Fatcamera | E+ | Getty Images

The House tax and spending bill would push millions of Americans off health insurance rolls, as Republicans cut programs like Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act to fund priorities from President Donald Trump, including almost $4 trillion of tax cuts.

The Congressional Budget Office, a nonpartisan legislative scorekeeper, projects about 11 million people would lose health coverage due to provisions in the House bill, if enacted in its current form. It estimates another 4 million or so would lose insurance due to expiring Obamacare subsidies, which the bill doesn’t extend.

The ranks of the uninsured would swell as a result of policies that would add barriers to access, raise insurance costs and deny benefits outright for some people like certain legal immigrants.

The legislation, known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” may change as Senate Republicans now consider it. Health care cuts have proven to be a thorny issue. A handful of GOP senators — enough to torpedo the bill — don’t appear to back cuts to Medicaid, for example.

More from Personal Finance:

How debt impact of House GOP tax bill may affect consumers

3 key money moves to consider while the Fed keeps interest rates higher

How child tax credit could change as Senate debates Trump’s mega-bill

The bill would add $2.4 trillion to the national debt over a decade, CBO estimates. That’s after cutting more than $900 billion from health care programs during that time, according to the Penn Wharton Budget Model.

The cuts are a sharp shift following incremental increases in the availability of health insurance and coverage over the past 50 years, including through Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act, according to Alice Burns, associate director with KFF’s program on Medicaid and the uninsured.

“This would be the biggest retraction in health insurance that we’ve ever experienced,” Burns said. “That’s makes it really difficult to know how people, providers, states, would react.”

Here are the major ways the bill would increase the number of uninsured.

No population ‘safe’ from proposed Medicaid cuts

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., pictured at a press conference after the House narrowly passed a bill forwarding President Donald Trump’s agenda on May 22 in Washington, DC.

Kevin Dietsch | Getty Images

Federal funding cuts to Medicaid will have broad implications, experts say.

“No population, frankly, is safe from a bill that cuts more than $800 billion over 10 years from Medicaid, because states will have to adjust,” said Allison Orris, senior fellow and director of Medicaid policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The provision in the House proposal that would lead most people to lose Medicaid and therefore become uninsured would be new work requirements that would apply to states that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, according to Orris.

The work requirements would affect eligibility for individuals ages 19 to 64 who do not have a qualifying exemption. Affected individuals would need to demonstrate they worked or participated in qualifying activities for at least 80 hours per month.

States would also need to verify that applicants meet requirements for one or more consecutive months prior to coverage, while also conducting redeterminations at least twice per year to ensure individuals who are already covered still comply with the requirements.

In a Sunday interview with NBC News’ “Meet the Press,” House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., said “4.8 million people will not lose their Medicaid coverage unless they choose to do so,” while arguing the work requirements are not too “cumbersome.”

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated the work requirements would prompt 5.2 million adults to lose federal Medicaid coverage. While some of those may obtain coverage elsewhere, CBO estimates the change would increase the number of people without insurance by 4.8 million.

Those estimates may be understated because they do not include everyone who qualifies but fails to properly report their work hours or submit the appropriate paperwork if they qualify for an exemption, said KFF’s Burns.

Overall, 10.3 million would lose Medicaid, which would lead to 7.8 million people losing health insurance, Burns said.

Proposal creates state Medicaid funding challenges

Protect Our Care supporters display “Hands Off Medicaid” message in front of the White House ahead of President Trump’s address to Congress on March 4 in Washington, D.C.

Paul Morigi | Getty Images Entertainment | Getty Images

While states have used health care provider taxes to generate funding for Medicaid, the House proposal would put a stop to using those levies in the future, Orris noted.

Consequently, with less revenue and federal support, states will face the tough choice of having to cut coverage or cut other parts of their state budget in order to maintain their Medicaid program, Orris said.

For example, home and community-based services could face cuts to preserve funding for mandatory benefits like inpatient and outpatient hospital care, she said.

The House proposal would also delay until 2035 two Biden-era eligibility rules that were intended to make Medicaid enrollment and renewal easier for people, especially older adults and individuals with disabilities, Burns said.

States would also have their federal matching rate for Medicaid expenditures reduced if they offer coverage to undocumented immigrants, she said.

Affordable Care Act cuts ‘wonky’ but ‘consequential’

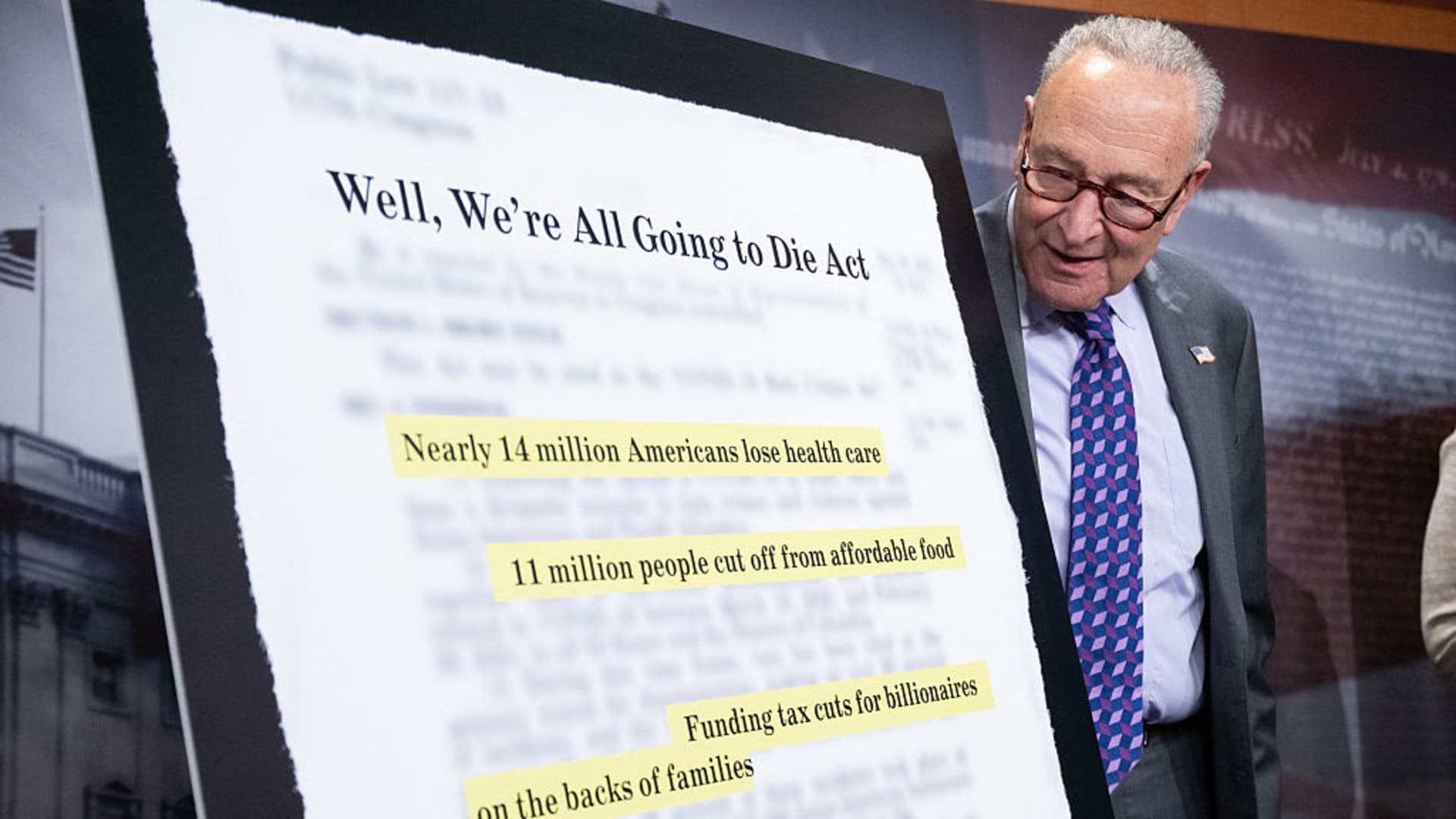

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., speaks about the health care impacts of the Republican budget and policy bill, also known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” during a June 4 news conference in Washington, D.C.

Saul Loeb | Afp | Getty Images

More than 24 million people have health insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplaces.

They’re a “critical” source of coverage for people who don’t have access to health insurance at their jobs, including for the self-employed, low-paid workers and older individuals who don’t yet qualify for Medicare, according to researchers at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-leaning think tank.

The House legislation would “dramatically” reduce ACA enrollment — and, therefore, the number of people with insurance — due to the combined effect of several changes rather than one big proposal, wrote Drew Altman, president and chief executive of KFF, a nonpartisan health policy group.

“Many of the changes are technical and wonky, even if they are consequential,” Altman wrote.

Expiring ACA subsidies add to coverage costs

ACA enrollment is at an all-time high. Enrollment has more than doubled since 2020, which experts largely attribute to enhanced insurance subsidies offered by Democrats in the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021 and then extended through 2025 by the Inflation Reduction Act.

Those subsidies, called “premium tax credits,” effectively reduce consumers’ monthly premiums. (The credits can be claimed at tax time, or households can opt to get them upfront via lower premiums.)

Congress also expanded the eligibility pool for subsidies to more middle-income households, and reduced the maximum annual contribution households make toward premium payments, experts said.

The enhanced subsidies lowered households’ premiums by $705 (or 44%) in 2024 — to $888 a year from $1,593, according to KFF.

The House Republican legislation doesn’t extend the enhanced subsidies, meaning they’d expire after this year.

About 4.2 million people will be uninsured in 2034 if the expanded premium tax credit expires, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

“They might just decide not to get [coverage] because they simply can’t afford to insure themselves,” said John Graves, a professor of health policy and medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Coverage will become more expensive for others who remain in a marketplace plan: The typical family of four with income of $65,000 will pay $2,400 more per year without the enhanced premium tax credit, CBPP estimates.

Adding red tape to eligibility, enrollment

More than 3 million people are expected to lose Affordable Care Act coverage as a result of other provisions in the House legislation, CBO projects.

Other “big” changes include broad adjustments to eligibility, said Kent Smetters, professor of business economics and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

For example, the bill shortens the annual open enrollment period by about a month, to Dec. 15, instead of Jan. 15 in most states.

It ends automatic re-enrollment into health insurance — used by more than half of people who renewed coverage in 2025 — by requiring all enrollees to take action to continue their coverage each year, CBPP said.

Senate Majority Leader Sen. John Thune (R-SD) (C) speak alongside Sen. John Barrasso (R-WY) (L) and Sen. Mike Crapo (R-ID) (R) outside the White House on June 4, 2025. The Senators met with President Donald Trump to discuss Trump’s “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” and the issues some members within the Republican Senate have with the legislation and its cost.

Anna Moneymaker | Getty Images News | Getty Images

The bill also bars households from receiving subsidies or cost-sharing reductions until after they verify eligibility details like income, immigration status, health coverage status and place of residence, according to KFF.

Graves says adding administrative red tape to health plans is akin to driving an apple cart down a bumpy road.

“The bumpier you make the road, the more apples will fall off the cart,” he said.

Uncapping subsidy repayments

Another biggie: The bill would eliminate repayment caps for premium subsidies.

Households get federal subsidies by estimating their annual income for the year, which dictates their total premium tax credit. They must repay any excess subsidies during tax season, if their annual income was larger than their initial estimate.

Current law caps repayment for many households; but the House bill would require all premium tax credit recipients to repay the full amount of any excess, no matter their income, according to KFF.

While such a requirement sounds reasonable, it’s unreasonable and perhaps even “cruel” in practice, said KFF’s Altman.

“Income for low-income people can be volatile, and many Marketplace consumers are in hourly wage jobs, run their own businesses, or stitch together multiple jobs, which makes it challenging, if not impossible, for them to perfectly predict their income for the coming year,” he wrote.

Curtailing use by immigrants

The House bill also limits marketplace insurance eligibility for some groups of legal immigrants, experts said.

Starting Jan. 1, 2027, many lawfully present immigrants such as refugees, asylees and people with Temporary Protected Status would be ineligible for subsidized insurance on ACA exchanges, according to KFF.

Additionally, the bill would bar Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipients in all states from buying insurance over ACA exchanges.

DACA recipients — a subset of the immigrant population known as “Dreamers” — are currently considered “lawfully present” for purposes of health coverage. That makes them eligible to enroll (and get subsidies and cost-sharing reductions) in 31 states plus the District of Columbia.

Blog Post6 days ago

Blog Post6 days ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago