Economics

Why the Fed keeping rates higher for longer may not be such a bad thing

Published

3 weeks agoon

US Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome Powell arrives to testify at a House Financial Services Committee hearing on the “Federal Reserve’s Semi-Annual Monetary Policy Report,” on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, March 6, 2024.

Mandel Ngan | Afp | Getty Images

With the economy humming along and the stock market, despite some recent twists and turns, hanging in there pretty well, it’s a tough case to sell that higher interest rates are having a substantially negative impact on the economy.

So what if policymakers just decide to keep rates where they are for even longer, and go through all of 2024 without cutting?

It’s a question that, despite the current conditions, makes Wall Street shudder and Main Street queasy as well.

“When rates start climbing higher, there has to be an adjustment,” said Quincy Krosby, chief global strategist at LPL Financial. “The calculus has changed. So the question is, are we going to have issues if rates remain higher for longer?”

The higher-for-longer stance was not what investors were expecting at the beginning of 2024, but it’s what they have to deal with now as inflation has proven stickier than expected, hovering around 3% compared with the Federal Reserve’s 2% target.

Recent statements by Fed Chair Jerome Powell and other policymakers have cemented the notion that rate cuts aren’t coming in the next several months. In fact, there even has been talk about the potential for an additional hike or two ahead if inflation doesn’t ease further.

That leaves big questions over when exactly monetary policy easing will come, and what the central bank’s position to remain on hold will do to both financial markets and the broader economy.

Krosby said some of those answers will come soon as the current earnings season heats up. Corporate officers will provide key details beyond sales and profits, including the impact that interest rates are having on profit margins and consumer behavior.

“If there’s any sense that companies have to start cutting back costs and that leads to labor market trouble, this is the path of a potential problem with rates this high,” Krosby said.

But financial markets, despite a recent 5.5% sell-off for the S&P 500, have largely held up amid the higher-rate landscape. The broad market, large-cap index is still up 6.3% year to date in the face of a Fed on hold, and 23% above the late October 2023 low.

Higher rates can be a good sign

History tells differing stories about the consequences of a hawkish Fed, both for markets and the economy.

Higher rates are generally a good thing so long as they’re associated with growth. The last period when that wasn’t true was when then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker strangled inflation with aggressive hikes that ultimately and purposely tipped the economy into recession.

There is little precedent for the Fed to cut rates in robust growth periods such as the present, with gross domestic product expected to accelerate at a 2.4% annualized pace in the first quarter of 2024, which would mark the seventh consecutive quarter of growth better than 2%. Preliminary first-quarter GDP numbers are due to be reported Thursday.

In the 20th century, at least, it’s tough to make the argument that high rates led to recessions.

On the contrary, Fed chairs have often been faulted for keeping rates too low for too long, leading to the dot-com bubble and subprime market implosions that triggered two of the three recessions this century. In the other one, the Fed’s benchmark funds rate was at just 1% when the Covid-induced downturn occurred.

In fact, there are arguments that too much is made of Fed policy and its broader impact on the $27.4 trillion U.S. economy.

“I don’t think that active monetary policy really moves the economy nearly as much as the Federal Reserve thinks it does,” said David Kelly, chief global strategist at J.P. Morgan Asset Management.

Kelly points out that the Fed, in the 11-year run between the financial crisis and the Covid pandemic, tried to bring inflation up to 2% using monetary policy and mostly failed. Over the past year, the pullback in the inflation rate has coincided with tighter monetary policy, but Kelly doubts the Fed had much to do with it.

Other economists have made a similar case, namely that the main issue that monetary policy influences — demand — has remained robust, while the supply issue that largely operates outside the reach of interest rates has been the principle driver behind decelerating inflation.

Where rates do matter, Kelly said, is in financial markets, which in turn can affect economic conditions.

“Rates too high or too low distort financial markets. That ultimately undermines the productive capacity of the economy in the long run and can lead to bubbles, which destabilizes the economy,” he said.

“It’s not that I think they’ve set rates at the wrong level for the economy,” he added. “I do think the rates are too high for financial markets, and they ought to try to get back to normal levels — not low levels, normal levels — and keep them there.”

Higher-for-longer the likely path

As a matter of policy, Kelly said that would translate into three quarter-percentage point rate cuts this year and next, taking the fed funds rate down to a range of 3.75%-4%. That’s about in line with the 3.9% rate at the end of 2025 that Federal Open Market Committee members penciled in last month as part of their “dot-plot” projections.

Futures market pricing implies a fed funds rate of 4.32% by December 2025, indicating a higher rate trajectory.

While Kelly is advocating for “a gradual normalization of policy,” he does think the economy and markets can withstand a permanently higher level of rates.

In fact, he expects the Fed’s current projection of a “neutral” rate at 2.6% is unrealistic, an idea that is gaining traction on Wall Street. Goldman Sachs, for instance, recently has opined that the neutral rate — neither stimulative nor restrictive — could be as high as 3.5%. Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester also recently said it’s possible that the long-run neutral rate is higher.

That leaves expectations for Fed policy tilting toward cutting rates somewhat but not going back to the near-zero rates that prevailed in the years after the financial crisis.

In fact, over the long run, the fed funds rate going back to 1954 has averaged 4.6%, even given the extended seven-year run of near-zero rates after the 2008 crisis until 2015.

Government spending issues

One thing that has changed dramatically, though, over the decades has been the state of public finances.

The $34.6 trillion national debt has exploded since Covid hit in March 2020, rising by nearly 50%. The federal government is on track to run a $2 trillion budget deficit in fiscal 2024, with net interest payments thanks to those higher interest rates on pace to surpass $800 billion.

The deficit as a share of GDP in 2023 was 6.2%; by comparison, the European Union allows its members only 3%.

The fiscal largesse has juiced the economy enough to make the Fed’s higher rates less noticeable, a condition that could change in the days ahead if benchmark rates hold high, said Troy Ludtka, senior U.S. economist at SMBC Nikko Securities America.

“One of the reasons why we haven’t noticed this monetary tightening is simply a reflection of the fact that the U.S. government is running its most irresponsible fiscal policy in a generation,” Ludtka said. “We’re running massive deficits into a full-employment economy, and that’s really keeping things afloat.”

However, the higher rates have begun to take their toll on consumers, even if sales remain solid.

Credit card delinquency rates climbed to 3.1% at the end of 2023, the highest level in 12 years, according to Fed data. Ludtka said the higher rates are likely to result in a “retrenchment” for consumers and ultimately a “cliff effect” where the Fed ultimately will have to concede and lower rates.

“So, I don’t think they should be cutting anytime in the immediate future. But at some point that’s going to have to happen, because these interest rates are simply crushing particularly low-income-earning Americans,” he said. “That is a big portion of the population.”

Don’t miss these exclusives from CNBC PRO

You may like

-

U.S. job growth totaled 175,000 in April

-

Immigrant workers are helping boost the U.S. labor market

-

Jobless rates rise in April for all race groups except Black Americans

-

Turkey’s inflation accelerates to nearly 70% in April

-

UK to suffer slowest growth of all rich nations next year, OECD says

-

Wall Street is confused and divided over how many times the Fed will cut rates this year

This is the introduction to Checks and Balance, a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter bringing exclusive insight from our correspondents in America.

Sign up for Checks and Balance.

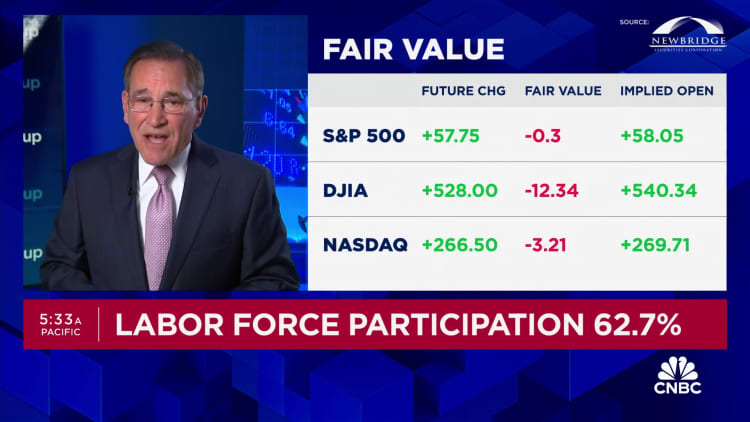

The U.S. economy added fewer jobs than expected in April while the unemployment rate rose, lifting hopes that the Federal Reserve will be able to cut interest rates in the coming months.

Nonfarm payrolls increased by 175,000 on the month, below the 240,000 estimate from the Dow Jones consensus, the Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics reported Friday. The unemployment rate ticked higher to 3.9% against expectations it would hold steady at 3.8%.

Average hourly earnings rose 0.2% from the previous month and 3.9% from a year ago, both below consensus estimates and an encouraging sign for inflation.

The jobless rate tied for the highest level since January 2022. A more encompassing rate that includes discouraged workers and those holding part-time jobs for economic reasons also edged up, to 7.4%, its highest level since November 2021. The labor force participation rate, or those actively looking for work, was unchanged at 62.7%.

Wall Street already had been poised for a higher open, and futures tied to major stock market averages added to gains following the report. Treasury yields tumbled after being little changed before the release. The report raised the prospect of a “Goldilocks” climate where growth continues but not at such a rapid pace to force the Fed to tighten policy further.

“With this report, the porridge was just about right,” said Dan North, senior economist at Allianz Trade. “What would you like at this point the cycle? We’ve had interest rates jacked up pretty high, so you would expect to see the labor market slow down a little. But we’re still at pretty high levels.”

Consistent with recent trends, health care led job creation, with a 56,000 increase.

Other sectors showing significant rises included social assistance (31,000), transportation and warehousing (22,000), and retail (20,000). Construction added 9,000 positions while government, which had shown solid gains in recent months, was up just 8,000 after averaging 55,000 over the previous 12 months.

Revisions to previous months took the March gain to 315,000, or 12,000 from the initial estimate, and February to 236,000, a decline of 34,000.

Household employment, which is used to calculate the unemployment rate, increased by just 25,000 on the month. Workers holding full-time jobs soared by 949,000 on the month, while those hold part-time jobs slumped by 914,000.

The report comes two days after the Fed again voted to hold borrowing costs steady, keeping its benchmark overnight borrowing rate in a targeted range between 5.25%-5.5%, the highest in more than 20 years.

Following the decision, Chair Jerome Powell characterized the jobs market as “strong” but noted that inflation is “too high” and this year’s economic data has indicated “a lack of further progress” in getting inflation back to the Fed’s 2% target.

But market action shifted after the jobs report indicated an easing labor market and softer wage increases. Traders priced in a strong chance of two interest rate cuts by the end of 2024, with the first reduction expected to come in September, according to CME Group data.

“This is the jobs report the Fed would have scripted,” said Seema Shah, chief global strategist at Principal Asset Management. “The first downside payrolls surprise in several months, as well as the dip in average hourly earnings growth, will bring the rate cutting dialogue back into the market and perhaps explains why Powell was able to be dovish on Wednesday.”

Though inflation has come well off its highs in mid-2022, it is still considerably above the central bank’s comfort zone. Most reports this year have shown inflation around 3% annually; the Fed’s own preferred measure, the core personal consumption expenditures price index, most recently was at 2.8%.

Higher prices have been putting upward pressure on wages, part of an inflation picture that has kept the Fed on the sidelines despite widespread market expectations that the central bank would be cutting interest rates aggressively this year.

Most Fed officials in fact had been mentioning the likelihood of reductions in their public comments. However, Powell at his post-meeting news conference Wednesday made no mention of the likelihood that rates would be lowered at some point this year, as he had in the past.

Don’t miss these exclusives from CNBC PRO

Economics

Immigrant workers are helping boost the U.S. labor market

Published

2 weeks agoon

May 4, 2024

The strong jobs market has been bolstered post-pandemic by strength in the immigrant workforce in America. And as Americans age out of the labor force and birth rates remain low, economists and the Federal Reserve are touting the importance of immigrant workers for overall future economic growth.

Immigrant workers made up 18.6% of the workforce last year, a new record, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Workers are taking open positions in agriculture, technology and health care, fields where labor supply has been a challenge for those looking to hire.

Despite the U.S. adding fewer-than-expected jobs in April, the labor force participation rate for foreign-born workers ticked up slightly, to 66%.

“We don’t have enough workers participating in the labor force and our birth rate has dropped down 2% last year from 2022 to 2023. … These folks are not taking jobs. They are helping to bolster and helping us build back — they’re adding needed workers to the labor force,” said Jennie Murray, CEO of the National Immigration Forum, a nonpartisan nonprofit advocacy organization.

The influx of immigrant workers is also a projected boost to U.S. output, and is expected to grow gross domestic product over the next decade by $7 trillion, Congressional Budget Office Director Phillip Swagel noted in a February statement accompanying the 2024-2034 CBO outlook.

“The labor force in 2033 is larger by 5.2 million people, mostly because of higher net immigration. As a result of those changes in the labor force, we estimate that, from 2023 to 2034, GDP will be greater by about $7 trillion and revenues will be greater by about $1 trillion than they would have been otherwise. We are continuing to assess the implications of immigration for revenues and spending,” Swagel wrote.

‘Huge competition’

Goodwin Living, a nonprofit faith-based elder-care facility in Northern Virginia that cares for 2,500 adults day to day, is heavily reliant on immigrant workers. Some 40% of its 1,200 workers are foreign-born, representing 65 countries, according to CEO Rob Liebreich, and more workers will be needed to fill increasing gaps as Americans age and need assistance.

“About 70% of 65-year-olds are expected to need long-term care in the future. We need a lot of hands to support those needs,” Liebreich told CNBC. “Right now, one of the best ways that we see to find that is through people coming from other countries, our global talent, and there’s a huge competition for them.”

In 2018, Goodwin launched a citizenship program, which provides financial resources, mentorship and tutoring for workers looking to obtain U.S. citizenship. So far, 160 workers and 25 of their family members have either obtained citizenship or are in the process of doing so through Goodwin.

Wilner Vialer, 35, began working at Goodwin four years ago and serves as an environmental services team lead, setting up and cleaning rooms. Vialer, who came to the U.S. 13 years ago from Haiti, lost his job during the pandemic and was given an opportunity at Goodwin because his mother had been employed at the facility.

He applied for U.S. citizenship before getting his current job, but after he worked there for six months, the Goodwin Living Foundation covered his application fee of $725, the nonprofit said. Vialer became a U.S. citizen in 2021, and his 15-year-old daughter received a citizenship grant and became a U.S. citizen in 2023.

Vialer’s hope is to have his wife join the family from Haiti, as they have been separated for six years.

“This program is a good opportunity,” Vialer said. “They help me, I have a family back home. … This job really [does] support me when I get my paycheck to help them back home.”

Workers are not required to stay with Goodwin after becoming U.S. citizens, but those who do stay are there 20% longer than those who do not participate in the program, Liebreich said. Speeding up the path to citizenship is key to remaining competitive in a global economy, he added.

“If we want to attract and retain this global workforce, which we desperately need, we need to make the process a lot easier,” Liebreich said.

Looking ahead to November, immigration will be a hot topic on the presidential campaign trail and for voters. Both President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump have made trips to the southern border in recent months to address the large number of migrants entering the country.

Betting on the Kentucky Derby? Here’s how to think like a professional handicapper.

Warren Buffett says Greg Abel will make Berkshire Hathaway investing decisions when he’s gone

EV makers win 2-year extension to qualify for tax credits

Are American progressives making themselves sad?

‘Best Firms for Tech’ 2024 deadline extended to April 10