Economics

Why half of America will vote for Donald Trump

Published

6 months agoon

DONALD TRUMP has dominated the American right for nine years and yet, even after a decade of study, many observers still cannot fathom why. But voters are certainly not tired of Mr Trump. Even after the scandal and mayhem of his first term, culminating in his attempt to cling to power after losing the election in 2020, around half of the electorate, or some 75m Americans, will vote for him this time.

What accounts for his enduring strength? At first it was common on the left to point to racism, misogyny and xenophobia, sustained by misinformation and lies. Hillary Clinton infamously summarised this thesis. “To just be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump’s supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables,” she once said.

The early explanations from Mr Trump’s sympathisers could be equally simplistic and hysterical. In 2016 Michael Anton made the most prominent intellectual case for Mr Trump. He wrote that Americans needed to register a populist primal scream before their way of life was permanently extinguished, and called 2016 the “Flight 93 election” (referring to the plane hijacked on September 11th 2001 that crashed in a field in Pennsylvania after a passenger revolt). Mr Anton elaborated: “A Hillary Clinton presidency is Russian Roulette with a semi-auto. With Trump, at least you can spin the cylinder and take your chances.” Most Americans did not think 2016 was a Flight 93 election. In fact, 40% of eligible voters didn’t bother to express an opinion.

Calmer analysis is more helpful. Social scientists provide three kinds of explanation. Political scientists point out the importance of institutions; political economists put stress on material conditions; and political sociologists emphasise the cultural divide between elites and the self-described populus.

The first explanation, the political-science one, sees Mr Trump as a lucky beneficiary, or perhaps even a canny exploiter, of America’s peculiar political system. First-past-the-post voting, which awards elections to the candidate who commands a plurality, encourages a two-party duopoly. (When Mr Trump applied his talents to seek the nomination of the Reform Party in 2000, it did not end well.) Open primary elections have meant that rank-and-file members wield more power than party elites when selecting the presidential nominee. That allows a faction, as the Make America Great Again crowd could be called, to seize control of a major-party apparatus if it is successful enough.

Democrats had their own insurrectionary movements from the populist left in both 2016 and 2020, led by Bernie Sanders and then by Elizabeth Warren. But neither of them managed to capture the consistent 25-35% of primary voters that Mr Trump did in the early Republican primaries in 2016. Were European-style multiparty democracy to be transplanted to America, a Trump-led MAGA party might draw a lot of support without attracting a majority—like the hard-right Alternative for Germany.

Once in charge of the party, the two-party system works in favour of the rebellious faction, forcing co-partisans to make their peace with the new leadership. This explains a lot of Mr Trump’s support now. But the political-systems approach is less satisfying as an explanation for why his hold is so enduring, making him the first person to win a major party’s nomination three times in a row since Franklin Roosevelt.

Political economy—explanation number two—could throw light on part of this longevity. The American economy boomed during Mr Trump’s first term in office, up until the covid-19 pandemic. Although voters did not approve of Mr Trump’s conduct in office, and especially on January 6th 2021, when his supporters violently breached the Capitol, their anger over inflation and pessimism over the economy are pushing them to rebuke the incumbent Democrats, to the benefit of Mr Trump.

Evidence from outside America suggests there is a lot to this. Voters are in an anti-incumbent mood everywhere, rejecting the ruling parties in Britain, France, India and Japan (and presumably next year in Canada and Germany). But the idea that the economy is making people cross does not fit with what’s actually happening in America. The gap in output per person between Canada, western Europe and Japan on one side and America on the other has doubled since 1990. America’s economy is the envy of the world, with fast increases in real wages for the poorest workers. If inequality is the cause, that is hard to square with data showing wages rising in “left-behind” places and no increase in income inequality in the past decade.

That leaves a third genre of explanation: political sociology. Even though American politics has remained almost perfectly divided over the past decade, it has not been static. Voters are less divided by income or race than before; instead a striking new dividing line is educational class. Democrats increasingly attract the support of the professional, suburban managerial class who find Mr Trump repulsive and unfit for office; the working classes, including an increasing share of the non-white working class, admire that Mr Trump has made the right enemies, talks like them, talks to them, and promises them a future in which they receive dignity and their just financial desserts—even if they know that these promises are unlikely to be kept.

Visiting an area in North Carolina hit hard by flooding a few weeks ago, Mr Trump promised that under his rule every property that had been destroyed would be rebuilt, and more beautifully than before. Never mind that some of them are in areas prone to flooding and so will not be rebuilt. It was what people wanted to hear. One speaker who welcomed Mr Trump described his visit as the shot in the arm of hope that people needed, and said his visit guaranteed that people there would not be forgotten. To use the language of pop psychology, Mr Trump makes a lot of Americans feel seen. That he is happy to dress up in the uniform of a McDonald’s worker or a garbage-truck guy, despite being worth several billion dollars, helps too. Kamala Harris, who actually worked at McDonalds, seems to cringe at such stuff.

The realignment according to educational qualifications means that the most serious divide in America is over culture rather than money. Under Mr Trump, the Republican Party looks increasingly left-labour in its economics, advocating protectionism, working-class tax giveaways and preservation of the existing entitlement system. To many Americans without a college degree, Democrats no longer talk to them but down to them. That is why, despite being showered with dollars from the federal government under President Joe Biden, members of America’s industrial unions are moving towards Mr Trump this year. And it is why the Trump campaign seized on remarks by a befuddled Mr Biden a few days ago, in which he appeared to call Trump supporters “garbage”. “See: Democrats still think you are deplorables,” was their message.

Democrats—and a good number of former members of the Republican elite—genuinely wonder how it is that Mr Trump’s supporters so quickly dismiss his efforts to overturn a democratic election, or his poor record of achievement on policy in office, or the undermining of abortion rights which he engineered. Mr Trump’s supporters see these criticisms as overhyped. And they see them as hypocritical, pointing out that the legal system has in fact been weaponised against Mr Trump in a way that he merely threatens.

Culture means Democrats and Republicans live in different countries. Tens of millions of Trump voters (mistakenly) believe America is in a recession. They think Democrats brought on inflation when they managed the economy, which boomed under Trumponomics. They observe that there were no new wars launched when Mr Trump was in the White House. Under Mr Biden’s watch, there are security crises in the Middle East and Ukraine. Trumpism is a simple heuristic, just as Trump-loathing is. It could be powerful enough to take him back to the White House.

You may like

-

Americans are getting flashbacks to 2008 as tariffs stoke recession fears

-

Trump insists bond market tumult didn’t influence tariff pause: ‘I wasn’t worried’

-

Orders for big-ticket items like autos and appliances surged 9.2% in March in rush to beat tariffs

-

German finance minister prefers zero for zero tariff solution

-

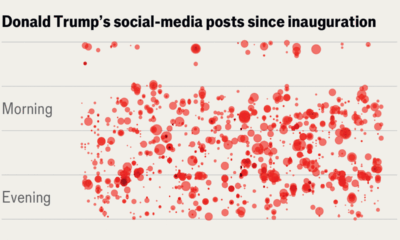

America’s poster-in-chief is very, very online

-

Donald Trump hopes to become a one-man deregulator

Economics

Americans are getting flashbacks to 2008 as tariffs stoke recession fears

Published

1 hour agoon

April 26, 2025

Homemade barbecue pork chops. Katy Perry performs onstage during the Katy Perry The Lifetimes Tour 2025. A woman checks her receipt while exiting a store.

iStock| Theo Wargo | Hispanolistic | Getty Images

A few weeks ago, as Kiki Rough felt increasingly concerned about the state of the economy, she began thinking about previous periods of financial hardship.

Rough thought about the skills she learned about making groceries stretch during the tough times that accompanied past economic downturns. Facing similar feelings of uncertainty about the country’s financial future, she began making video guides to recipes from cookbooks published during previous recessions, depressions and wartimes.

The 28-year-old told followers that she is not a professional chef, but instead earned her stripes by learning to cook while on food stamps. From Rough’s yellow-and-black kitchen in the Chicago suburbs, she teaches viewers how to make cheap meals and at-home replacements for items like breakfast strudel or donuts. She often reminds people to replace ingredients with alternatives they already have in the pantry.

“I keep seeing this joke over and over in the comments: The old poors teaching the new poors,” Rough told CNBC. “We just need to share knowledge right now because everyone is scared, and learning is going to give people the security to navigate these situations.”

The self-employed consultant’s videos quickly found an audience on TikTok and Instagram. Between both platforms, she’s gained 350,000 followers and garnered about 21 million views on videos over the last month, by her count.

President Donald Trump’s announcement of broad and steep tariffs earlier in April has ratcheted up fears of the U.S. economy tipping into a recession in recent weeks. As Americans like Rough grow increasingly worried about the road ahead, they are harking back to the tips and tricks they employed to scrape by during dark financial chapters like the global financial crisis that exploded in 2008.

Google is predicting a spike in search volumes this month for terms related to the recession that came to define the late 2000s. Searches for the “Global Financial Crisis” are expected to hit levels not seen since 2010, while inquiries for the “Great Recession” are slated to be at their highest rate since the onset of the Covid pandemic.

Porkchops, house parties and jungle juice

On TikTok, a gaggle of Millennials and Gen Xers has stepped into the roles of older siblings, offering flashbacks and advice to younger people on how to pinch pennies. Some Gen Zers have put out calls to elders for insights on what a recession may feel like at this stage of life, having been too young to feel the full effects of the financial crisis.

“This is, potentially, at least on a large scale, the first time that millennials have been able to be the ‘experts’ on something,” said Scott Sills, a 33-year-old marketer in Louisiana. “We’re the experts on getting the rug pulled out from under us.”

Those doling out the advice are taking a trip down memory lane the to tail-end of the aughts. Cheap getaways to Florida were the norm instead of lush trips abroad. They had folders for receipts in case big-ticket purchases went on sale later. Business casual outfits were commonplace at social events because they couldn’t afford multiple styles of clothing.

Porkchops were a staple dinner given their relative affordability, leading one creator to declare that they “taste like” the Great Recession. They drank “jungle juice” at house parties, a concoction of various cheap liquors and mixers, instead of cocktails at bars.

“There’s things that I didn’t realize were ‘recession indicators’ the first time around that I thought were just the trends,” said M.A. Lakewood, a writer and professional fundraiser in upstate New York. “Now, you can see it coming from 10 miles away.”

Customers shop for produce at an H-E-B grocery store on Feb. 12, 2025 in Austin, Texas.

Brandon Bell | Getty Images

To be sure, some of the discourse has centered around how inflationary pressures have made a handful of these hacks defunct. Some content creators pointed out that the federal minimum wage has sat at $7.25 per hour since 2009 despite the cost of living skyrocketing.

Kimberly Casamento recently began a TikTok series walking viewers through recipes from a cookbook that was focused on affordable meals published in 2009. The New Jersey-based digital media manager said she’s found costs for what were then considered low-budget meals ballooning between about 100% and 150%. In addition to sharing the price changes, the 33-year-old gives viewers some tips on how to keep costs down.

“Every aspect of life is so expensive that it’s hard for anybody to survive,” Casamento said. “If you can cut the cost of your meal by $5, then that’s a win.”

‘A very human thing’

This type of communal knowledge-sharing is common during times of economic belt tightening, according to Megan Way, an associate professor at Babson College who studies family and intergenerational economics. While conversations about how to slash costs or to make meals stretch typically took place among neighbors in the late 2000s, Way said it makes sense that they would now play out in the digital square with the rise of social media.

“It’s a very human thing to reach out to others when things are feeling uncertain and try to gain on their experience,” Way said. “It can really make a difference for feeling like you’re moving forward a little prepared. One of the worst things for an economy is absolute fear.”

Read more CNBC analysis on culture and the economy

Way said that Americans are quick to look back to the Great Recession for a guide because that downturn was so shocking and widely felt. However, she said there’s key differences between that economic situation and what the U.S. is facing today, such as the absence of bad debt that sparked the housing market’s crash.

Still, she said there’s broad uncertainty felt today on several fronts — be it tied to the economy, geopolitics or domestic policy priorities like slashing the federal workforce or limiting immigration. That can reignite the feeling of unpredictability about what the future will bring that was paramount during the Great Recession, Way said.

In 2025, it’s clear that economic confidence among the average American is rapidly souring. The University of Michigan’s index of consumer sentiment recorded one of its worst readings in more than seven decades this month.

With that negative economic outlook comes rising stress. When Lukas Battle made a satirical TikTok about feeling like divorces were increasingly common around the time of the Great Recession, the 27-year-old’s comments were abuzz with people talking about their parents splitting recently. (Though divorce has been seen as a cultural hallmark of the financial crisis, data shows the rate actually declined during this period.)

“There’s a second round of divorces happening as we speak,” Battle said.

Cultural parallels

That’s one of several parallels social media users have drawn between the late aughts and today. When videos surfaced of a group dancing to Doechii’s hit song “Anxiety,” several commenters on X reported feeling déjà vu to when flashmob performances were common.

Disney‘s reboot of the animated show “Phineas and Ferb,” which originally premiered in the late 2000s, similarly put the era top of mind.

Lady Gaga performing at Coachella 2017

Getty Images | Christopher Polk

“Recession pop,” a phrase mainly referring to the subgenre of trendy music that dropped during the Global Financial Crisis, has caught a second wave over the past year as Americans contended with inflation and high interest rates.

Now, in 2025, as the chorus of voices projecting a recession ahead grows, pop music has some familiar sounds.

In 2008, artists such as Miley Cyrus, Lady Gaga and Katy Perry regularly appeared on the music charts. Both Cyrus and Gaga have released new songs this year. Perry kicked off a world tour this week.

“It’s almost a permission to feel good, whether that’s through song or something,” said Sills, the marketer in Louisiana. “It’s not necessarily ignoring the problems that are here, but just maybe finding some sort of joy or fun in the midst of all of it.”

Economics

Checks and Balance newsletter: Predictions for the Democrats’ future

Published

2 hours agoon

April 26, 2025

Checks and Balance newsletter: Predictions for the Democrats’ future

Economics

ECB members say inflation job nearly done but tariff risks loom

Published

1 day agoon

April 25, 2025

Guests and attendeess mingle and walk through the atrium during the IMF/World Bank Group Spring Meetings at the IMF headquarters in Washington, DC, on April 24, 2025.

Jim Watson | Afp | Getty Images

After years dominated by the pandemic, supply chains, energy and inflation, there was a new topic topping the agenda at the World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s Spring Meetings this year: tariffs.

The IMF set the tone by kicking off the week with the release of its latest economic forecasts, which cut growth outlooks for the U.S., U.K. and many Asian countries. While economists, central bankers and politicians have been engaged in panels and behind-the-scenes talks, many are attempting to work out whether trade tensions between China and the U.S. are — or perhaps are not — cooling.

Policymakers from the European Central Bank that CNBC spoke to this week broadly stuck a dovish-leaning tone, indicating they saw interest rates continuing to fall and few upside risks to euro zone inflation. However, all stressed the current high levels of uncertainty, the need to keep monitoring data, and the high risks to the growth outlook — sentiments also echoed by Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey in his interview with CNBC on Thursday.

These were some of the main messages from ECB members this week.

Christine Lagarde, European Central Bank president

On inflation and monetary policy:

“We’re heading towards our [inflation] target in the course of 2025, so that disinflationary process is so much on track that we are nearing completion. But we have the shocks, you know, and the shocks will be a dampen on GDP. It’s a negative shock to demand.”

“The net impact on inflation will depend on what countermeasures are eventually taken by Europe. Then we have to take into account the [German] fiscal push by the defense investments, by the infrastructure fund.”

“We have seen successive movements, you know, announcement [of U.S. tariffs], and then a pause, and then some exemptions. So we have to be very attentive… Either we cut, either we pause, but we will be data dependent to the extreme.”

On market moves:

“When we had done our projections, we anticipated that… the dollar would appreciate, the euro would depreciate. It’s not what we saw. And there have been some counter-intuitive movements in various categories.”

“The German market has obviously been shocked in a positive way by the program soon to be put in place by the German government, with a commitment to defense, with a commitment to a big fund for infrastructure development.”

Klaas Knot, The Netherlands Bank president

On tariff uncertainty:

“If I look back over the last 14 years, in the initial days of the pandemic I think that was comparable uncertainty to what we have now.”

“In the short run, it’s crystal clear that the uncertainty that is created by the unpredictability of the tariff actions by the U.S. government works as a strong negative factor for growth. Basically, uncertainty is like a tax without revenue.”

On the inflation impact:

“In the short run, we will have lower growth. We will probably also have lower inflation. As we also see, the euro is appreciating as energy prices have also come down. So together with the sort of negative factor uncertainty in the short run, it’s crystal clear that it will accelerate the disinflation.”

“But in the medium term, the inflation outlook is not all that clear. I think there are still these negative factors. But in the medium term, you might get retaliation. You might get the disruption of global value chains, which might also be inflationary in other parts of the world than the U.S. only. And then, of course, we have the fiscal policy coming in in Europe. So this is actually a time in which you need projections.”

On a June rate cut and market pricing for two more ECB rate cuts in 2025:

“I’m fully open minded. I think it’s way too early to already take a position on June, whether it would be another cut. It will fully depend on these projections.”

“I would need to see a more structured analysis of the impact on the inflation profile ahead of us, and only then can I say whether the market is pricing fair or whether I don’t.”

Robert Holzmann, Austrian National Bank governor

On the need to wait for more data and news on tariffs:

“We have not seen this uncertainty now for years… unless the uncertainty subsides, by the right decisions, we will have to hold back a number of our decisions, and hence, we don’t know yet in what direction monetary policy should be best moved.”

“Before looking at data in detail, the question is, what kind of political decisions will be taken? Is it that we will have some tariff increases? Is it that we will have strong tariff increases? Is it that we will have retribution by high counter tariffs?”

On the ECB’s April rate cut:

“I think there’s a broad consensus [on rates]. But of course, at the margin, people differ.”

“My assessment is that at this time, it wasn’t clear yet to what extent [tariff] countermeasures were being taken. Because with countermeasures in Europe, prices may have increased. Without countermeasures, quite likely the price pressure is downward. And for the time being, we don’t know yet the direction.”

On the direction of interest rates:

“I think if the recent noises about an arrangement [on trade] were to be true, in this case, quite likely it is more towards the downside than the upside with regard to prices. But this can be changed with different decisions and the result of which, we may even imagine in [the] other direction. For the time being, no, it will be down.”

“There may be further cuts this year, but the number is still outstanding.”

Mārtiņš Kazāks, Bank of Latvia governor

On opportunity from tariffs:

“With all this uncertainty and vulnerability, this is also the time of opportunities for Europe.”

“It’s a time for Europe to grasp all the aspects of being an economic superpower and becoming a really fully-fledged political and geopolitical superpower, and this requires doing all the decisions that in the past, were not carried out fully.”

“This requires political will, political guts to make those decisions, and to strengthen the European economy and assert its place in a global world.”

On market reaction to tariffs:

“So far it seems to be relatively orderly … but if one looks at the spillovers to Europe, the financial markets are working more or less fine, we haven’t seen spreads exploding or anything like that.”

“But in terms, however, of the macro scenarios, this uncertainty is extremely elevated in the sense that, given the possible outcomes, the multiple scenarios and their probabilities are very similar with the baseline [tariff] scenario.”

What student loan forgiveness opportunities still remain under Trump

Americans are getting flashbacks to 2008 as tariffs stoke recession fears

Checks and Balance newsletter: Predictions for the Democrats’ future

New 2023 K-1 instructions stir the CAMT pot for partnerships and corporations

The Essential Practice of Bank and Credit Card Statement Reconciliation

Are American progressives making themselves sad?

Trending

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoChina targets U.S. services and other areas after decrying ‘meaningless’ tariff hikes on goods

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoDonald Trump’s approval rating is dropping

-

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week agoHere’s why retirees shouldn’t fully ditch stocks

-

Blog Post7 days ago

Blog Post7 days agoDocumenting Bookkeeping Processes and Procedures

-

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week agoIRS’ free tax filing program is at risk amid Trump scrutiny

-

Economics6 days ago

Economics6 days agoDonald Trump wants a certain kind of immigrant: the uber-rich

-

Economics7 days ago

Economics7 days agoTrump’s approval rating on economy at lowest of presidential career

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago‘He should bring them down’