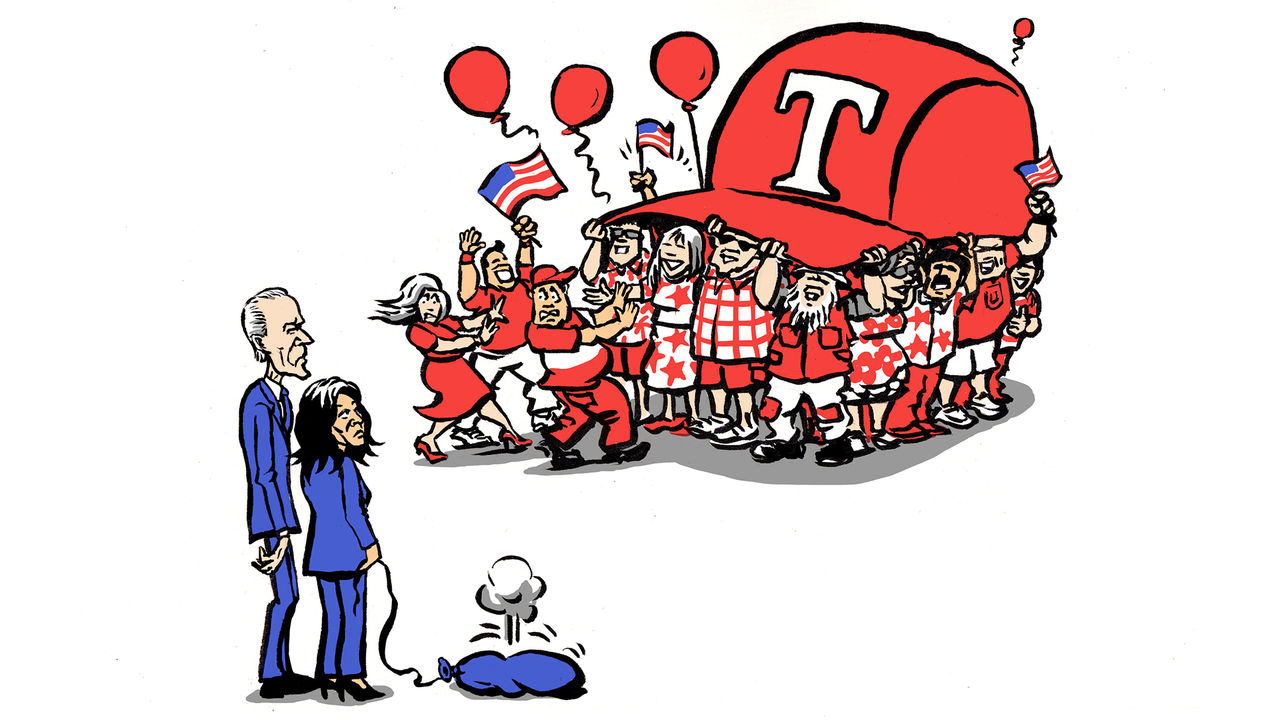

If you think Donald Trump is too crass or cruel or incompetent to be president—if you are disappointed or even astonished that, having tried and failed to subvert the will of the people in the last election, he has come back to win fair and square—you should be asking yourself this question: why, to so many Americans, does the Democratic Party seem worse?

This victory is a tremendous achievement for Mr Trump, who after his loss in 2020 and the attack on the Capitol on January 6th 2021 was counted out even by leaders of his own party. At the time Mitch McConnell, the Senate Republican leader, who privately regarded Mr Trump as “a sleazeball” and “stupid”, called the insurrection “further evidence of Donald Trump’s complete unfitness for office”, according to reporting he has not disputed in a new biography by Michael Tackett, a journalist.

Yet what might seem a psychological frailty—an inability to brook criticism or concede mistakes, much less defeat—has for Mr Trump been a mighty source of political strength, one that intensifies his connection to the voters he has made the base of the Republican Party. As in 2016, Mr Trump wielded his command of that bloc of voters this year to clear a path through crowded Republican primaries, and then relied upon “negative polarisation”, or fear of the other guys, to unite the party. “Can you believe he endorsed me?” Mr Trump chortled at a rally in North Carolina on November 3rd, gloating over how Mr McConnell eventually fell into line. Mr Trump felt no obligation to reciprocate. “Hopefully we get rid of Mitch McConnell pretty soon,” he said.

Mr Trump has shown courage, not only in weathering assassins’ attacks but in insisting on views on trade, entitlements and other matters that a few years ago were heresy within his party. With his sophisticated grasp of new and legacy media and his instinct for the basic needs and fears of many Americans, he has revolutionised how American politics is conducted and shifted the policy terrain over which it is waged. In terms of disrupting what came before, he has had more effect than even Ronald Reagan.

Unlike Reagan—or the other two-term presidents since, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama—Mr Trump has never been very popular, though he managed, in this third run as the Republican nominee, at last to win the popular vote. Unlike those predecessors, Mr Trump has relied upon division, not addition, for his electoral maths. In his first term his average approval rating of 41% was the lowest ever measured by the Gallup Poll, which began tracking the statistic under Harry Truman. Democrats have good reason to think Mr Trump repels many voters when he calls adversaries “vermin” or “the enemy from within” or says illegal immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country”.

Yet, after this victory, whatever disdain Democrats have for Mr Trump should be cause only for humility and self-scrutiny. As in 2016, Mr Trump’s broad support will present his adversaries with a Rorschach test in which they can see their preferred image of America, and it will be ugly. For some, white supremacy and misogyny will explain Mr Trump’s success, while others may attribute it to tax cuts and greed. Some will conclude that poor, non-white or female Americans have been ensorcelled into voting against their self-interest. Rather than retreat into some grand theory, they would so better ro think through how, in a divided country, President Joe Biden might have nudged the balance a few points away from Mr Trump, rather than to him. Kamala Harris was no bystander, but pime responsibility lies with the president she served.

Mr Biden did not heed his own warnings about Mr Trump. He tried to eat into Mr Trump’s support with blue-collar workers through giant investments in manufacturing and infrastructure that offered something to everyone. But, unlike Mr Clinton or Mr Obama, he ducked choices that would have respected the concerns of most Americans but disappointed left-wing Democrats. A political strategy of addition still requires some division.

Most egregious, Mr Biden resharpened Mr Trump’s most effective political wedge by doing away with obstacles he had created to illegal immigration, with no alternative. By the time he restored some of Mr Trump’s restrictions this spring, more than 4m migrants had crossed the southern border, compared with fewer than 1m under Mr Trump. That was terrible for the Democrats as a party, and worse for people they want to help and the cause they believe in: under Mr Biden, Americans who say they want a decrease in legal immigration rose from a minority to a majority, as did the number who favour mass deportation.

How to defend democracy

Even where Mr Biden had accomplishments that undermined Mr Trump’s arguments, he let himself be constrained by his party’s loudest activists. Oil production rose to record levels, but Mr Biden did not boast about that. He was also no longer up to the demands of presidential communication that Mr Trump understands so well. He was not constantly, energetically promoting his success in sustaining economic growth and raising wages. His approval rating sagged as low as 36% just asother Democrats were forcing him to face the obvious: he should not be running again. In the short time Ms Harris had, she waged a good campaign. But any politician would have struggled under such burdens. She could not separate herself enough from Mr Biden, or from the video Mr Trump’s ads used, to devastating effect, of her recently declaring positions that were alienating to most Americans.

“We have learned again that democracy is precious,” Mr Biden proudly declared during his inaugural address almost four years ago. “Democracy is fragile. And at this hour, my friends, democracy has prevailed.” Now it has prevailed again. Will Democrats get the message this time? ■

Blog Post7 days ago

Blog Post7 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago