A Federal Reserve interest rate cut won’t be coming until at least September, if at all this year, following a troubling inflation report Wednesday, according to updated market pricing.

Futures markets shifted from the expectation of a June cut and possibly another before the end of the year to no moves until the fall, with a minimal chance of a follow-up before the end of 2025.

“The Fed will see January’s hot inflation print as confirmation that price pressures continue to bubble beneath the economy’s surface,” Bill Adams, chief economist at Comerica, wrote in commentary that echoed others around Wall Street. “That will reinforce the Fed’s inclination to at least slow and possibly even end rate cuts in 2025.”

Reduced optimism for Fed easing came after the January consumer price index report showed a 0.5% monthly gain, pushing the annual inflation rate to 3%, a touch higher than December and only slightly lower than the 3.1% reading in January 2024. Excluding food and energy, the news was even worse, with a 3.3% rate that showed core inflation, which the Fed tends to rely on more even higher, also rising and holding well above the central bank’s goal.

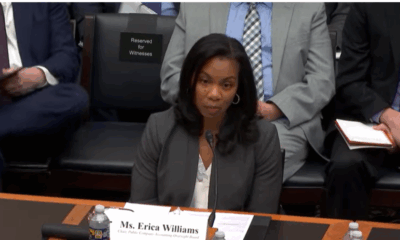

Fed Chair Jerome Powell, in an appearance Wednesday before the House Financial Services Committee, insisted the Fed had made “great progress” on inflation from its cycle peak “but we’re not quite there yet. So we want to keep policy restrictive for now.”

As the Fed targets 2% inflation and the report showed no recent progress, it also dimmed hopes that the central bank will view further policy easing as appropriate after it lopped a full percentage point off its benchmark short-term borrowing rate in 2024.

Fed funds futures trading pointed to just a 2.5% chance of a March cut; only 13.2% in May, up to 22.8% in June, then 41.2% in July and finally up to 55.9% in September, according to the CME Group’s FedWatch gauge as of late Wednesday morning. However, that would leave the probability still up in the air until October, when futures contracts pricing implies a 62.1% probability.

Odds of a second cut by the end of 2025 were at just 31.3%, with pricing not indicating another reduction until late 2026. The fed funds rate is currently targeted in a range between 4.25%-4.5%.

The issues raised in the CPI report are not happening in isolation. Policymakers also are watching White House trade policy, with President Donald Trump pushing aggressive tariffs that also could boost prices and complicate the Fed’s desire to get to its goal.

“There is no getting away from the fact that this is a hot report and with the sense that potential tariffs run upside risk for inflation the market is understandably of the view the Federal Reserve is going to find it challenging to justify rate cuts in the near future,” said James Knightley, chief international economist at ING.

While the Fed pays attention to CPI and other similar price measures, its preferred inflation gauge is the personal consumption expenditures index, which the Bureau of Economic Analysis will release later in February. Elements from CPI filter into the PCE reading, and Citigroup said it expects to see core PCE fall to 2.6% for January, a 0.2 percentage point decline from December.

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Finance7 days ago

Finance7 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago