Standing in front of a few dozen Democratic Party members in a shopfront in Ypsilanti, a town just south-east of Ann Arbor, Debbie Dingell, a congresswoman from Michigan, delivers the bad news. “None of you believed me in 2016 when I said that Donald Trump could win,” she says. “Too many people don’t know why we gotta elect Joe Biden. We aren’t talking about what he’s gotten done the last four years.” She then goes on to list half a dozen reasons why Mr Biden’s re-election is crucial, starting with the environment, women’s reproductive rights, the economy, health care and then finally, how Donald Trump is “splitting Americans apart” with his violent rhetoric. “It’s more important now than it’s ever been to turn out the votes,” she concludes. “Ground Zero is right here right now.”

Ms Dingell was speaking at the opening of one of 30 campaign offices that Mr Biden’s campaign will soon have operating across the Wolverine State, a decisive swing state during the past two presidential elections. In 2016 Mr Trump won Michigan with a margin of just 0.3%. In 2020 Mr Biden took it back for the Democrats by 2.8%. State Democratic officials are confident that they can repeat the trick this year, and they cite a remarkable campaigning machine built since 2017 as evidence. “We are organising and talking to voters all the time,” says Lavora Barnes, the Democratic chairwoman. But Ms Dingell’s warning rings true too. Michigan is thus a good place to take the pulse of Mr Biden’s campaign. The president is running a traditional playbook, while Mr Trump’s approach to electioneering is as unconventional as ever.

Ms Barnes is right that Democrats have a significant organisational advantage over their opponents. Nationwide Mr Biden’s campaign committee has raised $129m to $96m raised by Mr Trump, and the cash is flowing into Michigan. As well as opening offices, the party is hiring staffers at pace. Phenomenally peppy 20-somethings are moving from all over the country to take up campaign jobs. An army of pensioners with lots of free time is already equipped with yard signs and bumper stickers to distribute to their neighbours.

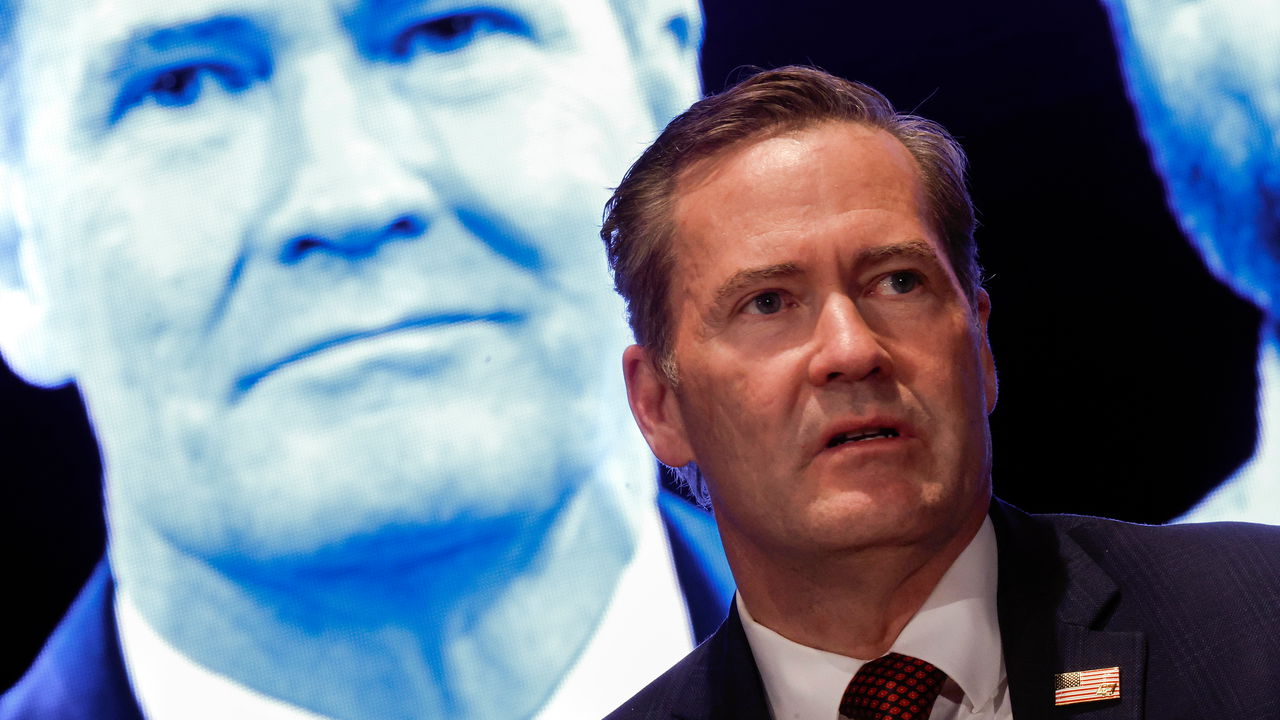

By contrast, Mr Trump’s campaign is far less visible. On April 2nd the former president held a modest rally in Grand Rapids, attended mostly by journalists and local Republican officials. But the campaign is only now “putting in place the building blocks” of its organisation, says Pete Hoekstra, the party chairman. “We are not counting offices,” he says, when asked if any have opened yet. For much of the past year, Michigan Republicans have been in disarray. In January members voted to oust their chair, Kristina Karamo, a vocal proponent of the theory that the 2020 election was rigged, over complaints that she was mismanaging the party and its finances. In the end it took a lawsuit to get her to step down. At one point last year a dispute between two party officials ended in a physical fight, with a county chairman apparently complaining that a fellow activist had “kicked me in my balls”.

Yet a ground-game advantage does not guarantee that Mr Biden will win the state. Most evidence from political science suggests that door-knocking has at most a marginal effect, generally by boosting turnout. It certainly cannot replace a persuasive message. The early campaign suggests that Democrats may have too many points to make and have yet to craft a unified argument.

Take for example the talking points of Gretchen Whitmer, Michigan’s popular Democratic governor. Asked at another office opening, this one in Livingston County, a Republican-leaning suburb north-west of Detroit, what she expects the message of the election to be, at first she replies frankly: “Everything’s about the economy.” But then she adds: “Our ability to make our own decisions about our body, when and whether or not to bear a child, that is the most important economic decision a woman will make over the course of her lifetime.” In addition, she continues, education and climate change matter, as does “onshoring supply chains”. These things, she says, are “all going to be absolutely central to what’s on voters’ minds.”

The breadth of the message reflects the challenge Democrats face in Michigan, particularly at presidential level. To beat Mr Trump, the party needs to make sure that committed Democrats turn out in large numbers, particularly in the state’s urban strongholds in Detroit and Ann Arbor. Already that base is rather divided. It includes college students, black blue-collar workers, white professionals, the liberal elderly and the more unionised of the white working class. A few older activists in Livingston mentioned unprompted their disdain for digital campaigning, arguing that it doesn’t persuade anyone new. By contrast, young voters are deeply online. “I really think that a lot more people now get their beliefs based off of, like, Instagram and TikTok,” says Jacob Welch, the president of Michigan’s College Democrats organisation. He worries that Mr Biden’s support for Israel in Gaza is putting young voters off.

What unites the base most is, as Mr Welch puts it, that they all “despise Donald Trump”. But the party also needs to win over at least a few people who might be tempted to vote for him. Ms Barnes says that one of the reasons Hillary Clinton lost the state in 2016 was that she prioritised making sure solid Democrats turned out to vote, and neglected trying to persuade people on the fence. “There was a lot of focus on just turnout,” particularly in big cities, she says. Now they are trying to reach areas Democrats don’t usually touch—hence the opening of offices in places like Livingston. “I think that there are a lot of fair-minded, thoughtful folks who have voted Republican in the past,” she says.

The tricky thing is that those voters may require different messages, and sometimes they pull across each other. The voters Mr Biden needs to tempt away are also a diverse mix. They include wealthier, more socially liberal suburban Republicans but also blue-collar workers. Jacob Hilliker, the Michigan representative for LiUNA, a large trade union that represents mostly workers in the construction trade, and which has endorsed Mr Biden, says the case for Mr Biden for his union members is that “he’s done nothing but make it rain jobs like nobody has before”. When asked about the appeal of culture-war issues, such as abortion or IVF, he demurs. “I have my personal views on abortion rights, guns, the right to hunt in Michigan,” he says, without specifying what they are. “We are here to fight for jobs.”

Mr Trump’s message, by contrast, is crude but simple. “You’re under an invasion,” he told his audience in Grand Rapids. Flanked by a gaggle of sheriffs, and two television screens showing a chart of border crossings, he argued that Joe Biden is letting criminal “illegal aliens” and useless Chinese electric cars flood into Michigan. (He said the crime rate in Venezuela has fallen, which is true, and suggested it is because so many wrong-uns have been sent to America, which is not.) To fix this, he proposes to whack monstrous trade tariffs on Mexico, to stop Chinese firms building cars there, and to “begin the largest domestic deportation operation in the history of our country”. For good measure he also added that he would give police officers accused of wrongdoing complete immunity from litigation.

Shawn Fain, the leader of the United Auto Workers union, says Mr Trump “is like the third-grader running for class president, you know, he wants to give a free candy machine to everybody in the class.” He points out that when the union went on strike last year, Mr Biden visited them, whereas Mr Trump, as president, shunned a strike in 2019. But even Mr Fain admits he sometimes has to work to persuade his members. “You can claim you love Trump or whatever the hell your reasoning is. And if you do that, so be it. I feel for you. But at the end of the day, facts are facts,” he says. “He’s just flat-out a con man.”

Mr Biden’s best hope is to pull all these strands together over the next seven months. In Livingston County, Dan Luria, the county party vice-chairman, adds his own ideas. Mr Biden, he says, ought to “reappropriate the concept of freedom”. Freedom, he says, ties everything together—from reproductive rights to the economy. Also, he adds, you can put out a lot of American flags. That is one bit of advice the Biden campaign is sure to follow. ■

Stay on top of American politics with The US in brief, our daily newsletter with fast analysis of the most important electoral stories, and Checks and Balance, a weekly note from our Lexington columnist that examines the state of American democracy and the issues that matter to voters.

Finance3 days ago

Finance3 days ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Finance4 days ago

Finance4 days ago

Personal Finance5 days ago

Personal Finance5 days ago

Economics5 days ago

Economics5 days ago

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance6 days ago

Personal Finance6 days ago