Personal Finance

‘Climate gentrification’ fuels higher prices for longtime Miami residents

Published

10 months agoon

A development towers over the Lyric Theater in Miami’s Overtown neighborhood.

Greg Iacurci

MIAMI — Nicole Crooks stood in the plaza of the historic Lyric Theater, a royal blue hat shielding her from the midday sun that baked Miami.

In its heyday, the theater, in the city’s Overtown neighborhood, was an important cultural hub for the Black community. James Brown, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin and Ella Fitzgerald performed there, in the heart of “Little Broadway,” for esteemed audience members such as Jackie Robinson and Joe Louis.

Now, on that day in mid-March, the towering shell of a future high-rise development and a pair of yellow construction cranes loomed over the cultural landmark. It’s a visual reminder of the changing face of the neighborhood — and rising costs for longtime residents.

Located inland, far from prized beachfront real estate, Overtown was once shunned by developers and wealthy homeowners, said Crooks, a community engagement manager at Catalyst Miami, a nonprofit focused on equity and justice.

Nicole Crooks stands in the plaza of the Lyric Theater in Overtown, Miami.

Greg Iacurci

But as Miami has become ground zero for climate change, Overtown has also become a hot spot for developers fleeing rising seas and coastal flood risk, say climate experts and community advocates.

That’s because Overtown — like districts such as Allapattah, Liberty City, Little Haiti and parts of Coconut Grove — sits along the Miami Rock Ridge. This elevated limestone spine is nine feet above sea level, on average — about three feet higher than Miami’s overall average.

A development boom in these districts is changing the face of these historically Black neighborhoods and driving up prices, longtime residents tell CNBC. The dynamic is known as “climate gentrification.”

More from Personal Finance:

Why your finances aren’t insulated from climate change

People are moving to Miami and building there despite climate risk

Here’s how to buy renewable energy from your electric utility

Gentrification due to climate change is also happening in other parts of the U.S. and is one way in which climate risks disproportionately fall on people of color.

“More than anything, it’s about economics,” Crooks said of the encroachment of luxury developments in Overtown, where she has lived since 2011. “We’re recognizing that what was once prime real estate [on the coast] is not really prime real estate anymore” due to rising seas.

If Miami is ground zero for climate change, then climate gentrification makes Overtown and other historically Black neighborhoods in the city “ground zero of ground zero,” Crooks said.

Why the wealthy ‘have an upper hand’

When a neighborhood gentrifies, residents’ average incomes and education levels, as well as rents, rise rapidly, said Carl Gershenson, director of the Princeton University Eviction Lab.

Because of how those elements correlate, the outcome is generally that the white population increases and people of color are priced out, he said.

Gentrification is “inevitable” in a place such as Miami because so many people are moving there, including many wealthy people, Gershenson said.

But climate change “molds the way gentrification is going to happen,” he added.

Part of the building site of the Magic City development in Little Haiti.

Greg Iacurci

Indeed, climate gentrification has exacerbated a “pronounced housing affordability crisis” in Miami, particularly for immigrants and low-income residents, according to a recent analysis by real estate experts at Moody’s.

Asking rents have increased by 32.2% in the past four years to $2,224 per unit, on average — higher than the U.S. average of 19.3% growth and $1,825 per unit, according to Moody’s.

The typical renter in Miami spends about 43% of their income on rent, making the metro area the least affordable in the U.S., according to May data from Zillow.

Housing demand has soared due to Miami’s transition into a finance and technology hub, which has attracted businesses and young workers, pushing up prices, Moody’s said.

But rising seas and more frequent and intense flooding have made neighborhoods such as Little Haiti, Overtown and Liberty City — historically occupied by lower-income households — more attractive to wealthy people, Moody’s said.

The rich “have an upper hand” since they have the financial means to relocate away from intensifying climate hazards, it said.

“These areas, previously overlooked, are now valued for their higher elevation away from flood-prone zones, which leads to development pressure,” according to Moody’s.

These shifts in migration patterns “accelerate the displacement of established residents and inflate property values and taxes, widening the socio-economic divide,” it wrote.

Indeed, real estate at higher elevations of Miami-Dade County has appreciated at a faster rate since 2000 than that in other areas of the county, according to a 2018 paper by Harvard University researchers.

Many longtime residents rent and therefore don’t seem to be reaping the benefits of higher home values: Just 26% of homes occupied in Little Haiti are occupied by their owners, for example, according to a 2015 analysis by Florida International University.

In Little Haiti, the Magic City Innovation District, a 17-acre mixed-use development, is in the early stages of construction.

Robert Zangrillo, founder, chairman and CEO of Dragon Global, one of the Magic City investors, said the development will “empower” and “uplift” — rather than gentrify — the neighborhood.

He said the elevation was a factor in the location of Magic City, as were train and highway access, proximity to schools and views.

“We’re 17 to 20 feet above sea level, which eliminates flooding,” he said. “We’re the highest point in Miami.”

Effects of high costs ‘simply heartbreaking’

Comprehensive real estate data broken down according to neighborhood boundaries is hard to come by. Data at the ZIP-code level offers a rough approximation, though it may encompass multiple neighborhoods, according to analysts.

For example, residents of northwest Miami ZIP code 33127 have seen their average annual property tax bills jump 60% between 2019 and 2023, to $3,636, according to ATTOM, a company that tracks real estate data. The ZIP code encompasses parts of Allapattah, Liberty City and Little Haiti and borders Overtown.

That figure exceeds the 37.4% average growth for all of Miami-Dade County and 14.1% average for the U.S., according to ATTOM.

Higher property taxes often go hand in hand with higher property values, as developers build nicer properties and homes sell for higher prices. Wealthier homeowners may also demand more city services, pushing up prices.

A high-rise development in Overtown, Miami.

Greg Iacurci

Average rents in that same ZIP code have also exceeded those of the broader region, according to CoreLogic data.

Rents for one- and two-bedroom apartments jumped 50% and 52%, respectively, since the first quarter of 2021, according to CoreLogic.

By comparison, the broader Miami metro area saw one-bedroom rents grow by roughly 37% to 39%, and about 45% to 46% for two-bedroom units. CoreLogic breaks out data for two Miami metro divisions: Miami-Miami Beach-Kendall and West Palm Beach-Boca Raton-Delray Beach.

“To see how the elders are being pushed out, single mothers having to resort to living in their cars with their children in order to live within their means … is simply heartbreaking for me,” Crooks said.

‘Canaries in the coal mine’

Climate gentrification isn’t just a Miami phenomenon: It’s happening in “high-risk, high-amenity areas” across the U.S., said Princeton’s Gershenson.

Honolulu is another prominent example of development capital creeping inland to previously less desirable areas, said Andrew Rumbach, senior fellow at the Urban Institute. It’s a trend likely to expand to other parts of the nation as the fallout from climate change worsens.

Miami and Honolulu are the “canaries in the coal mine,” he said.

But climate gentrification can take many forms. For example, it also occurs when climate disasters reduce the supply of housing, fueling higher prices.

Smoke from the Marshall Fire in Louisville, Colorado.

Chris Rogers | Photodisc | Getty Images

In the year following the 2021 Marshall Fire in Colorado — the costliest fire in the state’s history — a quarter of renters in the communities affected by the fire saw their rents swell by more than 10%, according to survey data collected by Rumbach and other researchers. That was more than double the region-wide average of 4%, he said.

The supply that’s repaired and rebuilt generally costs more, too — favoring wealthier homeowners, the researchers found.

Across the U.S., high-climate-risk areas where disasters serially occur experience 12% higher rents, on average, according to recent research by the Georgia Institute of Technology and the Brookings Institution.

“It’s basic supply and demand: After disasters, housing costs tend to increase,” said Rumbach.

‘My whole neighborhood is changing’

Fredericka Brown, 92, has lived in Coconut Grove all her life.

Recent development has irreparably altered her neighborhood, both in character and beauty, she said.

“My whole neighborhood is changing,” said Brown, seated at a long table in the basement of the Macedonia Missionary Baptist Church. Founded in 1895, it’s the oldest African-American church in Coconut Grove Village West.

The West Grove district, as it’s often called, is where some Black settlers from the Bahamas put down roots in the 1870s.

“They’re not building single-family [houses] here anymore,” Brown said. The height of buildings is “going up,” she said.

Fredericka Brown (L) and Carolyn Donaldson (R) at the Macedonia Missionary Baptist Church in Coconut Grove.

Greg Iacurci

Carolyn Donaldson, sitting next to her, agreed. West Grove is located at the highest elevation in the broader Coconut Grove area, said Donaldson, a resident and vice chair of Grove Rights and Community Equity.

The area may well become “waterfront property” decades from now if rising seas swallow up surrounding lower-lying areas, Donaldson said. It’s part of a developer’s job to be “forward-thinking,” she said.

Development has contributed to financial woes for longtime residents, she added, pointing to rising property taxes as an example.

“All of a sudden, the house you paid for years ago and you were expecting to leave it to your family for generations, you now may or may not be able to afford it,” Donaldson said.

Why elevation matters for developers

Developers have been active in the City of Miami.

The number of newly constructed apartment units in multifamily buildings has grown by 155% over the past decade, versus 44% in the broader Miami metro area and 25% in the U.S., according to Moody’s data. Data for the City of Miami counts growth in overall apartment inventory in buildings with 40 or more units. The geographical area includes aforementioned gentrifying neighborhoods and others such as the downtown area.

While elevation isn’t generally “driving [developers’] investment thesis in Miami, it’s “definitely a consideration,” said David Arditi, a founding partner of Aria Development Group. Aria, a residential real estate developer, generally focuses on the downtown and Brickell neighborhoods of Miami and not the ones being discussed in this article.

Flood risk is generally why elevation matters: Lower-lying areas at higher flood risk can negatively affect a project’s finances via higher insurance rates, which are “already exorbitant,” Arditi said. Aria analyzes flood maps published by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and aims to build in areas that have lower relative risk, for example, he said.

“If you’re in a more favorable flood zone versus not … there’s a real sort of economic impact to it,” he said. “The insurance market has, you know, quadrupled or quintupled in the past few years, as regards the premium,” he added.

A 2022 study by University of Miami researchers found that insurance rates — more so than the physical threat of rising seas — are the primary driver of homebuyers’ decision to move to higher ground.

“Presently, climate gentrification in Miami is more reflective of a rational economic investment motivation in response to expensive flood insurance rather than sea-level rise itself,” the authors, Han Li and Richard J. Grant, wrote.

Some development is likely needed to address Miami’s housing crunch, but there has to be a balance, Donaldson said.

“We’re trying to hold on to as much [of the neighborhood’s history] as we possibly can and … leave at least a legacy and history here in the community,” she added.

Tearing down old homes and putting up new ones can benefit communities by making them more resilient to climate disasters, said Todd Crowl, director of the Florida International University Institute of Environment.

However, doing so can also destroy the “cultural mosaic” of majority South American and Caribbean neighborhoods as wealthier people move in and contribute to the areas’ “homogenization,” said Crowl, a science advisor for the mayor of Miami-Dade County.

“The social injustice part of climate is a really big deal,” said Crowl. “And it’s not something easy to wrap our heads around.”

It’s basic supply and demand: After disasters, housing costs tend to increase.

Andrew Rumbach

senior fellow at the Urban Institute

Paulette Richards has lived in Liberty City since 1977. She said she has friends whose family members are sleeping on their couches or air mattresses after being unable to afford fast-rising housing costs.

“The rent is so high,” said Richards, a community activist who’s credited with coining the term “climate gentrification.” “They cannot afford it.”

Richards, who founded the nonprofit Women in Leadership Miami and the Liberty City Climate & Me youth education program, said she began to notice more interest from “predatory” real estate developers in higher-elevation communities starting around 2010.

She said she doesn’t have a problem with development in Liberty City, in and of itself. “I want [the neighborhood] to look good,” she said. “But I don’t want it to look good for someone else.”

It’s ‘about fiscal opportunity’

Carl Juste at his photo studio in Little Haiti.

Greg Iacurci

Carl Juste’s roots in Little Haiti run deep.

The photojournalist has lived in the neighborhood, north of downtown Miami, since the early 1970s.

A mural of Juste’s parents — Viter and Maria Juste, known as the father and mother of Little Haiti — welcomes passersby outside Juste’s studio off Northeast 2nd Avenue, a thoroughfare known as an area of “great social and cultural significance to the Haitian Diaspora.”

“Anybody who comes to Little Haiti, they stop in front of that mural and take pictures,” Juste said.

A mural of Viter and Maria Juste in Little Haiti.

Greg Iacurci

A few blocks north, construction has started on the Magic City Innovation District.

The development is zoned for eight 25-story apartment buildings, six 20-story office towers, and a 420-room hotel, in addition to retail and public space, according to a webpage by Dragon Global, one of the Magic City investors. Among the properties is Sixty Uptown Magic City, billed as a collection of luxury residential units.

“Now there’s this encroachment of developers,” Juste said.

“The only place you can go is up, because the water is coming,” he said, in reference to rising seas. Development is “about fiscal opportunity,” he said.

Plaza Equity Partners, a real estate developer and one of the Magic City partners, did not respond to CNBC’s requests for comment. Another partner, Lune Rouge Real Estate, declined to comment.

Magic City development site in Little Haiti.

Greg Iacurci

But company officials in public comments have said the development will benefit the area.

The Magic City project “will bring more jobs, create economic prosperity and preserve the thriving culture of Little Haiti,” Neil Fairman, founder and chairman of Plaza Equity Partners, said in 2021.

Magic City developers anticipate it will create more than 11,680 full-time jobs and infuse $188 million of extra annual spending into the local economy, for example, according to a 2018 economic impact assessment by an independent firm, Lambert Advisory. Likewise, Miami-Dade County estimated that a multimillion-dollar initiative launched in 2015 to “revitalize” part of Liberty City with new mixed-income developments would create 2,290 jobs.

Magic City investors also invested $31 million in the Little Haiti Revitalization Trust, created and administered by the City of Miami to support community revitalization in Little Haiti.

Affordable housing and homeownership, local small business development, local workforce participation and hiring programs, community beautification projects, and the creation and improvement of public parks are among their priorities, developers said.

Zangrillo, the Dragon Global founder, sees such investment as going “above and beyond” to ensure Little Haiti is benefited by the development rather than gentrified. He also helped fund a $100,000 donation to build a technology innovation center at the Notre Dame d’Haiti Catholic Church, he said.

Developers also didn’t force out residents, Zangrillo said, since they bought vacant land and abandoned warehouses to construct Magic City.

But development has already caused unsustainable inflation for many longtime Little Haiti residents, Juste said. Often, there are other, less quantifiable ills, too, such as the destruction of a neighborhood’s feel and identity, he said.

“That’s what makes [gentrification] so perilous,” he said. “Exactly the very thing that brings [people] here, you’re destroying.”

You may like

Personal Finance

Trump admin seeks Education Department layoff ban lifted

Published

14 hours agoon

June 6, 2025

A demonstrator speaks through a megaphone during a Defend Our Schools rally to protest U.S. President Donald Trump’s executive order to shut down the U.S. Department of Education, outside its building in Washington, D.C., U.S., March 21, 2025.

Kent Nishimura | Reuters

The Trump administration on Friday asked the Supreme Court to lift a court order to reinstate U.S. Department of Education employees the administration had terminated as part of its efforts to dismantle the agency.

Officials for the administration are arguing to the high court that U.S. District Judge Myong Joun in Boston didn’t have the authority to require the Education Department to rehire the workers. More than 1,300 employees were affected by the mass layoffs.

The staff reduction “effectuates the Administration’s policy of streamlining the Department and eliminating discretionary functions that, in the Administration’s view, are better left to the States,” Solicitor General D. John Sauer wrote in the filing.

A federal appeals court had refused on Wednesday to lift the judge’s ruling.

In his May 22 preliminary injunction, Joun pointed out that the staff cuts led to the closure of seven out of 12 offices tasked with the enforcement of civil rights, including protecting students from discrimination on the basis of race and disability.

Meanwhile, the entire team that supervises the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, was also eliminated, the judge said. (Around 17 million families apply for college aid each year using the form, according to higher education expert Mark Kantrowitz.)

The Education Dept. announced its reduction in force on March 11 that would have gutted the agency’s staff.

Two days later, 21 states — including Michigan, Nevada and New York — filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration for its staff cuts at the agency.

After President Donald Trump signed an executive order on March 20 aimed at dismantling the Education Department, more parties sued to save the department, including the American Federation of Teachers.

This is breaking news. Please refresh for updates.

Personal Finance

Health insurance coverage losses under House GOP tax, spending bill

Published

18 hours agoon

June 6, 2025

Fatcamera | E+ | Getty Images

The House tax and spending bill would push millions of Americans off health insurance rolls, as Republicans cut programs like Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act to fund priorities from President Donald Trump, including almost $4 trillion of tax cuts.

The Congressional Budget Office, a nonpartisan legislative scorekeeper, projects about 11 million people would lose health coverage due to provisions in the House bill, if enacted in its current form. It estimates another 4 million or so would lose insurance due to expiring Obamacare subsidies, which the bill doesn’t extend.

The ranks of the uninsured would swell as a result of policies that would add barriers to access, raise insurance costs and deny benefits outright for some people like certain legal immigrants.

The legislation, known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” may change as Senate Republicans now consider it. Health care cuts have proven to be a thorny issue. A handful of GOP senators — enough to torpedo the bill — don’t appear to back cuts to Medicaid, for example.

More from Personal Finance:

How debt impact of House GOP tax bill may affect consumers

3 key money moves to consider while the Fed keeps interest rates higher

How child tax credit could change as Senate debates Trump’s mega-bill

The bill would add $2.4 trillion to the national debt over a decade, CBO estimates. That’s after cutting more than $900 billion from health care programs during that time, according to the Penn Wharton Budget Model.

The cuts are a sharp shift following incremental increases in the availability of health insurance and coverage over the past 50 years, including through Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act, according to Alice Burns, associate director with KFF’s program on Medicaid and the uninsured.

“This would be the biggest retraction in health insurance that we’ve ever experienced,” Burns said. “That’s makes it really difficult to know how people, providers, states, would react.”

Here are the major ways the bill would increase the number of uninsured.

No population ‘safe’ from proposed Medicaid cuts

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., pictured at a press conference after the House narrowly passed a bill forwarding President Donald Trump’s agenda on May 22 in Washington, DC.

Kevin Dietsch | Getty Images

Federal funding cuts to Medicaid will have broad implications, experts say.

“No population, frankly, is safe from a bill that cuts more than $800 billion over 10 years from Medicaid, because states will have to adjust,” said Allison Orris, senior fellow and director of Medicaid policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The provision in the House proposal that would lead most people to lose Medicaid and therefore become uninsured would be new work requirements that would apply to states that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, according to Orris.

The work requirements would affect eligibility for individuals ages 19 to 64 who do not have a qualifying exemption. Affected individuals would need to demonstrate they worked or participated in qualifying activities for at least 80 hours per month.

States would also need to verify that applicants meet requirements for one or more consecutive months prior to coverage, while also conducting redeterminations at least twice per year to ensure individuals who are already covered still comply with the requirements.

In a Sunday interview with NBC News’ “Meet the Press,” House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., said “4.8 million people will not lose their Medicaid coverage unless they choose to do so,” while arguing the work requirements are not too “cumbersome.”

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated the work requirements would prompt 5.2 million adults to lose federal Medicaid coverage. While some of those may obtain coverage elsewhere, CBO estimates the change would increase the number of people without insurance by 4.8 million.

Those estimates may be understated because they do not include everyone who qualifies but fails to properly report their work hours or submit the appropriate paperwork if they qualify for an exemption, said KFF’s Burns.

Overall, 10.3 million would lose Medicaid, which would lead to 7.8 million people losing health insurance, Burns said.

Proposal creates state Medicaid funding challenges

Protect Our Care supporters display “Hands Off Medicaid” message in front of the White House ahead of President Trump’s address to Congress on March 4 in Washington, D.C.

Paul Morigi | Getty Images Entertainment | Getty Images

While states have used health care provider taxes to generate funding for Medicaid, the House proposal would put a stop to using those levies in the future, Orris noted.

Consequently, with less revenue and federal support, states will face the tough choice of having to cut coverage or cut other parts of their state budget in order to maintain their Medicaid program, Orris said.

For example, home and community-based services could face cuts to preserve funding for mandatory benefits like inpatient and outpatient hospital care, she said.

The House proposal would also delay until 2035 two Biden-era eligibility rules that were intended to make Medicaid enrollment and renewal easier for people, especially older adults and individuals with disabilities, Burns said.

States would also have their federal matching rate for Medicaid expenditures reduced if they offer coverage to undocumented immigrants, she said.

Affordable Care Act cuts ‘wonky’ but ‘consequential’

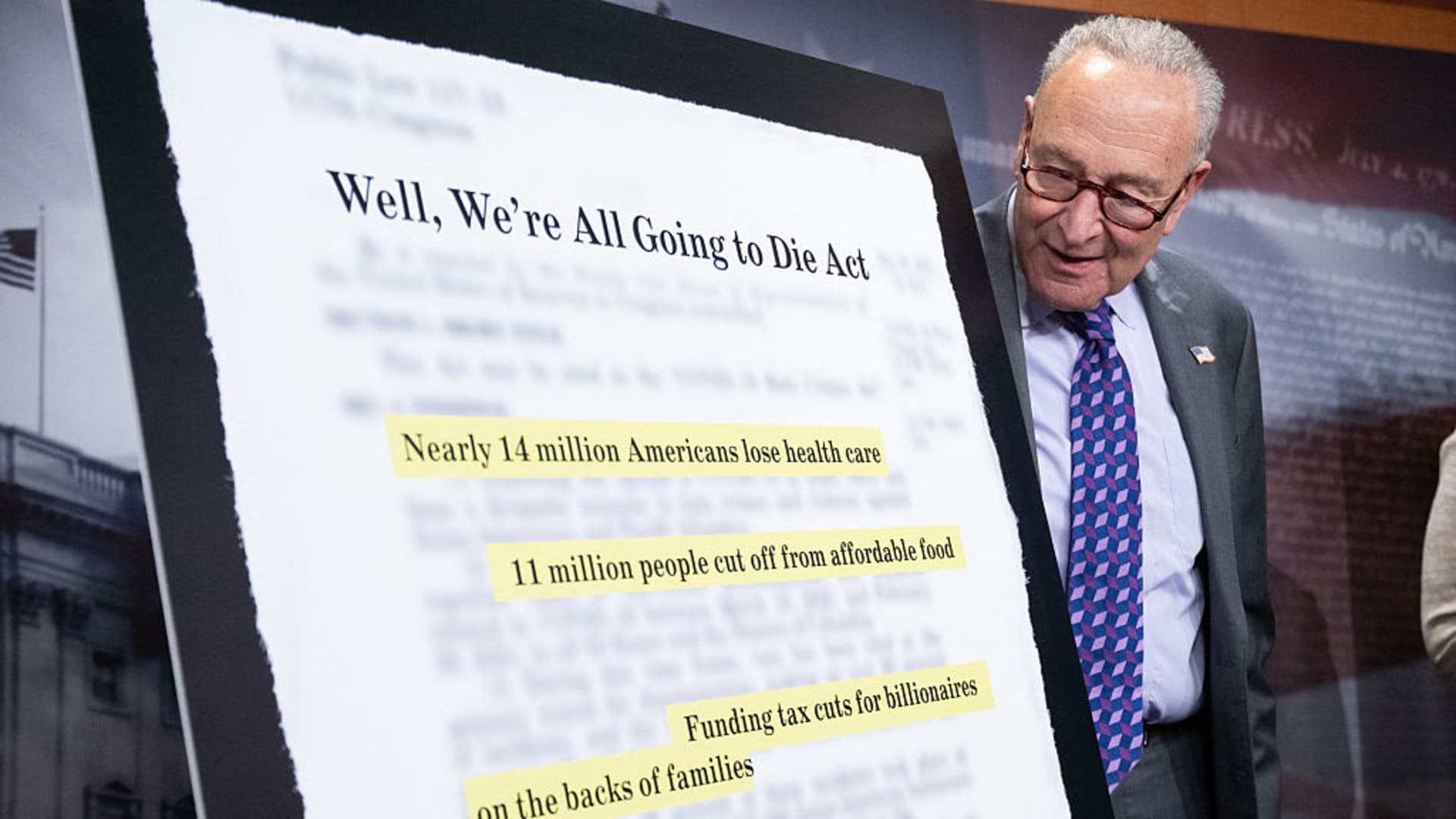

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., speaks about the health care impacts of the Republican budget and policy bill, also known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” during a June 4 news conference in Washington, D.C.

Saul Loeb | Afp | Getty Images

More than 24 million people have health insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplaces.

They’re a “critical” source of coverage for people who don’t have access to health insurance at their jobs, including for the self-employed, low-paid workers and older individuals who don’t yet qualify for Medicare, according to researchers at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-leaning think tank.

The House legislation would “dramatically” reduce ACA enrollment — and, therefore, the number of people with insurance — due to the combined effect of several changes rather than one big proposal, wrote Drew Altman, president and chief executive of KFF, a nonpartisan health policy group.

“Many of the changes are technical and wonky, even if they are consequential,” Altman wrote.

Expiring ACA subsidies add to coverage costs

ACA enrollment is at an all-time high. Enrollment has more than doubled since 2020, which experts largely attribute to enhanced insurance subsidies offered by Democrats in the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021 and then extended through 2025 by the Inflation Reduction Act.

Those subsidies, called “premium tax credits,” effectively reduce consumers’ monthly premiums. (The credits can be claimed at tax time, or households can opt to get them upfront via lower premiums.)

Congress also expanded the eligibility pool for subsidies to more middle-income households, and reduced the maximum annual contribution households make toward premium payments, experts said.

The enhanced subsidies lowered households’ premiums by $705 (or 44%) in 2024 — to $888 a year from $1,593, according to KFF.

The House Republican legislation doesn’t extend the enhanced subsidies, meaning they’d expire after this year.

About 4.2 million people will be uninsured in 2034 if the expanded premium tax credit expires, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

“They might just decide not to get [coverage] because they simply can’t afford to insure themselves,” said John Graves, a professor of health policy and medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Coverage will become more expensive for others who remain in a marketplace plan: The typical family of four with income of $65,000 will pay $2,400 more per year without the enhanced premium tax credit, CBPP estimates.

Adding red tape to eligibility, enrollment

More than 3 million people are expected to lose Affordable Care Act coverage as a result of other provisions in the House legislation, CBO projects.

Other “big” changes include broad adjustments to eligibility, said Kent Smetters, professor of business economics and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

For example, the bill shortens the annual open enrollment period by about a month, to Dec. 15, instead of Jan. 15 in most states.

It ends automatic re-enrollment into health insurance — used by more than half of people who renewed coverage in 2025 — by requiring all enrollees to take action to continue their coverage each year, CBPP said.

Senate Majority Leader Sen. John Thune (R-SD) (C) speak alongside Sen. John Barrasso (R-WY) (L) and Sen. Mike Crapo (R-ID) (R) outside the White House on June 4, 2025. The Senators met with President Donald Trump to discuss Trump’s “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” and the issues some members within the Republican Senate have with the legislation and its cost.

Anna Moneymaker | Getty Images News | Getty Images

The bill also bars households from receiving subsidies or cost-sharing reductions until after they verify eligibility details like income, immigration status, health coverage status and place of residence, according to KFF.

Graves says adding administrative red tape to health plans is akin to driving an apple cart down a bumpy road.

“The bumpier you make the road, the more apples will fall off the cart,” he said.

Uncapping subsidy repayments

Another biggie: The bill would eliminate repayment caps for premium subsidies.

Households get federal subsidies by estimating their annual income for the year, which dictates their total premium tax credit. They must repay any excess subsidies during tax season, if their annual income was larger than their initial estimate.

Current law caps repayment for many households; but the House bill would require all premium tax credit recipients to repay the full amount of any excess, no matter their income, according to KFF.

While such a requirement sounds reasonable, it’s unreasonable and perhaps even “cruel” in practice, said KFF’s Altman.

“Income for low-income people can be volatile, and many Marketplace consumers are in hourly wage jobs, run their own businesses, or stitch together multiple jobs, which makes it challenging, if not impossible, for them to perfectly predict their income for the coming year,” he wrote.

Curtailing use by immigrants

The House bill also limits marketplace insurance eligibility for some groups of legal immigrants, experts said.

Starting Jan. 1, 2027, many lawfully present immigrants such as refugees, asylees and people with Temporary Protected Status would be ineligible for subsidized insurance on ACA exchanges, according to KFF.

Additionally, the bill would bar Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipients in all states from buying insurance over ACA exchanges.

DACA recipients — a subset of the immigrant population known as “Dreamers” — are currently considered “lawfully present” for purposes of health coverage. That makes them eligible to enroll (and get subsidies and cost-sharing reductions) in 31 states plus the District of Columbia.

PUNTA GORDA – OCTOBER 10: In this aerial view, a person walks through flood waters that inundated a neighborhood after Hurricane Milton came ashore on October 10, 2024, in Punta Gorda, Florida. The storm made landfall as a Category 3 hurricane in the Siesta Key area of Florida, causing damage and flooding throughout Central Florida. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Joe Raedle | Getty Images News | Getty Images

It’s officially hurricane season, and early forecasts indicate it’s poised to be an active one.

Now is the time to take a look at your homeowners insurance policy to ensure you have enough and the right kinds of coverage, experts say — and make any necessary changes if you don’t.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts a 60% chance of “above-normal” Atlantic hurricane activity during this year’s season, which spans from June 1 to November 30.

The agency forecasts 13 to 19 named storms with winds of 39 mph or higher. Six to 10 of those could become hurricanes, including three to five major hurricanes of Category 3, 4, or 5.

You should pay close attention to your insurance policies.

Charles Nyce

risk management and insurance professor at Florida State University

Hurricanes can cost billions of dollars worth of damages. Experts at AccuWeather estimate that last year’s hurricane season cost $500 billion in total property damage and economic loss, making the season “one of the most devastating and expensive ever recorded.”

“Take proactive steps now to make a plan and gather supplies to ensure you’re ready before a storm threatens,” Ken Graham, NOAA’s national weather service director, said in the agency’s report.

Part of your checklist should include reviewing your insurance policies and what coverage you have, according to Charles Nyce, a risk management and insurance professor at Florida State University.

“Besides being ready physically by having your radio, your batteries, your water … you should pay close attention to your insurance policies,” said Nyce.

More from Personal Finance:

How child tax credit could change as Senate debates Trump’s mega-bill

This map shows where seniors face longest drives

Some Social Security checks to be smaller in June from student loan garnishment

You want to know four key things: the value of property at risk, how much a loss could cost you, whether you’re protected in the event of flooding and if you have enough money set aside in case of emergencies, he said.

Bob Passmore, the department vice president of personal lines at the American Property Casualty Insurance Association, agreed: “It’s really important to review your policy at least annually, and this is a good time to do it.”

Insurers often suspend policy changes and pause issuing new policies when there’s a storm bearing down. So acting now helps ensure you have the right coverage before there’s an urgent need.

Here are three things to consider about your home insurance policy going into hurricane season, according to experts.

1. Review your policy limits

First, take a look at your policy’s limits, which represents the highest amount your insurance company will pay for a covered loss or damage, experts say. You want to make sure the policy limit is correct and would cover the cost of rebuilding your home, Passmore said.

Most insurance companies will calculate the policy limit by taking into account the size of your home and construction costs in your area, said Nyce. For example, if you have a 2,000 square foot home, and the cost of construction in your area is $250 per square foot, your policy limit would need to be $500,000, he said.

You may risk being underinsured, however, especially if you haven’t reviewed your coverage in a while. Rising building costs or home renovations that aren’t reflected in your insurer’s calculation can mean your coverage lags the home’s replacement value.

Repair and construction costs have increased in recent years, experts say. In the last five years, the cost of construction labor has increased 36.3% while the building material costs are up 42.7%, the APCIA found.

Most insurance companies follow what’s called the 80% rule, meaning your coverage needs to be at least 80% of its replacement cost. If you’re under, you risk your insurer paying less than the full claim.

2. Check your deductibles

Take a look at your deductibles, or the amount you have to pay out of pocket upfront if you file a claim, experts say.

For instance, if you have a $1,000 deductible on your policy and submit a claim for $8,000 of storm coverage, your insurer will pay $7,000 toward the cost of repairs, according to a report by NerdWallet. You’re responsible for the remaining $1,000.

A common way to lower your policy premium is by increasing your deductibles, Passmore said.

Raising your deductible from $1,000 to $2,500 can save you an average 12% on your premium, per NerdWallet’s research.

But if you do that, make sure you have the cash on hand to absorb the cost after a loss, Passmore said.

Don’t stop at your standard policy deductible. Look over hazard-specific provisions such as a wind deductible, which is likely to kick in for hurricane damage.

Wind deductibles are an out-of-pocket cost that is usually a percentage of the value of your policy, said Nyce. As a result, they can be more expensive than your standard deductible, he said.

If a homeowner opted for a 2% deductible on a $500,000 house, their out-of-pocket costs for wind damages can go up to $10,000, he said.

“I would be very cautious about picking larger deductibles for wind,” he said.

3. Assess if you need flood insurance

Floods are usually not covered by a homeowners insurance policy. If you haven’t yet, consider buying a separate flood insurance policy through the National Flood Insurance Program by the Federal Emergency Management Agency or through the private market, experts say.

It can be worth it whether you live in a flood-prone area or not: Flooding causes 90% of disaster damage every year in the U.S., according to FEMA.

In 2024, Hurricane Helene caused massive flooding in mountainous areas like Asheville in Buncombe County, North Carolina. Less than 1% of households there were covered by the NFIP, according to a recent report by the Swiss Re Institute.

If you decide to get flood insurance with the NFIP, don’t buy it at the last minute, Nyce said. There’s usually a 30-day waiting period before the new policy goes into effect.

“You can’t just buy it when you think you’re going to need it like 24, 48 or 72 hours before the storm makes landfall,” Nyce said. “Buy it now before the storms start to form.”

Make sure you understand what’s protected under the policy. The NFIP typically covers up to $250,000 in damages to a residential property and up to $100,000 on the contents, said Loretta Worters, a spokeswoman for the Insurance Information Institute.

If you expect more severe damage to your house, ask an insurance agent about excess flood insurance, Nyce said.

Such flood insurance policies are written by private insurers that cover losses over and above what’s covered by the NFIP, he said.

XcelLabs launches to help accountants use AI

Accounting is changing, and the world can’t wait until 2026

Republicans push Musk aside as Trump tax bill barrels forward

New 2023 K-1 instructions stir the CAMT pot for partnerships and corporations

The Essential Practice of Bank and Credit Card Statement Reconciliation

Are American progressives making themselves sad?

Trending

-

Blog Post6 days ago

Blog Post6 days agoCommon Bookkeeping Challenges and Solutions for Small Businesses

-

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week agoHighest paid jobs in corporate accounting

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoElon Musk says Trump’s spending bill undermines the work DOGE has been doing

-

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week agoWhy the president must not be lexicographer-in-chief

-

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week agoHarvard, Trump international enrollment battle affects college applicants

-

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week agoCrypto in 401(k) plans: Trump administration eases rules

-

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week agoTrump to pardon stars of reality show ‘Chrisley Knows Best’

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoVail Resorts, GameStop and more