James Bennet, our Lexington columnist, says America neglects the Middle East at everyone’s peril

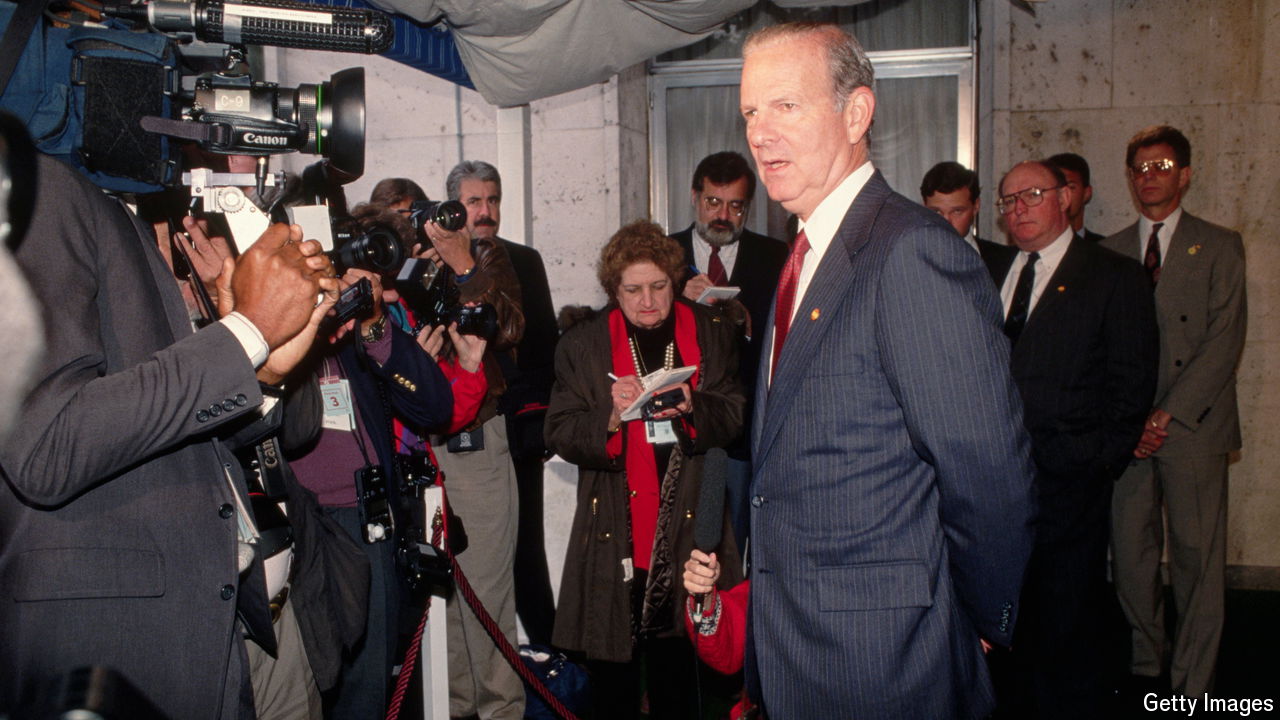

The secretary of state declared he was not going to waste his energy chasing peace among Israelis and Arabs. The region was a quagmire, he told an aide as he took office, and he was “not going to fly around the Middle East” like his predecessor. That attitude might sound familiar from the last three American administrations, but the secretary in state in question was James Baker, during the administration of President George H.W. Bush, as described by Peter Baker and Susan Glasser in their biography, “The Man Who Ran Washington”.

Mr Baker’s aide, Dennis Ross, responded to him with a warning that more recent administrations should also have heard: while Mr Baker “might want to ignore the Middle East, it would not ignore him”.

Like Donald Trump and Barack Obama, President Joe Biden came into office wanting to focus his attention on Asia. When it came to Israelis and Palestinians he stuck with the “outside-in” approach of Mr Trump, hoping that more Arab states would sign peace deals with Israel, and that that would somehow put pressure on the Palestinians eventually to strike a deal, too. As our briefing this week explains, both those goals now seem out of reach.

It was the first Gulf war that prompted Mr Baker to embark on his own round of intense Middle East peacemaking, taking at least eight trips to the region, including one three-week marathon, that led to the Madrid peace conference in 1991. He did not achieve a peace deal; as Mr Ross had also warned him, he would need “heroes for dramatic breakthroughs”, leaders like Anwar Sadat of Egypt, who gave his life for peace with Israel. No such heroes were on offer.

But Madrid paved the way, as did pressure from the Bush administration that brought down a right-wing Israeli government, elevating a new prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin. During the Clinton administration, Rabin sealed the Oslo accords, the interim peace agreements between Israel and the Palestinians. Then, like Sadat, he was killed.

I’m not suggesting this war in Gaza is about to lead to some kind of reset, much less a breakthrough. But I found myself thinking about this history as I wrote this week about the public rupture between Chuck Schumer, the Senate majority leader and a champion of Israel within the Democratic Party, and Binyamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister. It seems worth thinking back on the more hopeful moments and what made them possible, including the sort of intelligent, focused attention from American peacemakers that has been missing from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for far too long.

Accounting7 days ago

Accounting7 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Accounting1 week ago

Finance6 days ago

Finance6 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago