A Social Security Administration office in Washington, D.C., March 26, 2025.

Saul Loeb | Afp | Getty Images

A new Social Security Administration policy will require nearly 2 million additional beneficiaries to visit the agency’s offices each year to change their direct deposit information, according to agency estimates.

That’s often not a quick trip: Nearly one-quarter of seniors live more than an hour away from their local Social Security field office, according to a new analysis from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Meanwhile, half of seniors need to drive for at least 33 minutes without traffic to get to their Social Security office.

The policy change will lead to more than 1 million hours of travel per year, according to the nonpartisan policy and research institute.

Why more people need to visit Social Security offices

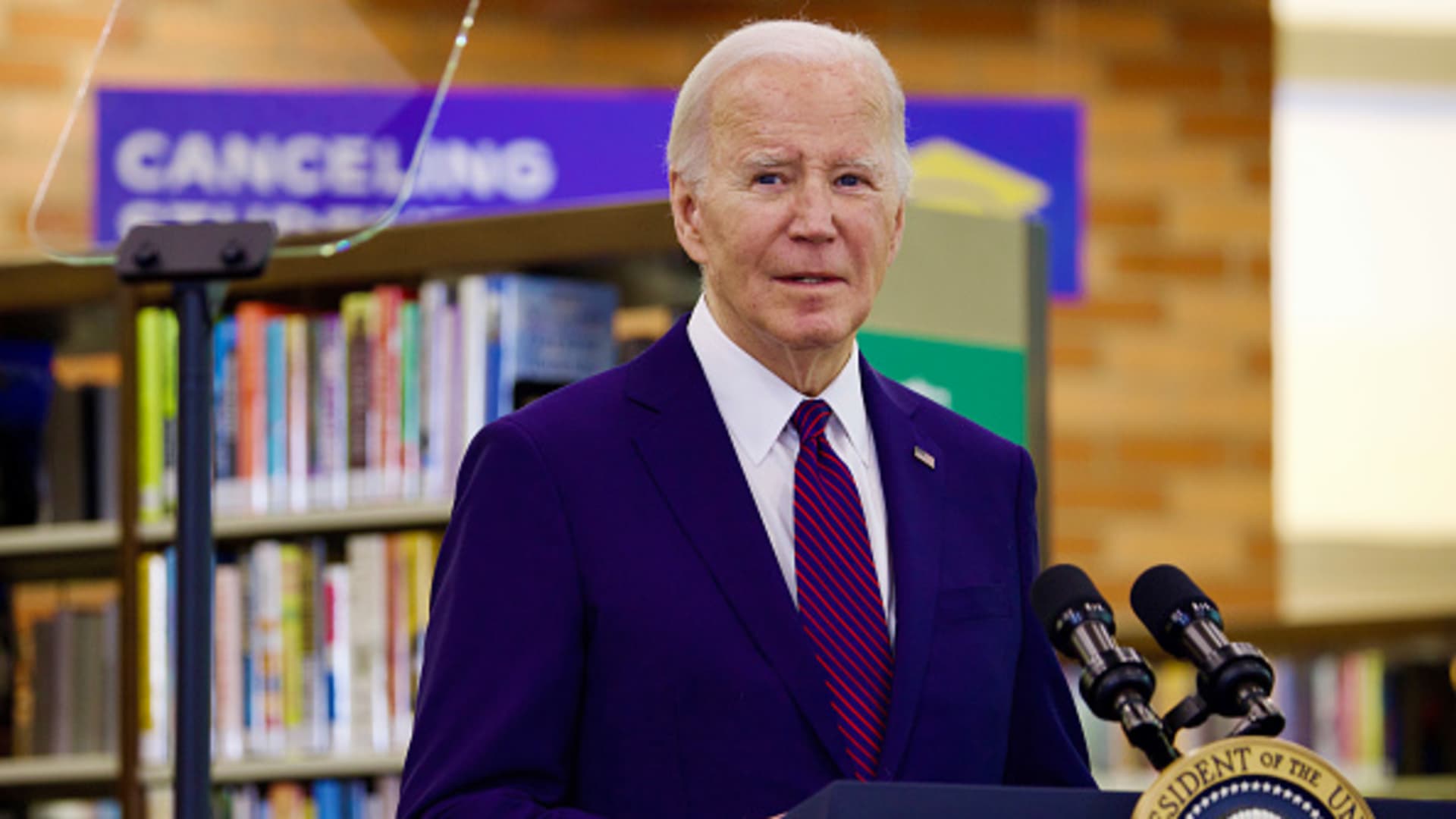

The Social Security Administration said the new direct deposit requirements would curb fraud, which it said it’s been working to root out in coordination with the Trump administration’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency.

Since 2023, the agency has experienced a “marked increase” in allegations of direct deposit fraud, a Social Security Administration official said via email.

In March, SSA implemented enhanced fraud protection for direct deposit changes. Between March 29 and April 26, the enhanced fraud protection flagged more than 20,000 Social Security numbers where phone direct deposit requests failed security measures that check for multiple fraud indicators.

Of the direct deposit transactions flagged, 61% to 72% of individuals never resubmitted their requests, a “strong indicator” that many of those attempts may not have been legitimate, according to the SSA official.

The agency estimates $19.9 million in losses were avoided as a result of the enhanced safety measures.

However, advocates say the change is an overreaction, given the scale of such fraud. The Social Security Administration has said about 40% of direct deposit fraud comes from phone calls attempting to change direct deposit information.

In early 2024, anti-fraud officials at the agency told The New York Times that about 2,000 beneficiaries had their direct deposits redirected over the prior year. By those estimates, that would mean just 800 of those people experienced direct deposit fraud by phone, according to Kathleen Romig, director of Social Security and disability policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Yet the agency is now requiring about 2 million elderly and disabled individuals to visit its offices to prevent such fraud, she said.

More from Personal Finance:

What the House GOP budget bill means for your money

Trump tariffs create the ‘perfect storm’ for scams

Social Security COLA for 2026 projected to be lowest in years

To help ensure benefit payments are not misdirected, the Social Security Administration has tightened beneficiaries’ ability to change their bank information over the phone.

As of April 28, individuals who want to change their direct deposit information will need to log into or create a personal My Social Security online account and obtain a one-time code before they call the agency’s 800 number.

Individuals who cannot use online or automatic enrollment services will need to visit a local field office to verify their identity in person. While the agency encourages those individuals to make an appointment, it is also possible to walk in for direct deposit changes.

Individuals who want to change their direct deposit information may also use automatic enrollment services through their bank. To do so, individuals need to contact their bank directly. Not all financial institutions participate in this process, according to SSA.

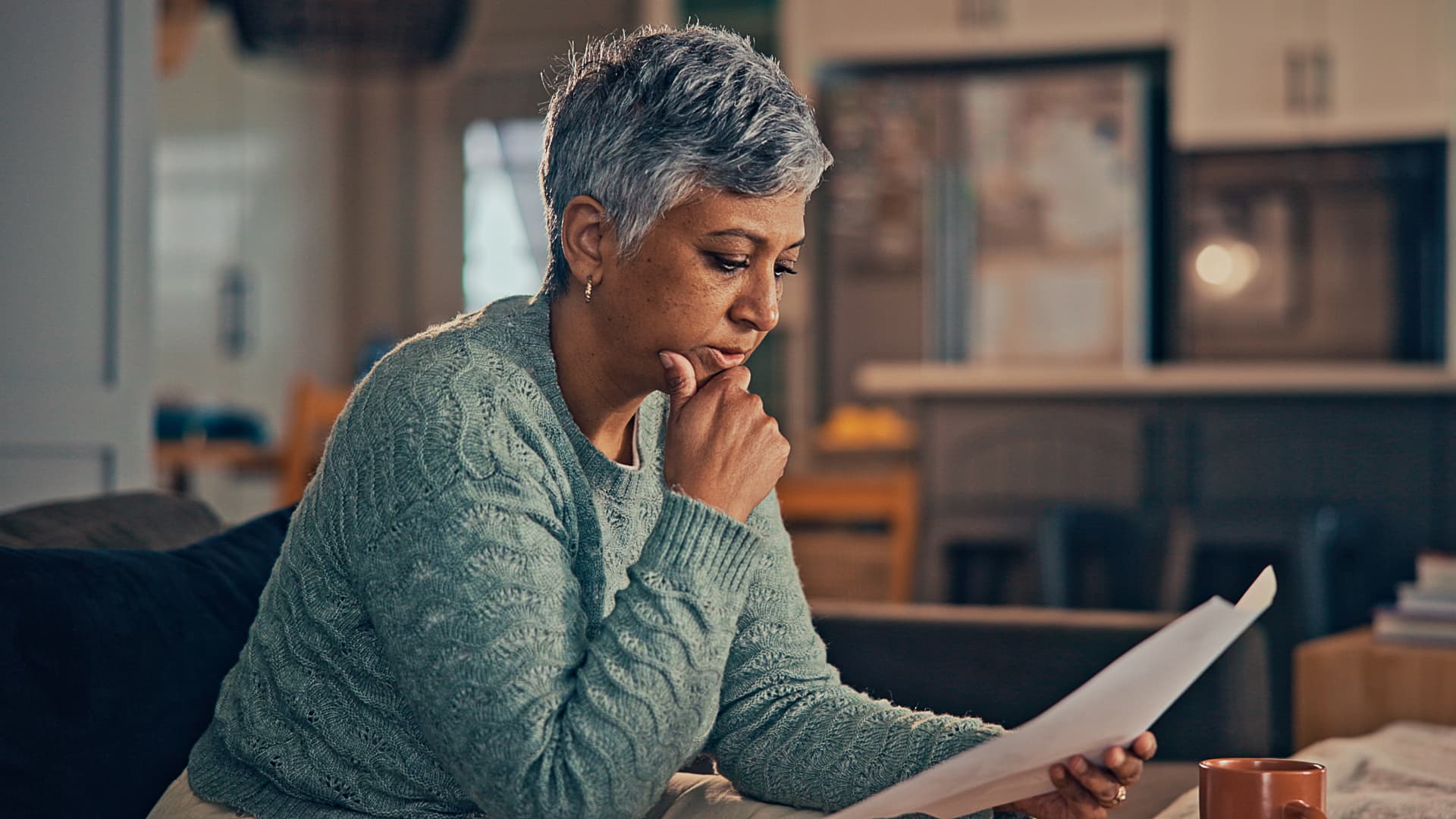

Because many seniors or disabled individuals do not have internet service, computers or smart phones — or if they do, may not know how to use those resources — many will likely have to make an in-person visit to their local Social Security office.

About 6 million seniors don’t drive, while almost 8 million older Americans have a medical condition or disability that makes it difficult for them to travel, according to CBPP research.

Where seniors may face longest drive times

In-person appointments may be burdensome for beneficiaries who face long travel times to get to their nearest Social Security office, according to the CBPP analysis.

In 31 states, more than 25% of seniors face travel times of more than an hour to get to their local field office.

In certain less-populated states, more than 40% of seniors would need to drive more than an hour. Those include Arkansas, Iowa, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont and Wyoming.

In other states, around 25% to 39% of seniors would need to travel over an hour. That includes Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Virginia.

Residents of other states may also face a burden if they do not live near their closest Social Security field office.

The analysis is a conservative estimate to help assess how much time it may cost individuals who are affected by the policy, according to Devin O’Connor, senior fellow at the CBPP.

For example, it doesn’t take into account the time spent getting an appointment to visit a Social Security office and the time spent waiting for the appointment, he said.

The CBPP’s analysis was created with information from multiple sources including the 2022 National Household Travel Survey, SSA field office location data, the OpenTimes travel time database and the Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey.

The Social Security Administration has not independently validated the data, the agency said via email in response to a request for comment.

Staffing cuts may add to appointment wait times

Notably, the new direct deposit requirements come as the Social Security Administration has moved to cut its work force by about 7,000 employees, reductions that have led some of the agency’s field offices to be “understaffed,” O’Connor said.

However, while it had been reported that DOGE planned to close Social Security field offices to help curb spending, thus far that has largely not happened, he said. The Social Security Administration has denied it plans to close local field offices.

Individuals who need to visit a Social Security field office will also be confronted by long wait times for appointments. Currently, just 43% of individuals are able to get a benefit appointment within 28 days, Social Security Administration data shows.

The agency’s new policy to limit phone transactions has been scaled back. The agency had proposed limiting the ability to apply for benefits over the phone, but after it received pushback from organizations including the AARP, the agency changed that policy to limit only direct deposit transactions.

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Blog Post1 week ago

Blog Post1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics5 days ago

Economics5 days ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Economics6 days ago

Economics6 days ago

Accounting5 days ago

Accounting5 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago