ON THE FIRST day of his second term, President Donald Trump signed an executive order titled “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government.” The document marks a sweeping rollback of policies instituted during the Biden administration pertaining to sex, gender identity and transgender rights.

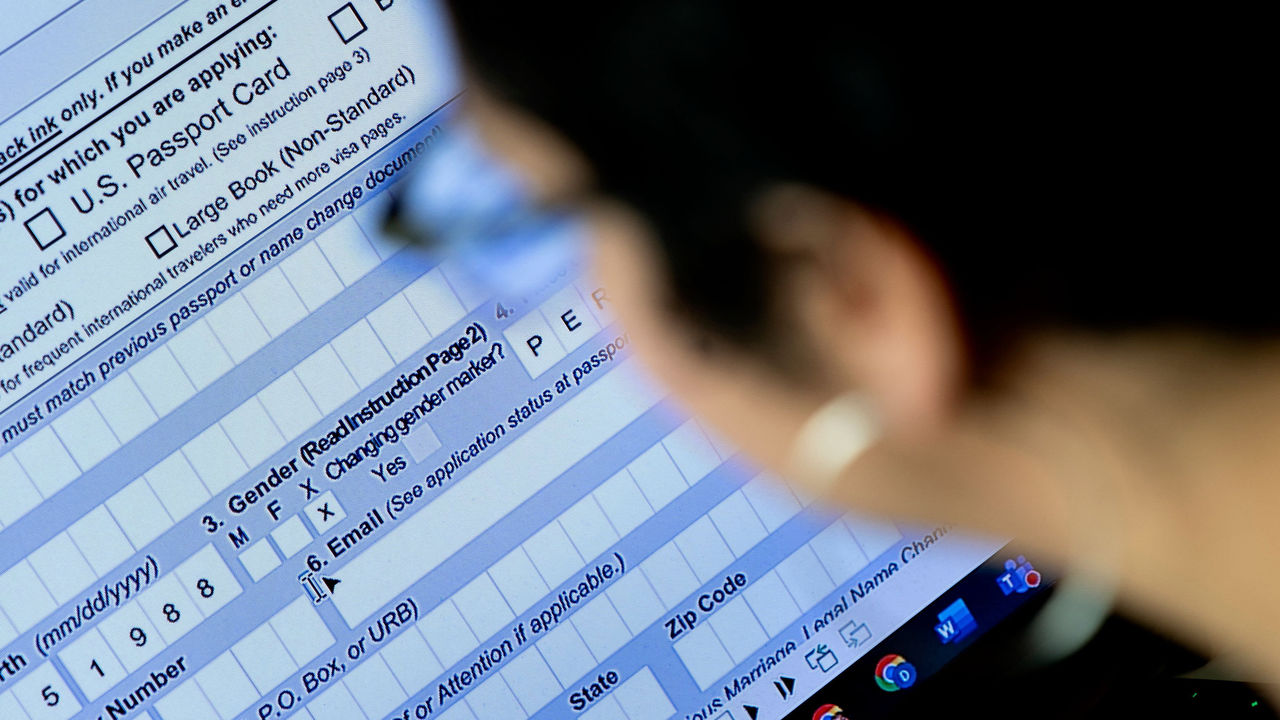

First, the order states that the federal government will henceforth use the traditional, biologically based definitions of terms like “male” and “female”. Then it calls for “gender ideology”, defined as the belief that someone’s subjective “gender identity” can trump their biological sex, to be in effect banished from the federal government: “Agencies shall remove all statements, policies, regulations, forms, communications, or other internal and external messages that promote or otherwise inculcate” this notion, “and shall take all necessary steps, as permitted by law, to end the Federal funding of gender ideology.”

Among other likely consequences of this edict, prisoners in federal custody who were born male are now to be housed in male prisons, regardless of their gender identities, and cut off from access to gender medicine by the order’s ban on federal funding. Transgender folks who have changed the markers on their passports to reflect their gender identities will probably have to change them back the next time they renew. On paper the order brooks few exceptions to its strict approach, describing as “false” the “claim that males can identify as and thus become women and vice versa”.

That being said, executive orders are not laws, and they can be blocked by the courts if they fall foul of existing legislation or the constitution. The most likely result is that some parts of “Defending Women” will be implemented and others held up or fully stymied by court challenges. A spokesperson at GLAD Law, an LGBT civil-rights organisation that plans on challenging the order, noted that every government action “must at a minimum have a valid non-discriminatory purpose and may be subject to a more exacting standard depending on the circumstances”, including “government actions based on animus toward a particular group”. So it is unclear how much power Mr Trump has to draw the boundaries of sex and gender.

However, on the single most important question animating all these issues—how the government defines “sex” in the first place—it is clear that nothing in Mr Trump’s executive order will permanently settle what has become a white-hot dispute.

Title VII of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act grants Americans protection from employment discrimination on the basis of a number of different categories, including “sex”. A later amendment, Title IX, outlaws such discrimination in federally funded educational settings. Nowhere in the law, however, is this term actually defined. According to Leor Sapir of the conservative Manhattan Institute, whose doctoral work focused on Title IX, the traditional understanding of sex has generally prevailed in federal civil-rights litigation, though there were cases under Title VII in which courts were open to the possibility that sex could mean or include a person’s self-conception.

That consensus began to crack in around 2010. “During the Obama Administration, the federal bureaucracy tried to rewrite the meaning of ‘sex’ in American civil-rights law through a convoluted administrative and judicial process, in co-operation with a number of federal judges,” Mr Sapir says. In May 2016 the administration published a so-called “Dear Colleague Letter” instructing public educational institutions to “treat a student’s gender identity as the student’s sex” when interpreting Title IX, meaning that if a student said they were a boy or a girl, they should be legally treated as one. This included allowing transgender students access to school facilities corresponding to their gender identity, with an exception for single-sex sports teams. This was one of the executive branch’s more important early attempts to change the definition of “sex” in a manner that would bring transgender people under pre-existing civil-rights protections.

It was short-lived, however. A federal court suspended enforcement of the letter on the grounds that it violated proper administrative procedure. About six few months later the newly inaugurated Trump administration revoked it anyway. Then in 2021 Joe Biden arrived ready to continue the process President Obama had started. In an executive order on his first day in office—now rescinded by Mr Trump and deleted from the White House’s website—Mr Biden laid out an agenda for protecting trans rights. His administration made a concerted effort, on multiple fronts, to embed a more expansive definition of “sex” in the federal government, but now Mr Trump appears poised to undo as much of it as possible. Even before Mr. Trump’s inauguration, just two weeks before Mr Biden and his team departed, a federal judge in Kentucky struck down their new rules extending Title IX protections to transgender students.

All of this, has led to what Doriane Coleman of Duke University School of Law described as a severe “whiplash” effect, with the government’s understanding of sex swinging wildly back and forth depending on the current administration’s policy preferences and, in some cases, the latest court rulings. While there is a strong possibility this whiplash will continue, there are two relatively straightforward—albeit unlikely—ways for the government to resolve it in a more durable manner.

First, Congress could simply pass a law finally codifying a specific definition of sex. In fact Mr Trump’s order instructs the White House’s legislative office to draft such a bill. That effort faces long odds, however: 60 senators would have to vote for the bill. Here, too, there’s a form of whiplash: in much the same way that Mr Trump’s order is something of a mirror-image of Mr Biden’s, the Democrats took their own shot at codifying their preferred understanding of sex via the Equality Act, which passed the House but could get no further. It would have explicitly defined sex as including gender identity, supplanting the traditional understanding of the term.

A Supreme Court decision could also partially dispel the government’s confusion over sex. According to Mr Sapir, there are about half a dozen cases concerning gender identity that SCOTUS can take up if it so chooses, concerning issues ranging from sports teams to free speech. While it is unlikely any of these cases will lead to a sweeping ruling settling the matter in its entirety, according to Mr Sapir, they could at least provide durable guidance as to how the government should understand sex in certain contexts. But unless and until such a resolution occurs, whether through Congress or the Supreme Court, the game of government fluidity on gender, already almost a decade old, is likely to continue. ■

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Accounting4 days ago

Accounting4 days ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Economics6 days ago

Economics6 days ago

Finance4 days ago

Finance4 days ago