Masih Alinejad, an Iranian-American journalist and human-rights activist, likes to tell a story about walking through New York after appearing on various cable-TV networks to crusade against Iran’s oppression of women. Ms Alinejad, who has a nimbus of spiralling curls that makes her easy to recognise, describes being stopped by people who wanted to voice their support. But on one block a person pleaded with her not to appear again on Fox News (“They are miserable”) while on the next a person urged her to stop going on CNN (“They are using you”).

“I was like, ‘Wow, wow—guys, having Fox News and CNN is the beauty of America,’” Ms Alinejad said, speaking at the Global Free Speech Summit at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, on October 18th, just days before prosecutors in Manhattan would charge four men, including a senior official in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps of Iran, with plotting to kill her in 2022. Americans who wanted to cancel either network and watch only one, Ms Alinejad continued, might consider life in North Korea or Iran, where “You only see people repeating the narrative of the government, and you only see your family members and your heroes doing false confession in order to survive.”

That is a low bar. However, it is a fair point, and a chastening one as the climax approaches of an election campaign that has members of both parties despairing about their democracy. American news organisations may not always make the best use of their freedom, yet their very freedom to misuse their freedom is a measure of what keeps America great. In Ms Alinejad’s spirit, it seems worth considering other ways in which this much maligned campaign is revealing the vitality of America’s democracy—along with the pernicious effects of negative partisanship explored in our Essay this week.

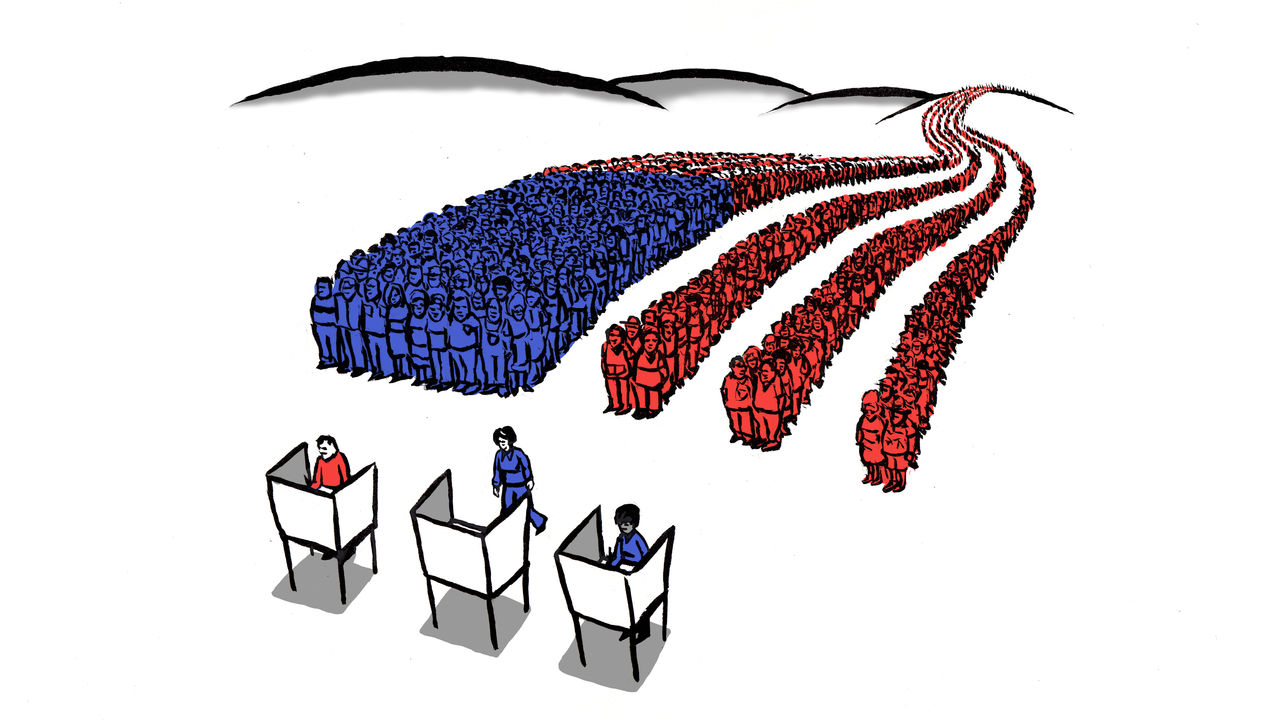

Start with what can be a basic vital sign: participation. A generation ago, when about half of eligible voters might turn up at the polls, America’s mandarins were sounding warnings about voter apathy and assembling commissions to overcome it. But two-thirds of eligible voters cast ballots in 2020, the highest proportion since 1900, and voting in the midterms of 2018 and 2022 reached levels not seen in decades. This autumn some states with early voting are setting records for participation. (A related sign of vitality is that, contrary to worries that threats and scorn directed at election officials would scare off poll workers, state offices are reporting ample levels of volunteers and paid staff.)

Along with surging registration of new voters, higher turnout is changing the composition of the electorate in unpredictable ways. This shift appears to be settling dumb debates within both parties in recent years over whether turning out partisans matters far more than persuading independent-minded voters to support your candidate. In a changing yet evenly divided electorate, both turnout and persuasion are essential, and the campaigns have been putting this rather obvious insight into practice. More competition for more voters can only benefit the country.

Indeed, one cause or effect, or both, of these efforts at persuasion is that America is becoming less polarised by race. Both parties have discarded facile assumptions that black or Latino voters are monolithic on matters such as illegal immigration or policing. The left’s conviction that Donald Trump was succeeding solely by catering to white people began to fray after the 2020 election, when he made gains among Latino, Asian and black voters. He is courting them more vigorously in this campaign. That outreach has clashed at times with his core emphasis, reaching disaffected young men, as when a comedian popular with that group managed the rare feat of upstaging Mr Trump by telling racist jokes before he spoke at Madison Square Garden on October 27th.

Kamala Harris has been trying to reverse Democratic erosion among young non-white Americans while also trying to reach beyond her party’s base of voters with college degrees. Rather than repeating Joe Biden’s promises to erase college-loan debt, she is emphasising that she will create jobs that do not require a college education. “We understand a college degree is not the only measure of whether a worker has skills and experience to get the job done,” she declared at a rally in Flint, Michigan, in early October.

Ms Harris has also been bidding to win back rural voters Democrats have all but ignored in recent campaigns, while Mr Trump has been campaigning in big cities—and both of them appear to be having some success. Ms Harris has campaigned in solidly red Texas while Mr Trump has campaigned in such Democratic strongholds as California and New York. Both have campaigned with members of the opposing party, though Mr Trump’s few Democrats, such as Robert Kennedy junior, are party misfits of longer standing than Ms Harris’s Republicans, some of whom once worked for Mr Trump.

Use it or lose it

The imperative to attract less partisan voters has also compelled both candidates to moderate some of their more extreme views. Ms Harris has backed off leftist positions she espoused in 2019. Mr Trump, who has moved his party towards the centre on matters such as entitlements and gay rights, has been clumsily trying to moderate his stance on reproductive freedoms after a backlash he clearly did not expect to the Supreme Court’s decision in 2022 to eliminate the constitutional right to abortion.

Far more than other protest movements this century, the grassroots movement to restore abortion rights is proving durable and effective. It has won in all six states that have had plebiscites on abortion rights so far, including such conservative ones as Kansas and Kentucky. Americans, it seems, have not forgotten how to put their democracy to use in defence of their liberty. ■

Subscribers to The Economist can sign up to our new Opinion newsletter, which brings together the best of our leaders, columns, guest essays and reader correspondence.

Blog Post7 days ago

Blog Post7 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago