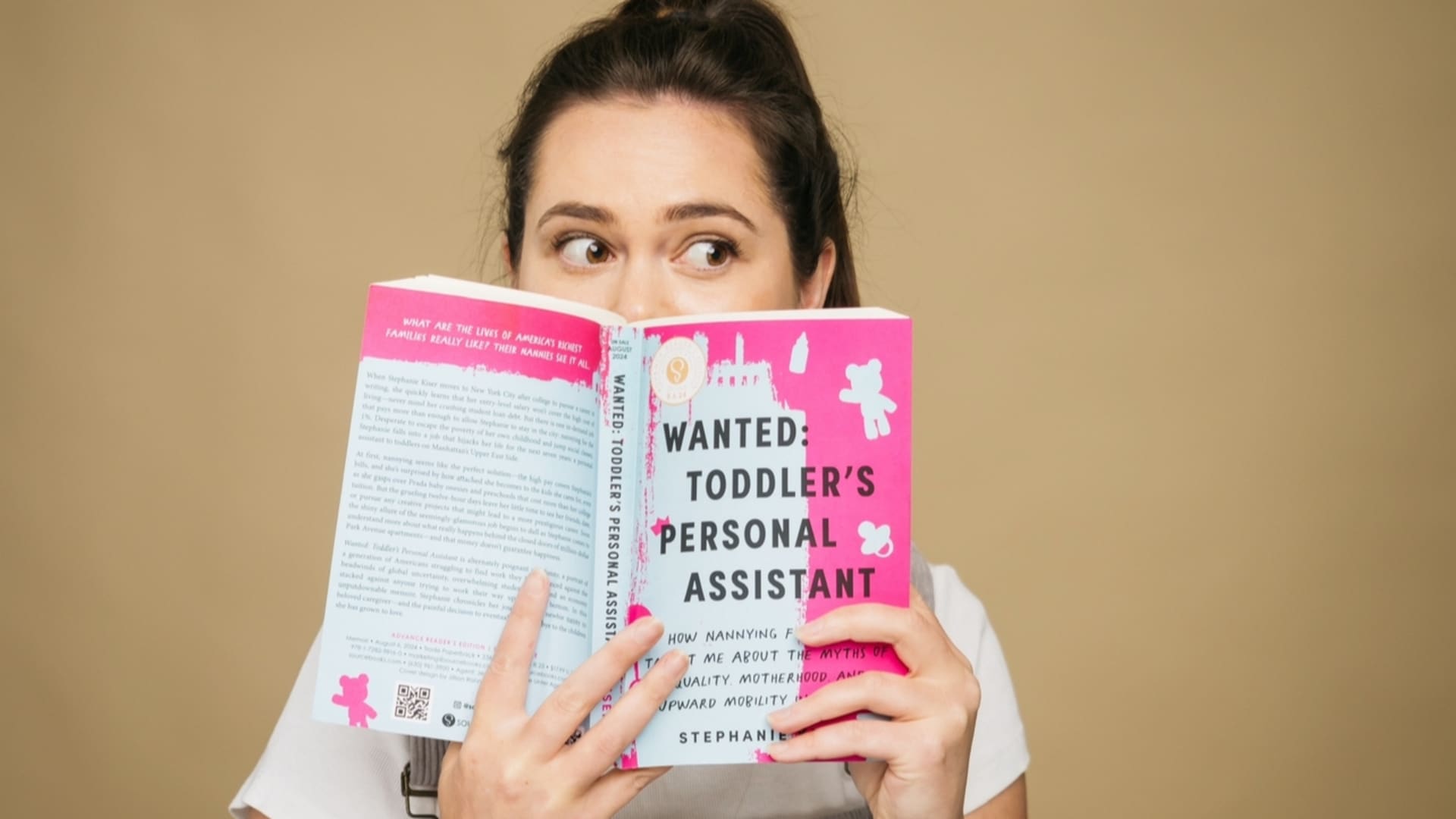

Stefanie Kiser Book: “Wanted: Toddler’s Personal Assistant”. Cover design by Jillian Rahn/Sourcebooks.

Courtesy: Stefanie Kiser

Stephanie Kiser came to New York City in 2014 as a new college graduate, hoping to become a screenwriter. Instead, she spent the next seven years as a nanny for wealthy families.

Kiser’s new memoir, “Wanted: Toddler’s Personal Assistant: How Nannying for the 1% Taught Me about the Myths of Equality, Motherhood, and Upward Mobility in America,” details her unexpected career detour.

Her seven years as a nanny saw her escorting one client’s daughter to $500-per-lesson literacy tutors on the Upper East Side, driving Porsches and Mercedes for everyday errands and sheltering in place at a family’s home in the Hamptons during the Covid-19 pandemic. Her clients included families with dynastic wealth as well as those with high-paying jobs such as doctors and lawyers.

More from Personal Finance:

This labor data trend is a ‘warning sign,’ economist says. Here’s why

Working remotely from a cruise ship? Here’s why the IRS still expects taxes

Here’s how Tim Walz could help shape the child tax credit

In Kiser’s first nannying job, she was paid $20 an hour, far more than the $14 an hour she estimates she would have made as a production assistant under a short-term contract. Plus, she often ended up working extra hours.

“It usually ended up being like $1,000 a week with everything that I was doing,” Kiser said.

That first job opened doors for higher-paid positions through nanny agencies. In Kiser’s final year as a nanny during the pandemic, she estimates she took home about $110,000.

“Even though I had the least respected job of my friends, I definitely was making the most,” said Kiser, who is now 32 and works at an ad-tech company in New York City.

CNBC spoke with Kiser about some of the financial lessons she learned during her time as a nanny, and why she ultimately left the role.

(This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity).

No prospects for job growth: ‘I was very stationary’

Scarlett Johansson on Location for “The Nanny Diaries” on May 1, 2006 at Upper East Side in New York City, New York, United States.

James Devaney | Wireimage | Getty Images

Ana Teresa Solá: When I first saw this book, I thought of “The Nanny Diaries,” a novel published in the early 2000s and then adapted into a movie. What made you decide to turn your story into a memoir instead of a novel?

Stephanie Kiser: I read “The Nanny Diaries” when I started my first job. It definitely hit home at the time, but I did feel like it was sort of a satire. I didn’t want to villainize the rich or the poor because I have people I love very dearly on both sides.

The intention of my book was to make a social commentary. It was my hope that I could bridge this understanding a bit between the two sides because there’s this thought that poor people just aren’t working hard enough and rich people are just inherently bad.

I don’t think that’s necessarily true, but I think that people who are wealthy, who are employing these people who really need these jobs, they do have privilege and an opportunity to either make someone’s life better or worse.

A contract as a nanny is important because there’s no HR.

ATS: You mention that you could not afford to work in a professional job in New York because the pay was much lower than you were making as a nanny. Did you feel trapped?

SK: When my last boss read this book, she felt sad and was like, ‘I didn’t realize you were so miserable doing the job.’ I said, ‘No, I wasn’t miserable doing the job. I loved your kids so much, but this was not the job I wanted.’

I did feel trapped. I felt like there’s nothing else I could possibly do, and it got a little bit worse as time went on.

All my friends were growing in these jobs and they were getting more experience in their resume, and I wasn’t. I was very stationary in this position.

It wasn’t a good feeling to feel like there’s nothing else I could possibly do. Now I have a different job and this is the first year that I’m earning more than I did nannying, which is great, but the first couple of years after nannying were definitely really hard financially, making that shift.

‘There’s no HR … the contract is really all you have’

ATS: A family offered you a salary of $125,000, plus full health and dental, a monthly metro card and an annual bonus. But you went with a different family for less pay. You mentioned you were waiting on a contract. Why is that so important in the business?

SK: A contract as a nanny is important because there’s no human resources; there’s no laws protecting you. Your employers are fully in charge of everything and they determine everything. [New York State does have a “Domestic Workers Bill of Rights” with a few protections.]

At a regular job, you can be like, ‘I worked 60 hours already this week, and I’m not going to work more.’ You can’t do that here [with a nanny position.]

The contract is really all you have, and to not get the contract was really worrisome. Your whole life was going to be a nanny for this family. And I was coming off of a job where that had been really tricky, feeling like I wasn’t really a person, and I didn’t want to accept a job where that was the case again.

Stefanie Kiser Book: “Wanted: Toddler’s Personal Assistant”. Cover design by Jillian Rahn/Sourcebooks.

Courtesy: Stefanie Kiser

ATS: Can you describe the differences between an au pair and a nanny?

SK: An au pair is allowed to work a certain number of hours, like up to 30 hours a week or 40 hours a week, but there is a clear boundary because they often work for an agency. The agency that has sent them has told you very clearly they cannot work more than this.

They get a very small stipend, but they do get specific accommodations, maybe they have their own room. They have all their meals paid for, transportation. An au pair has more things in place to make sure that they’re not taken advantage of. Nannies often don’t have these protections.

Nannies who come from agencies are slightly more protected and those are typically the ones who get contracts. But these are the best of the best nannies; these are career nannies who have been doing this for 50 years; they’ve raised so many kids and they have amazing references. Or it’s a young nanny that just got here after graduating from a great university and has like 10 skills that they are able to offer. So this is a luxury, honestly.

ATS: You also describe the uncertainty associated with this job. It seems like nannying work can have a low barrier to entry, with salary growth potential, but then there are all these other risks.

SK: I’ve known nannies who’ve gotten pregnant and they tell their boss. There’s no, ‘We’re going to pay you three months maternity.’ there’s no, ‘We’re gonna let you leave on month eight so you can rest.’ There’s none of that.

You can never really feel safe in the job. If you have a medical emergency, if anything goes wrong — I’m sure there’s exceptions, but for the most part, you’re sort of just out of luck. It is a really risky career in that sense.

‘That’s how you know they’re wealthy’

ATS: According to the Pew Research Center, about 47% of childless adults under 50 in 2023 said they are unlikely to ever have children. What would that mean for nannies?

SK: I wonder if that applies to the sort of people that I’m writing about. I wonder if for them this is a decline we’ll see or if they’re sort of outliers.

If it is the case, I think it’s a really serious problem. There are a lot of people in New York who come here and they need something to get by, who babysit, maybe it’s their after work job and that’s how they do it. Or there’s people who don’t have papers that are really limited in what they can do, and a lot of times, housekeeping and nannying is the only option.

ATS: At the end of the book, you write that you received an offer as a personal assistant for a CEO with a $90,000 salary and benefits. Was that starting point below what you had been earning as a nanny at the time?

SK: For sure. As a nanny, I had made $110,000 … So it was a significant decrease.

I had to work very quickly and very hard to get promoted. I was a personal assistant and I was an executive assistant, I changed companies last July and I became a senior assistant, and that was the role where I finally made more than I did nannying. And I don’t think I could have done this, made this transition, if my student loan payments weren’t paused because of Covid.

ATS: You write in your book that some families signal their wealth by having many children. I’m curious to hear more about that.

SK: I think about where I was born and where I came from, and anytime there was a family that had like five or six kids, it was sort of like, ‘Well that makes sense, because they weren’t wealthy.’ And then you come to New York and you see someone on Park Avenue that has five or six kids, and it’s like, ‘That’s how you know they’re wealthy.’

Here, if you do have three kids, you start sending them to preschool at $40,000 a year, and then they’re going to these elite schools from kindergarten to 12th grade that are $60,000 a year, and then you’re sending them to Harvard for four years.

And it’s not even just the schooling, it’s most of the time you’re sending three kids to this school, then you’re employing a full-time nanny after they have private guitar lessons.

ATS: What would you tell women in their 20s who are in the shoes you were in a few years ago?

SK: Do things in parallel. I don’t think I would have been happy if I had done just the nannying. I couldn’t have survived on just writing, but I think that by doing this in parallel, things turned out exactly how they were supposed to be for me.

Nannying was so important for me because not only was I able to make money to live, but it allowed me to get a foundation. When I moved to New York, I had nothing. Now I have a fully furnished apartment, things that you need to be a fully functioning adult. I have a dog, I’m able to take care of him and I have a car. These are things that I couldn’t have done without being a nanny.

Blog Post7 days ago

Blog Post7 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago