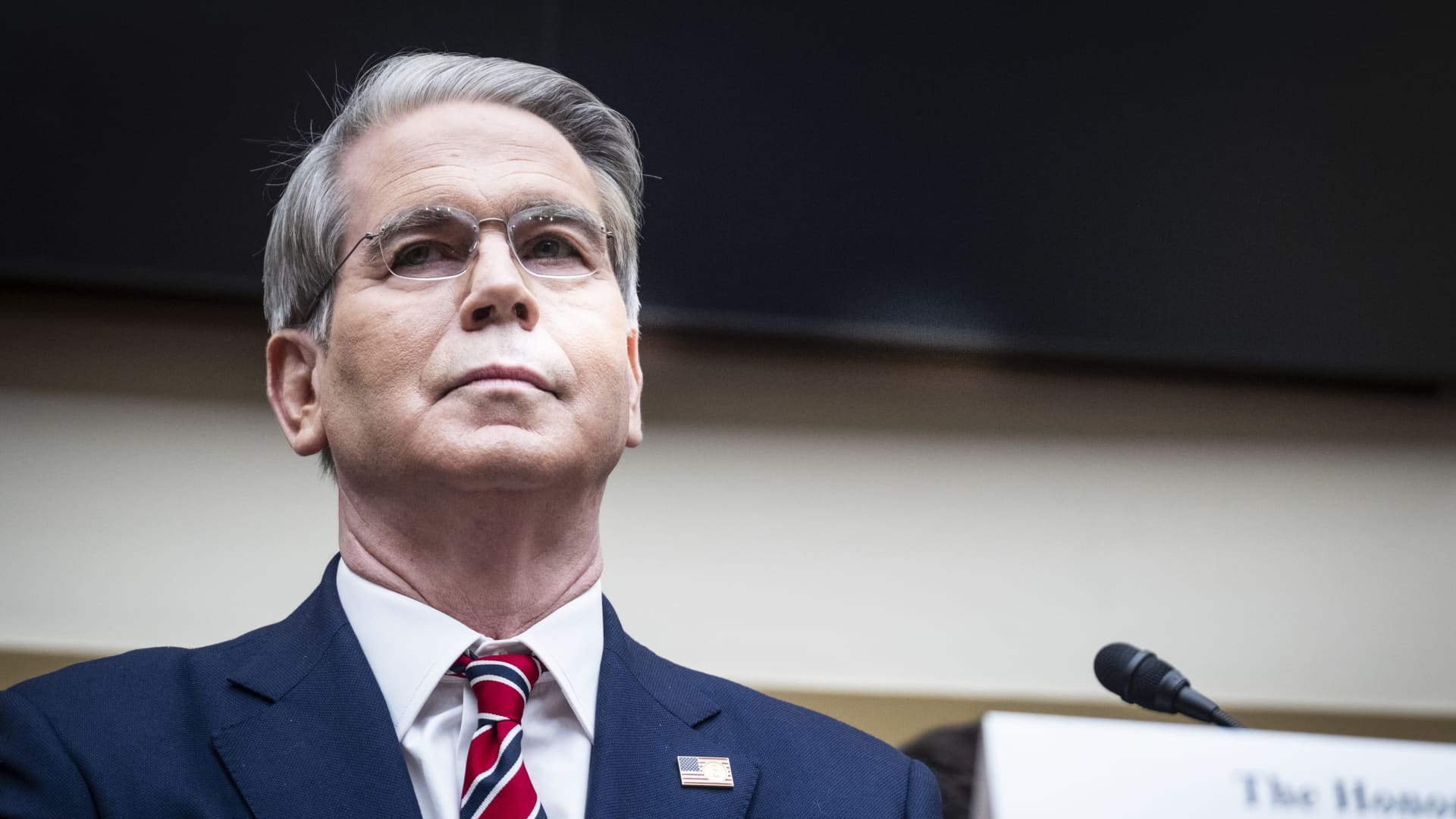

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said in an interview on NBC News’ “Meet the Press” that Moody’s Ratings were a “lagging indicator” after the group downgraded the U.S.’ credit rating by a notch from the highest level.

“I think that Moody’s is a lagging indicator,” Bessent said Sunday. “I think that’s what everyone thinks of credit agencies.”

Moody’s said last week that the downgrade from Aaa to Aa1 “reflects the increase over more than a decade in government debt and interest payment ratios to levels that are significantly higher than similarly rated sovereigns.”

The treasury secretary asserted that the downgrade was related to the Biden administration’s spending policies, which that administration had touted as investments in priorities, including combatting climate change and increasing health care coverage.

“Just like Sean Duffy said with our air traffic control system, we didn’t get here in the past 100 days,” Bessent continued, referring to the transportation secretary. “It’s the Biden administration and the spending that we have seen over the past four years.”

The U.S. has $36.22 trillion in national debt, according to the Treasury Department. It began growing steadily in the 1980s and continued increasing during both President Donald Trump’s first term and former President Joe Biden’s administration.

Bessent also told moderator Kristen Welker that he spoke on the phone with the CEO of Walmart, Doug McMillon, who the treasury secretary said told him the retail giant would “eat some of the tariffs, just as they did in ’18, ’19 and ’20.”

Walmart CFO John David Rainey previously told CNBC that Walmart would absorb some higher costs related to tariffs. The CFO had also told CNBC separately that he was “concerned” consumers would “start seeing higher prices,” pointing to tariffs.

Trump said in a post to Truth Social last week that Walmart should “eat the tariffs.” Walmart responded, saying the company has “always worked to keep our prices as low as possible and we won’t stop.”

“We’ll keep prices as low as we can for as long as we can given the reality of small retail margins,” the statement continued.

When asked about his conversation, Bessent denied he applied any pressure on Walmart to “eat the tariffs,” noting that he and the CEO “have a very good relationship.”

“I just wanted to hear it from him, rather than second-, third-hand from the press,” Bessent said.

McMillon had said on Walmart’s earnings call that tariffs have put pressure on prices. Bessent argued that companies “have to give the worst case scenario” on the calls.

The White House has said that countries are approaching the administration to negotiate over tariffs. The administration has also announced trade agreements with the United Kingdom and China.

Bessent said on Sunday that he thinks countries that do not negotiate in good faith would see duties return to the rates announced the day the administration unveiled across-the-board tariffs.

“The negotiating leverage that President Trump is talking about here is if you don’t want to negotiate, then it will spring back to the April 2 level,” Bessent said.

Bessent was also asked about Trump saying the administration would accept a luxury jet from Qatar to be used as Air Force One, infuriating Democrats and drawing criticism from some Republicans as well.

The treasury secretary called questions about the $400 million gift an “off ramp for many in the media not to acknowledge what an incredible trip this was,” referring to investment commitments the president received during his trip last week to Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

“If we go back to your initial question on the Moody’s downgrade, who cares? Qatar doesn’t. Saudi doesn’t. UAE doesn’t,” he said. “They’re all pushing money in.”

When asked for his response to those who argue that the jet sends a message that countries can curry favor with the U.S. by sending gifts, Bessent said that “the gifts are to the American people,” pointing to investment agreements that were unveiled during Trump’s Middle East trip.

Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., criticized Bessent’s comments about the credit downgrade, saying in a separate interview on “Meet the Press.”

“I heard the treasury secretary say that, ‘Who cares about the downgrading of our credit rating from Moody’s?’ That is a big deal,” Murphy said.

“That means that we are likely headed for a recession. That probably means higher interest rates for anybody out there who is trying to start a business or to buy a home,” he continued. “These guys are running the economy recklessly because all they care about is the health of the Mar-a-Lago billionaire class.”

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Economics5 days ago

Economics5 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago