James Bennet, our Lexington columnist, considers what the history of the Chicago national conventions teach both parties today

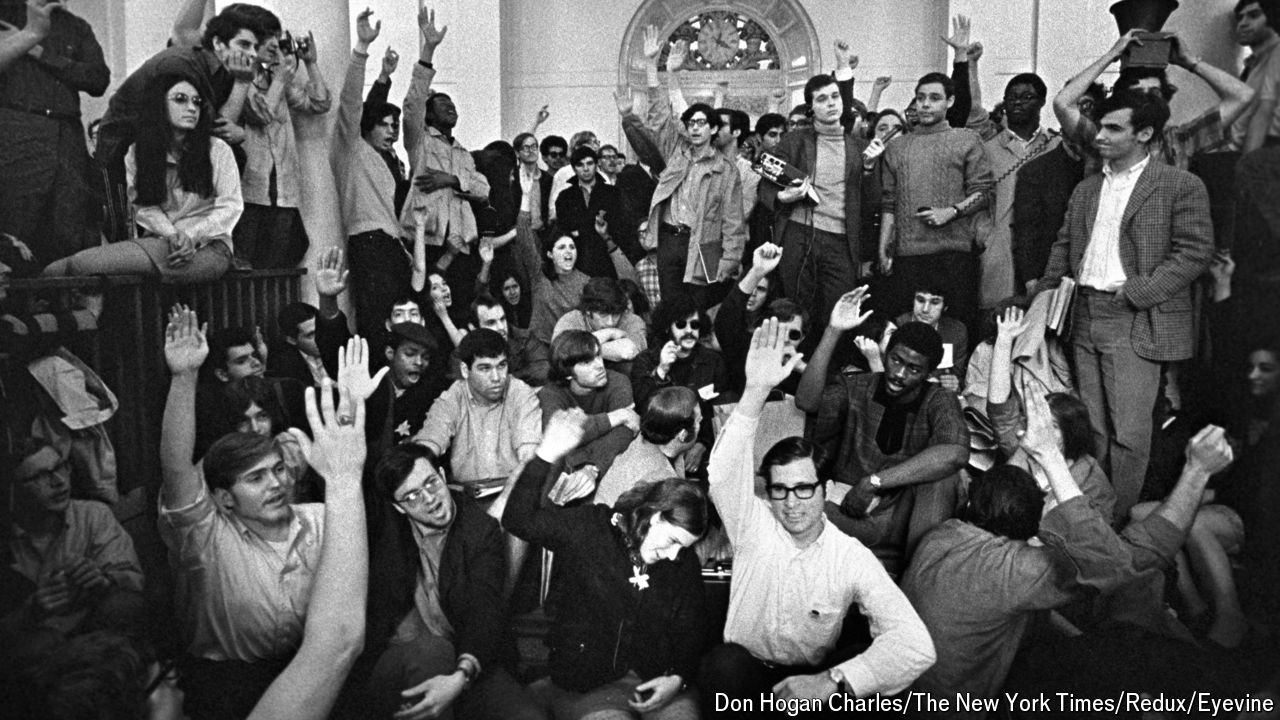

We’re all going to be hearing a lot this summer about the Democrats’ storm-tossed convention in Chicago in 1968, since the party is convening there again this August. Given the uproar on college campuses, I tried to beat the rush by writing this week about how echoes of ’68, and the anti-war protests of that year, are resounding through national politics. But so much history has been made at Chicago conventions that the violent, divisive convention of ’68 is really only one of several potential touchstones. Herewith, for both parties to consider, are some more hopeful precedents and themes.

Realising the promise of America: The first national political convention in Chicago was in 1860, and the Republicans who gathered there chose the least-known of three candidates, a former one-term congressman named Abraham Lincoln. (In another Chicago political tradition, skulduggery, Lincoln’s operatives used counterfeit tickets to pack supporters into the convention site, the Wigwam, and on the third ballot they secured him the nomination by flipping some Ohio delegates’ votes with promises of patronage, apparently without the candidate’s knowledge.)

Connecting with rural voters: In 1896, when Democrats gathered in Chicago towards the end of a deep depression, another former congressman, just 36 years old, won the nomination with perhaps the most electrifying populist speech in American history—certainly the most electrifying one about monetary policy. “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!” thundered William Jennings Bryan. (Bryan lost to William McKinley, who tapped big business for huge contributions.)

Achieving profound reform: After failing to take back the Republican nomination from William Howard Taft in Chicago in 1912, former President Theodore Roosevelt bolted to create the Progressive Party. He split the Republican vote and threw the election to the Democrat, Woodrow Wilson, but helped guide America up the path to women’s suffrage and the direct election of senators, among other changes.

Overcoming a depression, winning a world war and building an enduring coalition: Democrats picked Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt of New York on the fourth ballot in Chicago in 1932. He broke tradition by accepting the nomination in person, saying one task of the Democrats should be “to break foolish traditions”. He also, in more famous words, pledged them “to a new deal for the American people”. (It was also in Chicago that, in 1940, Democrats nominated Roosevelt to a third term—please do not tell Donald Trump.)

Of course, the days when party conventions delivered big surprises are over, or at least appear to be. This was another legacy of the 1968 convention, where delegates picked a nominee, Hubert Humphrey, who had not even competed in a single primary. To democratise the choosing of nominees, first the Democrats and then the Republicans took authority away from the conventions, with their smoke-filled rooms, and handed it to voters in primaries. As I wrote in January, the unintended consequence was to empower party activists, who tend to pick candidates who do not inspire a broad majority of Americans. Come to think of it, maybe 1968 is, unavoidably, the correct touchstone for this year’s contest.

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Blog Post1 week ago

Blog Post1 week ago

Economics5 days ago

Economics5 days ago

Economics1 week ago

Economics1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Personal Finance1 week ago

Economics6 days ago

Economics6 days ago

Accounting5 days ago

Accounting5 days ago

Personal Finance5 days ago

Personal Finance5 days ago